by Bruce Wells | Feb 6, 2017 | Petroleum Companies

Like many small oil exploration companies in the years before the Great Depression, Neilan Oil & Refining Company struggled to survive in highly competitive Texas oilfields. One of the company’s founders in 1922 was M.H. Gubbels of Houston, upon whose Fort Bend County land the new company’s first exploratory well would be drilled. Gubbels was joined by partners P.A. Neilan, J.J. Chadil, and C.H. Chernosky.

Capitalized with only $150,000, the company chose a drilling location south of Houston, two and one-half miles southeast of Thompson, and about a mile southeast of Smithers Lake. To protect Neilan Oil & Refining investment, drilling operations were conducted in virtual secrecy on the Marvel No. 1 well.

When the well reportedly “blew out at 3,833 feet” it had to be abandoned. Neilan Oil & Refining tried again less than yards 30 yards from the first site with the Marvel No. 2, “for the purpose of checking up on the lay of the cap rock.” Drilling reached 1,475 feet deep before being shut down.

In July 1922, Neilan Oil & Refining completed a well that produced natural gas. The Gubbels No. 1 well produced gas close to the two earlier test sites. “Until recently little was known relative to the identity of the company drilling these wells, and they were generally referred to as the ‘mystery wells,’ ” the Houston Post noted. It was even reported that “good gas sand was encountered at about forty feet.”

This unlikely shallow production “success” enabled further exploration; Neilan Oil & Refining extended operations 25 miles away to the area of Pliant Lake, Lockwood Mound, and Big Creek. But soon after another well, the Brown No. 1, began drilling, Neilan Oil & Refining virtualy disappeared from all accounts. The company reappeared two years later, brandishing a newly developing technology from Oklahoma that promised a great future.

“According to a current rumor, another salt dome has been found in the well of the Neilan Oil company,” reported the Houston Post reported in 1924. “It was located about three miles south of Orchard and about five miles west of Rosenberg.”

The newspaper account went on to describe a remarkable oil patch innovation (learn more in Exploring Seismic Waves). “Charges of dynamite were placed in the ground and exploded. The seismograph, which is an apparatus to register the shocks and undulatory motions of earthquakes, furnished data which indicated the presence of salt domes. After interpreting the data from the seismograph, the wells were drilled,” the article explained. It continued:

“In one case, the salt dome was found at a depth which varied only 30 feet from the instrument’s prediction. In both cases the lateral location of the domes, as given by the seismograph were correct Though the general principles Involved in the operation of the seismograph are known, the detailed mechanism of the instrument yet remains a mystery to all but a selected few in the oil industry. These few refuse to disclose the secret workings of a machine which has accurately pointed out the location of salt domes.

“Practically all oil found in coastal Texas has been found off the edge of salt domes. As used in the location of salt domes, the seismograph embodies the principles of the conventional instrument, but it also involves the use of a certain German patented improvement which makes the interpretation of impressions and sound waves more accurate…all interests using the seismograph in the United States and elsewhere have retained scientists trained in Germany to operate the instrument, it is understood. The two exception have trained men from their own geological departments for the work.”

But as with the latest innovations in oil field exploration technology, there are no guarantees in the high-risk, high-reward oil patch. What happened to Neilan Oil & Refining Company thereafter is hidden in U.S. petroleum history. Brief mention was last made in July 1929, just before the Great Depression.

___________________________________________________________________________________

The stories of exploration and production companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this AOGHS.ORG energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2018 Bruce A. Wells.

___________________________________________________________________________________

by Bruce Wells | Apr 14, 2016 | Petroleum Companies

Union Oil Company (Unocal, 1890-2005) drilled the “Chapman Gusher” in March of 1919 near Placentia, California. When completed, the well produced 8,000 barrels of oil a day, prompting a landslide of investors and speculators. The well was southeast of Los Angeles oilfields discovered in 1892.

Los Angeles businessmen organized the Richfield-Union Petroleum Company in October 1919 to join the fray. Extensively reported in the Los Angeles Herald, the Chapman Gusher opened the prolific Richfield-Placentia oilfield. The discovery well would continue producing for 70 years, but not all oil companies were so fortunate.

