by Bruce Wells | Dec 11, 2023 | Petroleum Companies

Texas Oil boom brings shady searchers for petroleum riches.

It was the greatest petroleum exploration and production since the birth of the U.S. oil industry in 1859. Hundreds of new companies formed in the wake of the spectacular 1901 “Lucas Gusher” at Spindletop Hill near Beaumont, Texas. Few had experience in the highly competitive and risky business of exploring for oil.

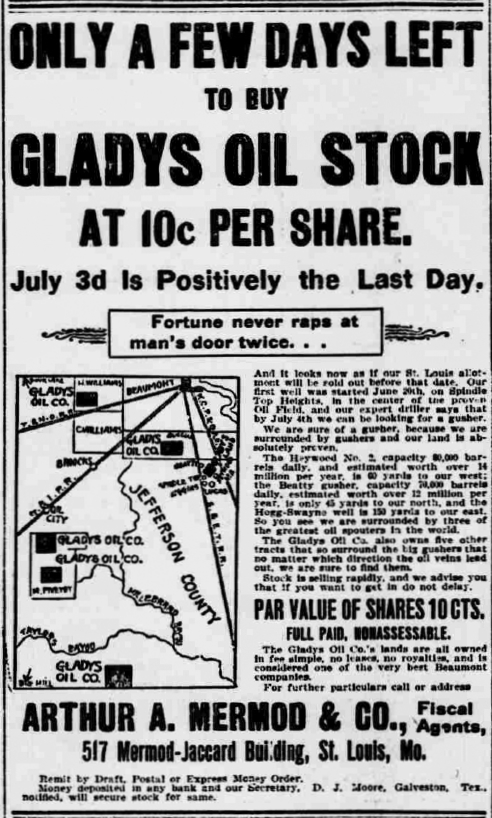

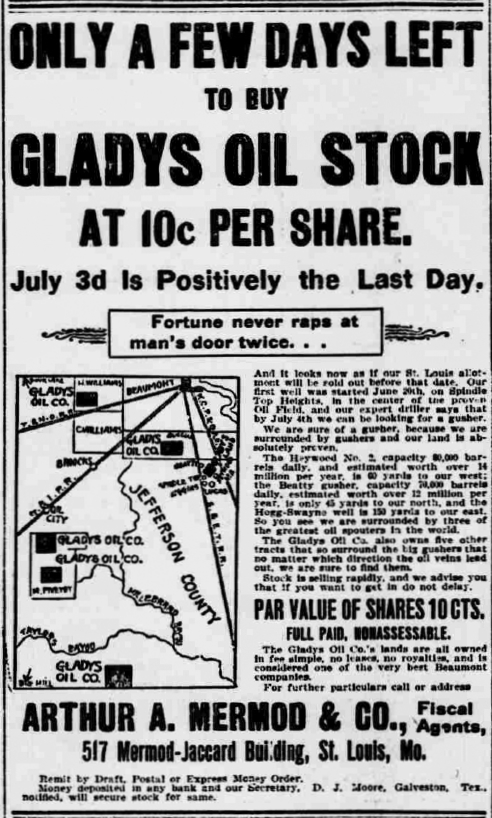

Among those ready to make fortunes for investors were two new “Gladys Oil” companies. One was from Beaumont, the other from Galveston. Contemporary maps show the Gladys Oil Company of Beaumont to have drilled a successful well very close to the famous January 10, 1901, “Lucas Gusher” well at Spindletop Hill that launched the modern U.S. petroleum industry.

Also in 1901, after 29 days of drilling in block 37, the company reported production from “Gusher No. 67” at a depth of 1,025 feet. Locating the “black gold” did not necessarily promise success.

“Swindletop”

By 1903 the Texas Secretary of State reported that Gladys Oil Company of Beaumont had “forfeited its right to do business in the state of Texas” due to a failure to pay franchise taxes. In a scenario that would repeat itself in other oilfields in coming decades, production from the giant field soon brought a collapse in oil prices.

