by Bruce Wells | Oct 26, 2013 | Petroleum Companies

Mrs. H. H. Honore Jr. of Chicago in 1915 was named president of a new petroleum exploration company led exclusively by women.

Although later derided for having “petticoat management,” a 1915 oil company run by women was part America’s growing suffrage movement. The Woman’s Federal Oil Company of America was a gender pioneer.

At the time, with nine out of 10 wells resulting in “dusters,” far more exploration companies failed than succeeded. Competition was fierce in the technical, speculative and very expensive search for new oilfields.

Most newly formed enterprises were run by men whose ambitions often exceeded their drilling experience and investment capital.

One gender exception was Mrs. H. H. Honore Jr. of Chicago. In 1915 she was named president of a new oil company led exclusively by women – five years before they were granted the right to vote for a U.S. president.

The Woman’s Federal Oil Company of America incorporated on November 22, 1915, in the District of Columbia with $750,000 capitalization. “Mrs. Honore was head of the company, which kept mere males out of the organization,” noted one reporter.

“The history of this woman’s oil corporation forms an intensely interesting story of the rare accomplishment of women, absolutely unaided by man,” gushed the reporter about the widow of prominent real estate businessman Harry H. Honore Jr.

“The reason men were kept out,” the reporter added, “is because ‘women are destined for equal leadership with men in the world of finance and promotion.'”

The company’s officers included, “some fifteen other equally well-known women, as executives and directors, (who) began the tremendous task of establishing a dividend-paying oil industry.”

More than 2,100 women bought shares in Woman’s Federal Oil and by 1917 it had acquired a charter to do business in Kansas.

Although the company acquired leases for 350,000 acres in Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas and Louisiana, Woman’s Federal Oil’s first two success wells came in Illinois.

In April and June of 1918, the company drilled near the town of East Oakland, Illinois. Both wells produced commercial amounts of natural gas. The company paid first dividends to stockholders the same year.

“It is no wonder that the entire financial world is doffing its hat to the Woman’s Federal Oil Company of America, and to the able women who manage it,” reported one industry trade journal. “This woman’s enterprise has made good.”

However, the next three exploratory wells drilled by Woman’s Federal Oil were expensive dry holes. Debts soon mounted and investors became wary. An article in a popular investment magazine did not help the company.

“Woman’s Federal Oil Company of America is purely a speculation and in our opinion, you would be better off to leave the stock alone,” declared editors of United States Investor magazine in January 1919.

The magazine frequently issued far harsher criticisms. In May 1919 it exposed the Prudential Oil and Refining Company as a stock scam run by notorious ad-man Seymour E. J. “Alphabet” Cox.

Petticoat Management

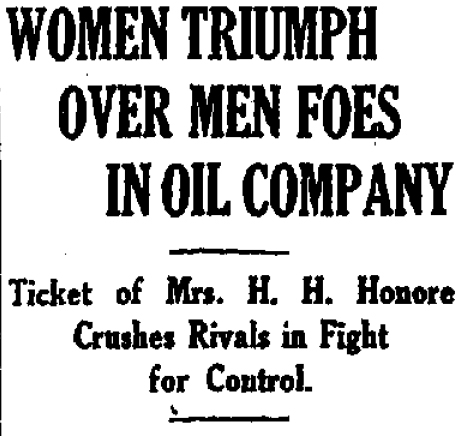

Meanwhile, Woman’s Federal Oil’s former company attorney, George Holmes, led a move against the board of directors to oust Mrs. Honore and her fellow female executives, whom he described as “petticoat management.”

“These women have no idea of the relation between income and disbursements,” proclaimed Holmes at a contentious meeting that included both sexes.

“Jeers, taunts, wild shouts prevailed through every minute of the session,” and the New York’s Syracuse Journal reported this exchange at the meeting:

The victory was short lived, although the company failed soon after men joined the board in 1920.

“I don’t think you’re much of an oil man, Mr. Ellis” interrupted Mrs. Honore. “And your statements are not true.”

“I don’t think you’re much of an oil woman, Mrs. Honore,” replied Ellis.

Mrs. Honore shattered her gavel.

“I am merely trying to get efficient management,” Holmes maintained. “I am prepared to go the limit, in court or out, to get this management, which the stockholders are entitled to,” Holmes said.

In the end, the attorney’s move to change board leadership failed.

“Women Triumph Over Men Foes In Oil Company,” exclaimed the Syracuse Journal headline when a final board vote retained Mrs. H. H. Honore Jr., as president. But the victory lasted only a year.

Despite some reported successful wells in Kansas oilfields, Woman’s Federal Oil’s fortunes continued to diminish. A January 12, 1920, meeting of stockholders in Chicago reviewed the company’s financial position. “The value of the 75,000 shares of stock, held mostly by women, deteriorated from $1,087,500 to $75,000,” noted one reporter.

“Amid heated argument five directors were elected. All were men. Mrs. H. H. Honore Jr….made no effort to retain her place on the board,” added a brief article headlined, “Woman’s Federal Oil Co. Has Merry Meeting.”