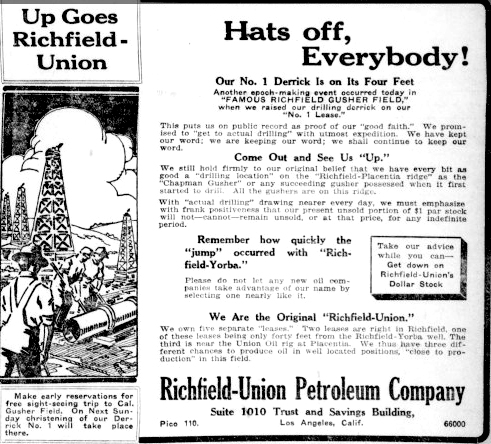

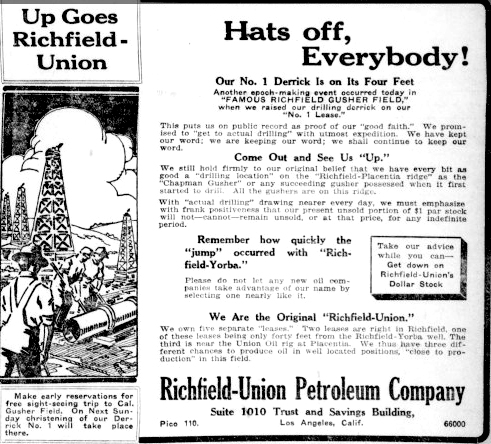

The July 1919 Mining and Oil Bulletin noted the “tremendous rush for oil lands, the paying of unheard of bonuses and royalties, and the tieing-up of all property for miles around.” Richfield-Union Petroleum managed to secure a 40-acre lease south of Placentia (Section 31, Township 3 South; Range 9 West) and began aggressive promoting stock sales to fund drilling.

The company offered an initial block of 50,000 shares of its stock for 50 cents per share in November 1919. Richfield-Union Petroleum was capitalized at $850,000 and raised the derrick for its first well within six months. It inticed investors with free sight-seeing trips and proclaimed, “You Should Buy Richfield-Union for its great speculative chances.”

The company offered an initial block of 50,000 shares of its stock for 50 cents per share in November 1919. Richfield-Union Petroleum was capitalized at $850,000 and raised the derrick for its first well within six months. It inticed investors with free sight-seeing trips and proclaimed, “You Should Buy Richfield-Union for its great speculative chances.”

However, relying on investor capital to sustain drilling operations made slow progress. New advertising offered company stock for $1 per share (or $1.03 “on time payments”) through the Los Angeles Stock Exchange. “Take our advice while you can – Get down on Richfield-Union’s Dollar Stock.”

By December 1920, the company’s first exploratory well was down to 2,150 feet, but “held up by a fishing job, the drill pipe having twisted off at 1,700 feet.” With dwindling finances, it took six more months to drill another 650 feet and still there was no oil.

The Los Angeles Herald of July 20, 1921, reported Richfield-Union’s properties were being taken over by the Comanche Oil & Refining Company, another Los Angeles venture. Comanche Oil & Refining subsequently reorganized as Comanche Oil Company with plans to drill more wells in the Richfield-Placentia field, but the California Department of Oil, Gas, and Geothermal Resources has no record of this.

Today, Richfield-Union Petroleum Company stock certificates survive as collectible reminders of an oil venture that failed. The first California oil well that launched the state’s petroleum industry was an 1876 gusher north of Los Angeles.

___________________________________________________________________________________

The stories of exploration and production companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this AOGHS.ORG energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2018 Bruce A. Wells.

___________________________________________________________________________________

by Bruce Wells | Sep 25, 2015 | Petroleum Companies

Fraudulent promotion of Alaska Dakota Development served an important purpose regarding the state’s oil industry

The 1957 discovery of the giant Swanson River oilfield on Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula excited interest from potential investors. As petroleum companies rushed to the new field, some shady promoters saw an opportunity.

By the end of the decade, New York Attorney General Carl Madonick noted that with securities fraud, the first big step was creation of a national market price via fictitious quotations and phony transactions.

Investors should be wary of shady promoters seeking to take advantage of the lure of “black gold.” Photo courtesy FBI.

Madonisk expained that such fictions helped to convince potential investors of a company’s legitimacy. He cited Alaska Dakota Development to illustrate such fraudulent schemes. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Mar 11, 2014 | Petroleum Companies

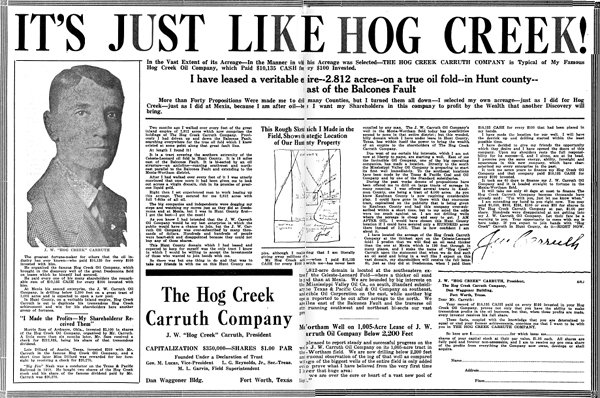

Exploring the companies and Ponzi schemes of a 1920s fake oilman.