By January 1902, stocks of both Gladys Oil companies were trading for less than 10 cents a share. The company was sued, lost, and United States Investor magazine reported it to be worthless two years later. Meanwhile, because some cash-strapped and desperate companies made questionable claims, newspapers began referring to the historic 1901 discovery as “Swindletop.”

In 1907, Success Magazine named the company in its “Fools and their Money” expose of fraudulent promotion schemes perpetrated by the New York, Chicago, and Beaumont Security Oil Trust. The Gladys Oil Company of Galveston lasted a little longer than its Beaumont twin, but not without controversy.

The trust had proclaimed, “it was impossible to lose” with an investment Gladys Oil Company of Galveston. In 1911 R.M. Smythe’s, Obsolete American Securities and Corporations, reported the stock to be worthless. Read about Pattillo Higgins, the man behind the great Spindletop discovery — and his Gladys City Oil, Gas & Manufacturing Company — see Prophet of Spindletop.

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS supporter and help maintain this website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Gladys Oil Company — Oil Shale Pioneer.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/gladys-oil-company. Last Updated: December 4, 2024. Original Published Date: September 11, 2013.

by Bruce Wells | Nov 13, 2023 | Petroleum Companies

“You will feel pretty good some of these fine mornings when your shares jump to 5 or 10 for one.”

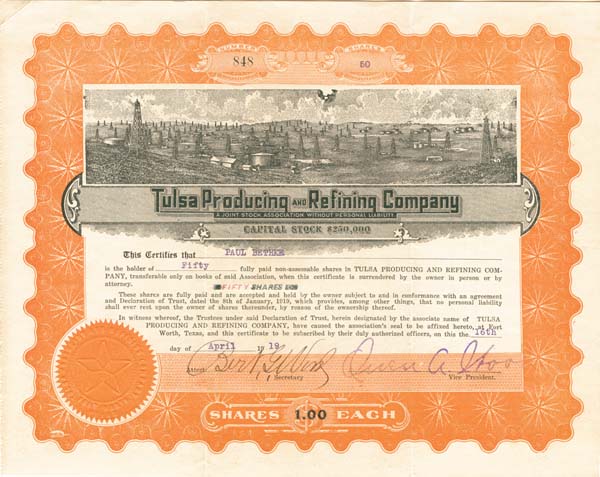

With oil booms in North Texas, especially along the Red River border with Oklahoma, Tulsa Producing and Refining Company incorporated to join the action in America’s growing Mid-Continent oil patch. In February 1919, the Texas El Paso Herald carried an advertisement for Tulsa Producing and Refining.

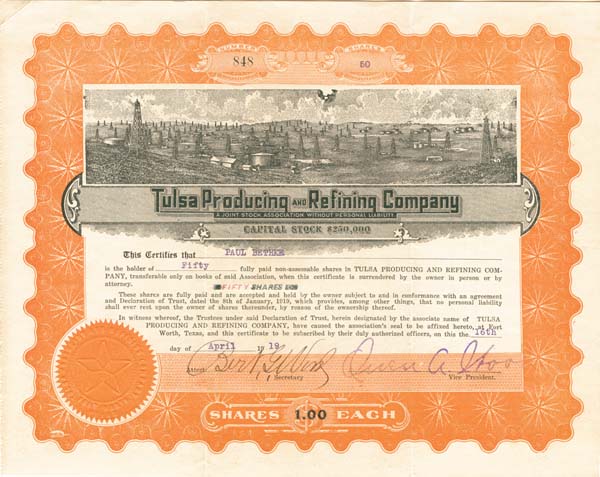

Stock certificate for the now defunct Tulsa Producing and Refining Company.

“A Strong, Solid Company With Two Wells Now Drilling” the advertisement proclaimed. It offered 250,000 shares of stock at $1 per share.

According to the company’s claims, the two wells were drilling in Comanche County, Texas, where Tulsa Producing and Refining reportedly held 1,000 acres under lease. Advertisements appeared in newspapers as far away as Pennsylvania, where America’s petroleum industry had begun in 1859 with the first U.S. oil well.