Mrs. Honore, who had resigned on December 31, 1919, was unavailable when creditors, including a bank in Independence, Kansas, announced the firm should be thrown into bankruptcy.

A newly formed H & H Oil Company of Kansas City prepared a stock exchange agreement to avert bankruptcy – but the best stockholders could hope for was receiving a fraction of their investment.

“Oil company which tabooed mere man, to pay 20-cents on dollar,” concluded a June 1920 newspaper. Although neither company survived, Woman’s Federal Oil stock certificates are valued by collectors.

The 19th Amendment to the Constitution, granting women the right to vote, was ratified on August 18, 1920. Mrs. Harriet Denham Honore, widow of Harry H. Honore Jr., died in New York City at 75 on July 18, 1938. “Although her marriage had united her to one of Chicago’s wealthy families, she had been reduced to the gifts of friends and a $20 a month old-age pension,” reported the New York Times.

___________________________________________________________________________________

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this AOGHS.ORG energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2018 Bruce A. Wells.

___________________________________________________________________________________

by Bruce Wells | Sep 24, 2013 | Petroleum Companies

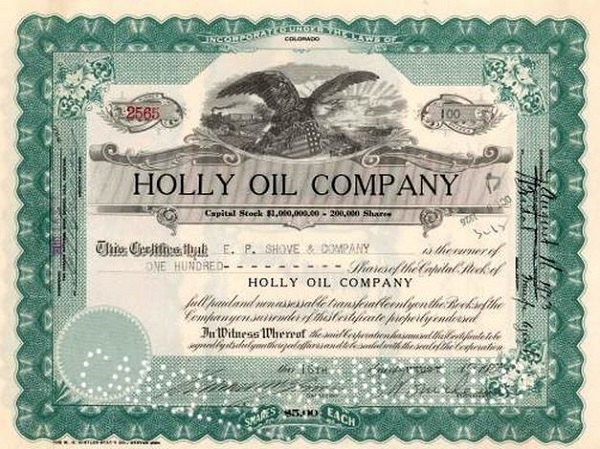

Although oil seeps along California’s coastline had drawn petroleum companies there as early as the 1890s, it would be decades before the rich pools were revealed. Stretching from Huntington Beach to north of Santa Barbara, several fields contained billions of barrels of oil.The Holly Oil Company was organized under the laws of Colorado, on June 14, 1921, to acquire and develop oil lands located in California’s Huntington Beach oilfield. It was a sugar company’s idea.

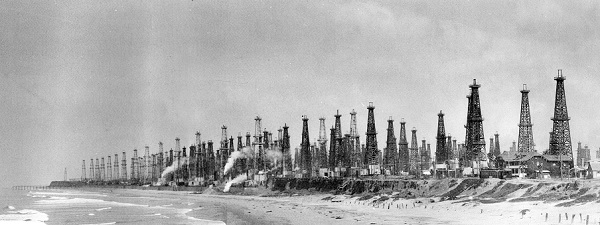

Huntington Beach’s growth began following a May 24,1920, discovery of the largest California oil deposit known at the time.

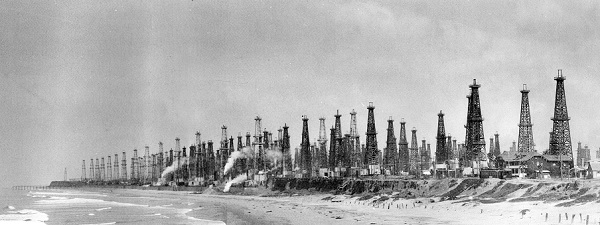

The Huntington Beach oilfield, circa 1926. Although still a productive oilfiled, less drilling by the early 1950s led to dismantling of derricks within the city and along the coast. Photo courtesy Orange County Archives.

Wells sprang up overnight and in less than a month the town grew from 1,500 to 5,000 people. A real estate boom brought thousands to the nearby community of Sunset Beach.

The city’s derricks were disappearing by the time the the last successful well was drilled in 1953 – the same year the city’s first surf shop, Gordie’s Surf Boards, opened.

Oil for Sugar Beets

At Huntington Beach, the Holly Sugar Company’s sugar beet refinery near the intersection of Gothard and Garfield streets had been there since 1911.

In order to devote the 14.7-acre property entirely to drilling for oil, the company disassembled its sugar beet refinery and shipped to Torrington, Wyoming, where it was rebuilt and operating by 1926.

Stockholders of Holly Sugar Company, founded in 1905 in Holly, Colorado, were given first preference to purchase shares of the new Holly Oil Company stock at $2 a share. It seems to have been a sweet deal.

The former sugar beet refinery property soon had 16 producing wells (including a 1,150 barrel a day well in 1922). Five railroad sidings were constructed to handle the 24-hour-a day-oil operations.

By 1923, daily oil production from Holly Oil wells reached 6,300 barrels. Records show the company was still actively drilling in the Huntington Beach oilfield in 1926, drilling the Conrad No. 1 well and the 1927 Huntington No. 2 well.