Wherever men meet “to tell stories of great achievements of the gigantic industry, someone will always tell, amid a breathless silence, the amazing story of Hog Creek Carruth.”

He called himself J.W. “Hog Creek” Carruth. The investors he betrayed do doubt called him much worse. His “amazing story” began in a Texas boom town.

Hog Creek Carruth Oil Company was one of several Texas exploration companies created by Carruth, who gained his nickname after falsely claiming to have discovered the giant Desdemona oilfield at Hogg Creek.

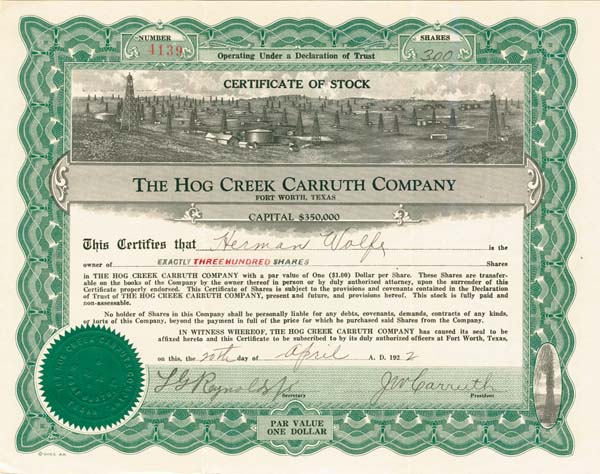

The Hog Creek Carruth Company was among several 1920s companies formed to take advantage of unwary investors seek petroleum wealth in Eastland County, Texas.

In fact, it was Tom Dees and the Hog Creek Oil Company that brought in Desdemona’s discovery well on September 2, 1918. The historic well blew in at 2,000 barrels of oil a day, delighting company investors, who reportedly profited more than $100 for every dollar they had invested. Carruth was among them.

“Hog Creek” Carruth, Stock Promoter

Located along Hog Creek and once called Hogtown, abundant oil production caused Desdemona to boom — and speculators to swarm. As it revelled in its newfound wealth, the town earned a nasty reputation. Texas Rangers had to intervene to keep order. Carruth’s relentless self-promotion and exuberant claims about the discovery soon earned him the “Hog Creek” Carruth moniker.

“The tiny peanut-farming hamlet of Desdemona in Eastland County was transformed when oil was struck in 1918,” notes the Texas State Library and Archives Commission. “Tents and shacks sprang up all around the town to house speculators and workers who flocked to the area, and the population grew from 340 to 16,000 almost overnight.”

Awash with prosperity, people and mud, by April 1920 the Texas Rangers had to be sent into Desdemona to keep order in the oil boomtown.

A contemporary account of the boom reported, “tales of Hogtown during the wicked oil days are too lurid for these pages, but we can say that its debauchery might be so well remembered because so much of it supposedly took place in broad daylight and sometimes not in private.”

Similar Texas drilling booms were taking place in Burkburnett along the Red River and in nearby Ranger, where the “Roaring Ranger” of October 1917 was Eastland County’s first gusher. Read more in Pump Jack Capital of Texas.

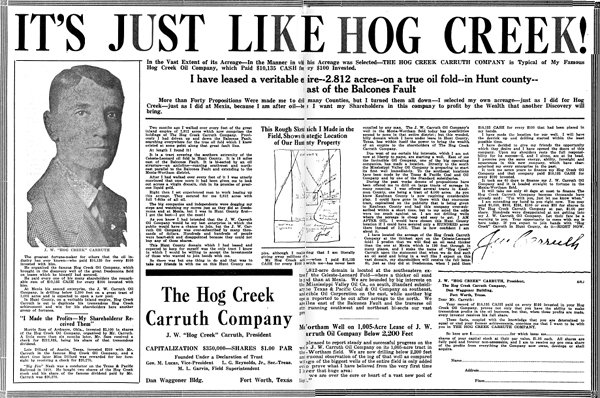

With speculators eager to profit from Desdemona, Carruth formed the J. W. Carruth Oil Company in 1919. Despite drilling several dry holes, he profited from selling his exuberantly advertised company stock.