Frequent references were made to an oil boom in the remote region with 328,098 barrels of oil already produced. Even more enthusiastic advertisements about Texas discoveries followed in the Pittsburgh Gazette Times in May and June 1919.

“If either of these wells come in big, the shareholders of the Tulsa Producing & Refining Company will cash in strong – and do it quickly,” extolled perhaps one of the more conservative claims.

“You will feel pretty good some of these fine mornings when your shares jump to 5 or 10 for one,” added the company. “We believe this is going to happen – and happen soon, too.”

The predicted happiness apparently didn’t happen. All references to the company disappear thereafter.

Popular Certificate Vignette

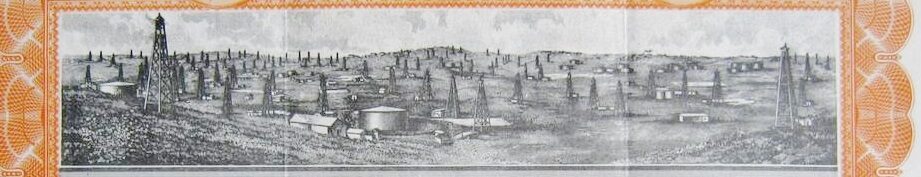

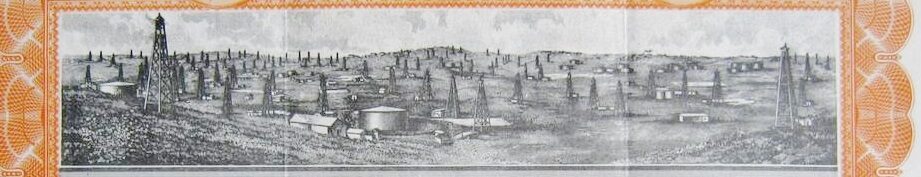

Seeking investors to chase “black gold” riches led to a surge in printing scenes of derricks on stock certificates.

Drilling booms often lead to many quickly formed (and quickly failed) exploration companies. As company executives rushed to print stock certificates, they often chose this same scene of derricks and oil tanks.

In the rush to promote their drilling plans, new companies had little time or money to find original art. One oilfield vignette from print shops proved particularly popular.

Among the most often used scenes was of a panorama of derricks found on certificates issued by the Double Standard Oil & Gas Company, the Evangeline Oil Company, the Buffalo-Texas Oil Company, and many other oil exploration ventures.

More articles about the attempts to join exploration booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an the updated research at Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The fire in the rock: A history of the oil and gas industry in Kansas, 1855-1976 (1976); Chronicles of an Oil Boom: Unlocking the Permian Basin

(1976); Chronicles of an Oil Boom: Unlocking the Permian Basin (2014). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2014). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2023 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Tulsa Oil and Refining Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL:https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/tulsa-producing-and-refining-company. Last Updated: November 14, 2023. Original Published Date: April 2, 2015.

by Bruce Wells | Aug 2, 2022 | Petroleum Companies

Oil stock certificate from 1901 helps tell story of the Boulder oilfield and early Colorado discoveries.

Colorado oil history revealed from researching an old oil company stock certificate.

Dated March 1902, a stock certificate had been issued by a Wyoming venture — the Savannah Oil, Coal and Gas Company. The company president’s signature was too hard to make out, according to the guest post on the the American Oil and Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) Stock Certificate Q & A Forum — a popular section of Is My Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

The poster added: “I would appreciate any information available on this company. Researching for my 90-year-old Mom!” Like many others, the visitor to AOGHS website sought information about his family’s stock certificate.

Drilling for natural gas in 2005 in the Denver Basin’s Wattenberg gas field, discovered in 1970. Photo courtesy geologist and engineer Dan Plazak.

The story of Savannah Oil, Coal and Gas began just before its incorporation — when a headline-making oilfield discovery at Boulder, Colorado, inspired the founding of many exploration companies. Most of these ventures would not survive.