The California Department of Oil, Gas and Geothermal Resources’ last record of Holly Oil Company drilling was in 1940 when the company drilled and plugged the Meherin No. 1 well in San Luis Obispo County.

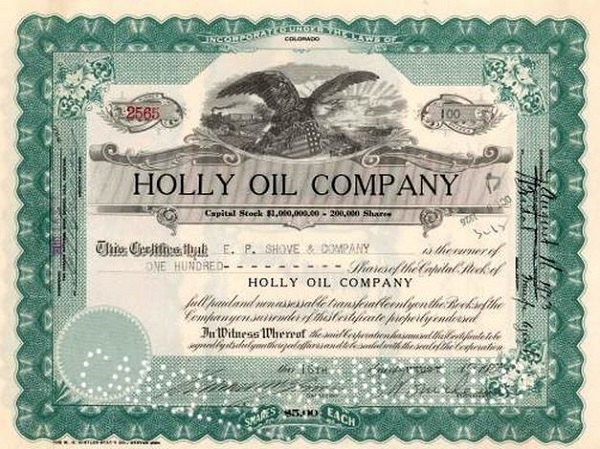

With its finely detailed vignette of an eagle with shield, Holly Oil Company stock certificates can be found online valued at about $50.

America’s offshore exploration industry began in the 1890s with drilling piers along the West Coast. Learn more California petroleum history in Discovering the Los Angeles Oilfield.

___________________________________________________________________________________

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this AOGHS.ORG energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2018 Bruce A. Wells.

by Bruce Wells | Sep 12, 2013 | Petroleum Companies

A 1957 oilfield discovery in Alaska Territory will helped establish 49th state.

Two years before Alaska statehood, Richfield Oil Corporation made an oil discovery that greatly benefited the exploration company (today’s ARCO) and the “north to the future” state.

Richfield Oil began in the petroleum business in 1915 as the Rio Grande Oil Company of El Paso, Texas. At the time, its main business was supplying U.S. military forces with gasoline in support of operations against Pancho Villa.

By 1936, Rio Grande had reorganized and merged with other companies to become Richfield Oil Corporation. Twenty years later, Richfield discovered an oilfield, that today is considered the state’s first commercial well (a 1902 well actually had revealed the Alaska Territory’s first commercial oilfield).

In July 1957, Richfield Oil’s Swanson River Unit No. 1 well, which produced 900 barrels of oil per day from a depth of 11,150 feet to 11,215 feet. The company had leased 71,680 acres of the Kenai National Moose Range, now the 1.92 million acre Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. More discoveries followed and by June 1962 about 50 wells are producing more than 20,000 barrels of oil per day.

Alaska’s oil production soon accounted for more than 90 percent of Alaska’s general fund revenues.

“The U.S. Congress viewed that discovery as the foundation for a secure economic base in Alaska, and statehood was granted two years later,” noted the Alaska Resources Council. A decade later, the discovery of the giant Prudhoe Bay oilfield on Alaska’s North Slope will make Alaska a world-class oil and natural gas producer – a status reaffirmed in 1969 with the discovery of the nearby Kuparuk field, the second largest in North America after Prudhoe Bay.

Four of the ten largest U.S. oilfields have been discovered on Alaska’s North Slope. In 1973, the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Authorization Act authorized construction of the 800-mile Trans-Alaska pipeline system from Prudhoe Bay to the port of Valdez.

Richfield Oil Corporation merged with the Atlantic Refining Company to form Atlantic Richfield Company in 1966. In 1999 BP Amoco purchased ARCO for $26.8 billion in stock, making BP Amoco the world’s second-largest petroleum company.

Regarding potential value of old Atlantic Richfield Corporation certificates, if the shareholder named on the certificate failed to surrender it during a change of ownership (merger, sale, etc.), the stock shares would have been cancelled on the books and any remaining value turned over to the Unclaimed Property Division of the owner’s state.

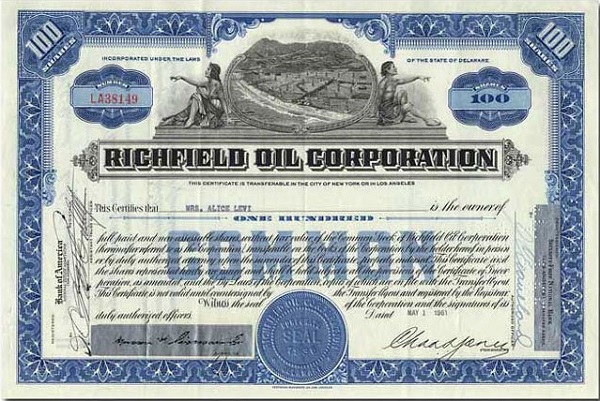

For more detailed company history, see From the Rio Grande to the Arctic: The Story of the Richfield Oil Corporation, authored in 1972 by former CEO Charles S. Jones. Obsolete Richfield Oil stock certificates are offered by collectors online for about $10.

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Support this energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2021 AOGHS. All rights reserved.