However, just one year after its discovery, the Desdemona oilfield’s production would reach its peak of 7,375,825 barrels and then drop sharply, chiefly because of over drilling, according to the Texas State Historical Association.

Profiting from “Sucker Lists”

J.W. Carruth and his oil company prospered in 1919 by becoming a Ponzi scheme in which Carruth used naïve investors’ purchase money to pay dividends, thereby luring more buyers in a spiral which lined his pockets while emptying theirs. He personally profited by selling his buyers’ personal information.

“Sucker lists” with names, addresses and investment history of people who might buy oil shares had great value. The lists expanded during the multiple oil booms in Eastland County – and similar discoveries in Oklahoma, Kansas and California.

“Depending on the extent and quality of a list, its price ran from several hundred dollars to several thousand,” notes Roger Olien in his 1990 book, Easy Money: Oil Promoters And Investors In The Jazz Age. Predictably for Carruth Oil Company, litigation dogged “Hog Creek” Carruth.

Disputes over leasing and mineral rights continued for several years. He nonetheless sold about $600,000 worth of stock. After more dry holes and more stock sales, in January of 1922, Carruth even announced a new venture.

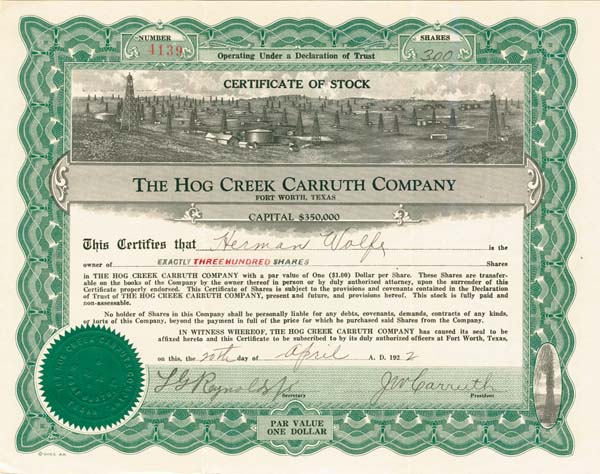

“I have called this company the Hog Creek Carruth Company, since it resembled so closely the famous Hog Creek Oil Company which I organized in 1917 and which in 1918 paid $10,135 cash dividends for every $100 that had been invested in it,” Carruth proclaimed.

Producing a blizzard of full-page promotions in newspapers from Ft. Worth to San Antonio and Port Arthur, the oil stock salesman finally ran afoul of “blue sky” laws, which sought to restrain such scams.

“The advertising of still another promoter, ‘Hog Creek’ Carruth of Fort Worth, Texas, caps the climax,” reported the Providence News on January 3, 1923.

“Modestly he admits that wherever men meet to ‘tell stories of great achievements of the gigantic industry, someone will always tell, amid a breathless silence, the amazing story of Hog Creek Carruth.’”

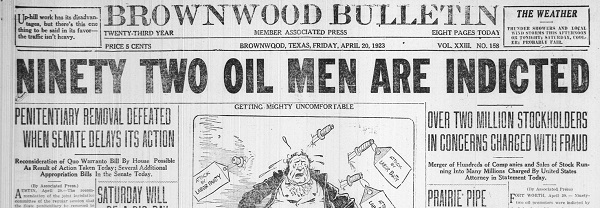

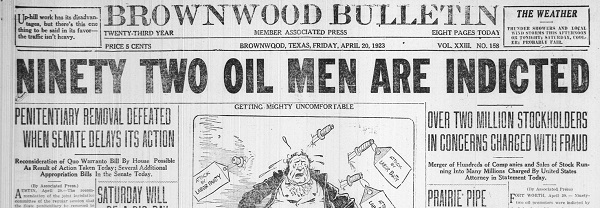

Indicted in 1923 along with 25 other Texas promoters for “fraudulent use of U.S. mails,” Carruth joined some nationally recognized swindlers.

Among those indicted were some of the most infamous stock promoters of the day: Dr. Frederick Cook, who had falsely claimed to have discovered the North Pole before Robert Perry, and the “genius of bunkum,” Seymour E. J. “Alphabet” Cox, the author of such enticements as, “Oil! Guaranteed Gushers! Five hundred percent, dividends. Pots of gold!”

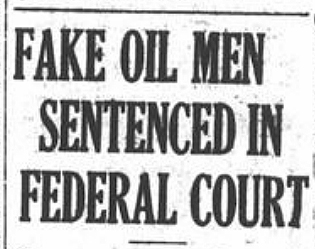

After testimony from almost 300 witnesses and a lengthy trial, Carruth, Cook, Cox and others were convicted of “dispersing stock-sales revenues as dividends, claiming income from non-producing wells, and otherwise misrepresenting the company’s position.”