According to a 1902 biennial report from the Colorado Secretary of State, Savannah Oil, Coal and Gas Company had a principal office in Cheyenne, Wyoming, for doing business in Colorado. The also report listed a T.F. Little as a sales agent with Boulder as a place of business.

Boulder Oilfield

Natural oil seeps first drew “bobbers” to the Boulder area, according to a 1905 Colorado Geological Survey report.

“The principle on which the use of a bobber rests is the same as that by which the proper site of a water well is determined by the involuntary turning of a witch-hazel sprout when held in the hand,” the survey noted.

In the Boulder field, bobbers fixed “the exact location off a large proportion of the wells, the geological survey added. One such oil well was on the McKenzie farm, about three miles northeast of town. It was the discovery well that opened the Boulder oilfield — the first of many in the Denver Basin.

The McKenzie well that launched drilling in Boulder field would pump oil until 2007.

Initially producing 70 barrels of oil a day, the 1901 McKenzie well spawned a scramble for nearby mineral leases as the local newspaper, The Daily Camera, reported a thousand companies formed in three months. Savannah Oil, Coal, and Gas Company was among them.

Despite the disdain of petroleum geologists, modern bobbers and other dowsing tools are available from the American Society of Dowsers (ASD), established in 1961. For attempts of finding Texas oilfields using psychic readings, see Luling Oil Museum and Crudoleum.

Savannah Oil, Coal, and Gas

Savannah Oil, Coal, and Gas incorporated on February 11, 1902, with C.B. Younglove as president and its principal agent in Boulder. The vice president was T.F. Little.

Capitalized at only $15,000 with its main office in Cheyenne, Wyoming, the company needed early success in the Boulder oilfield to survive. When Younglove learned the Otero Company had drilled and completed producing oil wells northeast of Boulder, he managed to secure leases close by.

Savannah Oil, Coal, and Gas Company would drill in Boulder County’s Section 8 and Section 9, Township 1 North, Range 70 West (Public Land Survey System – PLLS). Today, the well sites are near the intersection of Valhalla Drive and Kelso Road.

By late 1902, a business journal reported Savannah Oil, Coal, and Gas drilling for oil in the Boulder field.

“T.F. Little, the vice president says they have one well 2,600 feet deep with about 1,000 feet of oil in it, and have recently moved derrick to land adjoining the Otero well (which is now producing about 100 barrels per day), and the run hole is now about 300 feet deep, just over the fence from the Otero property,” noted the American Investor, adding Vice President Little, “also says they are not now offering any stock for sale.”

By 1905, the U. S. Geological Survey (Bulletin No. 265) published more detail on the Younglove and Savannah producing oil wells, depths, unsuccessful attempts or “dry holes,” and use of nitroglycerin for fracturing oil-producing geologic formations (learn more in Shooters – A Fracking History).

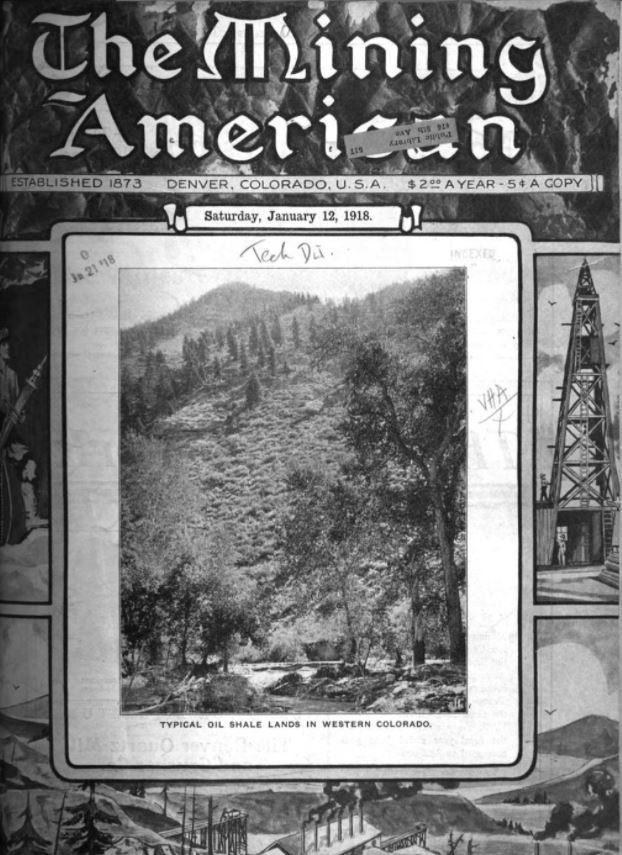

Citing earlier wells drilled by the Savannah Oil, Coal, and Gas Company, Mining American magazine in 1918 noted, “Possibilities of Greater Production in Boulder Oil Fields,”

The first three wells of Savannah Oil, Coal, and Gas produced enough oil to support more drilling in the booming Boulder field. After production peaked in 1909 at more about 85,000 barrels of oil, some people would claim Boulder made Colorado oil history as, “one of the wildest, crookedest, and most disastrous booms.”

Local historian Silvia Pettem summarized, “Although the oil under the land northeast of Boulder was real, no amount of drilling could keep up with inflated expectations. In just a few months, the bottom fell out of the market.”

Although C.B. Younglove and T.F. Little’s Savannah Oil, Coal, and Gas Company would fade away, by World War I, Mining American magazine teased speculative investors with “Possibilities of Greater Production in Boulder Oil Fields” (January 5, 1918), citing the exploratory wells of Savannah Oil, Coal, and Gas. The magazine proclaimed, “Recent Survey Encourages Deeper Drilling…Younglove Well Commended by Expert.”

But the Boulder boom was already part of U.S. petroleum history. So was Savannah Oil, Coal, and Gas Company.

First Colorado Oil Well

The first commercially successful Colorado oil well was drilled in January 1862 near the mining supply town of Cañon City, about 45 miles southwest of Colorado Springs. The well produced oil just three years after the first U.S. oil well, which was drilled in Titusville, Pennsylvania, by Edwin L. Drake for the Seneca Oil Company of New Haven, Connecticut.

In 1860, businessman Gabriel Bowen had established what many consider Colorado’s first oil venture, the G. Bowen & Company. Bowen claimed ownership of natural oil seeps at Oil Spring — above what would later prove to be the Florence oilfield.

However, Bowen’s claim, “apparently was jumped in the winter of 1860-61 by J.L. Dunn, who dug four pits at the spring,” according to Colorado Encyclopedia. “One of the pits produced a barrel per day, but the others yielded little. Dunn left the area in early 1861, after being charged with cattle rustling.”

Although Bowen regained control of Oil Spring, Alexander Cassidy bought the claim in January 1862 and formed the Colorado Oil Company, “the state’s first commercially productive oil enterprise,” the encyclopedia noted in 2021. Cassidy’s well produced “at most a few barrels per day, which the company sold in Cañon City, Denver, and Santa Fe.”

With wells reaching a depth of 1,445 feet by the 1890s, production in Colorado’s Florence oilfield would peak at more than 3,000 barrels of oil per day.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Geology of the Boulder district, Colorado: USGS Bulletin 265 (2013); High Altitude Energy: A History of Fossil Fuels in Colorado (2002). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Join today as an AOGHS annual supporting member. Help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2023 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Exploring Boulder Oilfield History.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/oil-riches-of-merriman-baptist-church. Last Updated: August 6, 2022. Original Published Date: August 24, 2021, 2021.