After testimony from almost 300 witnesses and a lengthy trial, Carruth, Cook, Cox and others were convicted of “dispersing stock-sales revenues as dividends, claiming income from non-producing wells, and otherwise misrepresenting the company’s position.”

“Hog Creek” Carruth was sent to the Federal Penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas for a year. He died in obscurity in 1932.

“Hog Creek” Carruth was sent to the Federal Penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas for a year. He died in obscurity in 1932.

In 1934 the Securities and Exchange Commission was established to regulate the issue and sale of securities to protect the public from deceptive stock promotions. Also see the Spear Oil Company and Arctic Explorer turns Oil Promoter.

J.W. “Hog Creek” Carruth’s fraudulent oil ventures (also see Pilgrim Oil Company) have left behind stock certificates as family heirlooms that might some value for some financial certificate collectors. The history of more legitimate exploration companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Join today as an annual AOGHS annual supporting member. Help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2021 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Hog Creek Carruth Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/oil-riches-of-merriman-baptist-church. Last Updated: September 9, 2021. Original Published Date: March 11, 2018.

.

The company offered an initial block of 50,000 shares of its stock for 50 cents per share in November 1919. Richfield-Union Petroleum was capitalized at $850,000 and raised the derrick for its first well within six months. It inticed investors with free sight-seeing trips and proclaimed, “You Should Buy Richfield-Union for its great speculative chances.”

The company offered an initial block of 50,000 shares of its stock for 50 cents per share in November 1919. Richfield-Union Petroleum was capitalized at $850,000 and raised the derrick for its first well within six months. It inticed investors with free sight-seeing trips and proclaimed, “You Should Buy Richfield-Union for its great speculative chances.”

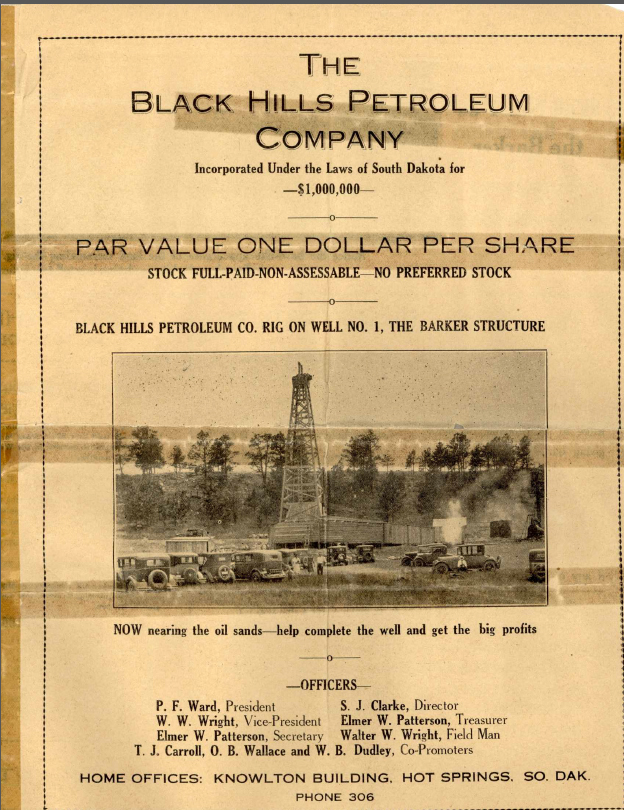

The first true oil production in South Dakota came in 1954 in northwestern corner of the state. Harding County wells produced oil from the massive Williston Basin.

The first true oil production in South Dakota came in 1954 in northwestern corner of the state. Harding County wells produced oil from the massive Williston Basin.

After testimony from almost 300 witnesses and a lengthy trial, Carruth, Cook, Cox and others were convicted of “dispersing stock-sales revenues as dividends, claiming income from non-producing wells, and otherwise misrepresenting the company’s position.”

After testimony from almost 300 witnesses and a lengthy trial, Carruth, Cook, Cox and others were convicted of “dispersing stock-sales revenues as dividends, claiming income from non-producing wells, and otherwise misrepresenting the company’s position.” “Hog Creek” Carruth was sent to the Federal Penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas for a year. He died in obscurity in 1932.

“Hog Creek” Carruth was sent to the Federal Penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas for a year. He died in obscurity in 1932.