by Bruce Wells | Apr 14, 2018 | Petroleum Companies

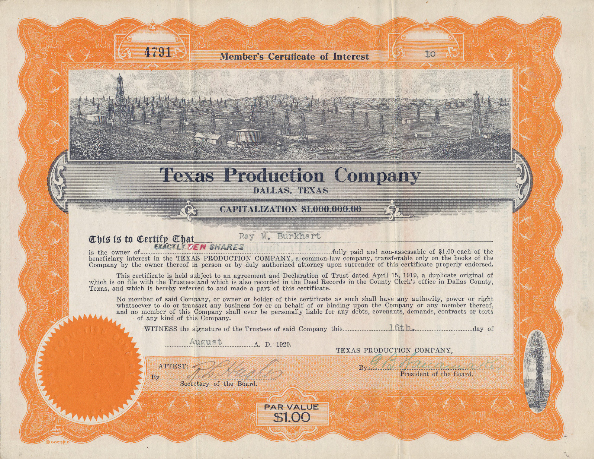

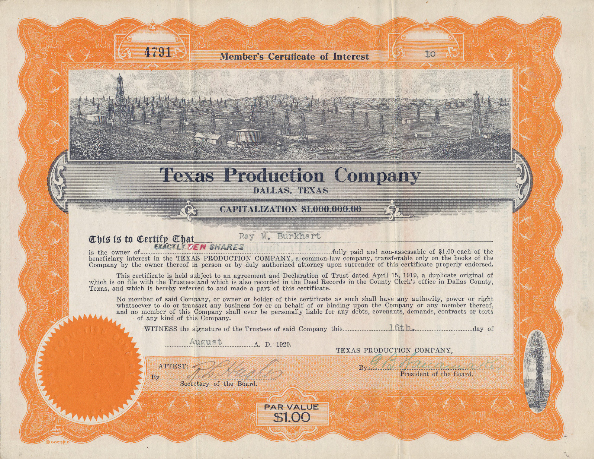

Texas Production Company was incorporated on June 18, 1917, with $1 million in capital. It would find oil in booming North Texas oilfields – but not survive the competition.

Texas Production Company was incorporated on June 18, 1917, with $1 million in capital. It would find oil in booming North Texas oilfields – but not survive the competition.

By 1919, Texas Production completed the Renner No. 1 well at 475 barrels of oil a day from the Waggoner oilfield, near Electra and the recent extension of the Burkburnett field (Electra would someday be declared the Pump Jack Capital of Texas).

According to the Texas Historical Commission, exploration and production in this area was minimal until April 17, 1919, when the Bob Waggoner Well No. 1 blew in producing an astounding 4,800 barrels of oil per day. It was the first well in what became known as the Northwest Extension Oilfield, comprised of approximately 27 square miles.

Oil had been found in 1912 west of Burkburnett in Wichita County, followed by another oilfield in the town itself in 1918. The Wichita Falls region’s drilling booms inspired a 1940 Academy award-winning movie. Learn more Boom Town Burkburnett.

The company also appears to have drilled productive oil wells in the in the Humble oilfield of Harris County, bringing in the Bissonnet No. 1 well to a depth of over 4,000 feet, one of the deepest – and one of the most expensive – in the field at the time.

Although that well reportedly produced up to 2,000 barrels of oil a day in 1921, competition for leases and equipment intensified amid falling oil prices. In the same year, a Texas Production Company investor sought advice from a leading financial publication. The answer was not promising.

“So far as we can make out you bought into an oil production of little or no merit, which has simply gone the way of any number of such enterprises,” United States Investor noted.

“Shares of the Texas Production Company are now being offered at a few cents a share by unlisted brokers which would indicate that a sale of your stock would net you little,” the magazine added. “There is no way for you to get your money back.”

United States Investor encouraged its readers to avoid investing in any questionable petroleum-related bonds. “This may be a time for strong companies to invest in oil at a low figure,” Investor proclaimed, “but a company which must bond itself to pull itself out of a hole can’t do much in the way of speculation on the future price of oil to get back for its stockholders what has been already taken by unscrupulous promoters.”

Texas Production Company’s stock certificate includes the same vignette of derricks seen on those of other companies quickly formed in booming oil regions, including Centralized Oil & Gas Company, the Double Standard Oil & Gas Company, the Evangeline Oil Company, and the Tulsa Producing and Refining Company.

___________________________________________________________________________________

The stories of many exploration companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society welcomes sponsors to help preserve petroleum history. Please support this energy education website with a contribution today. Contact bawells@aoghs.org for membership information. © 2019 AOGHS.