Rocky Beginnings of Petroleum Geology

Petroleum pioneers who took earth science to a deeper level.

When oil burst onto the U.S. marketplace as a commercial opportunity for refining into kerosene lamp fuel, the art and science of petroleum geology was born.

The coal-mining industry had long provided employment for geologists and the oil boom presented a new kind of mineral wealth for America and a new challenge for geologists. But Pennsylvania’s first oil exploration ventures soon found that hiring geologists didn’t significantly improve their chances of success in an already risky business.

Henry D. Rogers, (1808 – 1866) was one of the first professional U.S. geologists.

Decades before the Civil War, the pursuit and mining of coal prompted many geological surveys, studies, and assessments of potential mineral resources. Railroads stretching westward needed good quality coal supplies and routes always considered the availability of nearby sources.

Oil Seeps and Salt Wells

Searching for high-quality bituminous coal in America, many early geologists had reported oil seeps and the associated landforms, but mostly as a curiosity and in relation to their proximity to coal beds. In Kentucky, Ohio, and the western part of what is now West Virginia, the salt business also gave important insights into formations called “structural traps.”

Drilling commercial brine wells and salt manufacturing was a lucrative industry. Geologists’ surveys found that strata of sedimentary rock fractured, faulted, and folded, sometimes producing salt domes and brine deposits.

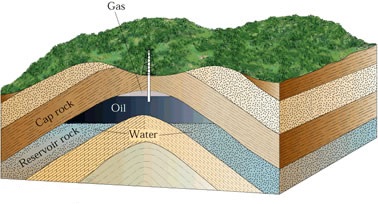

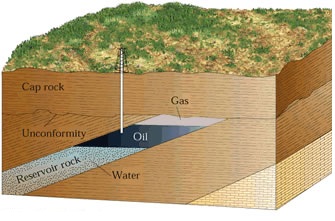

Geologists also noted that oil and natural gas was occasionally trapped in porous deposits sandwiched between impermeable rock layers. Such contamination fouled commercial brine wells and was an unwelcome intrusion, but cottage industry entrepreneurs skimmed it off and sold it for patent medicine, lubrication, and other novel purposes.

In Kentucky, Ohio and West Virginia, geologists studied landforms associated with salt brine and coal “structural traps.” These anticlinal traps held oil and natural gas because the earth had been bent, deformed or fractured. Unsuccessfully applying structural trap theories to Pennsylvania’s differing geology undermined early petroleum geologists’ credibility.

A pioneering Ohio physician and natural scientist named Samuel Hildreth examined and recorded details of the salt business in southeastern Ohio, noting structural traps as a geologic feature associated with brine, coal, and oil.

In 1836, Hildreth published his extensive “Observations on the Bituminous Coal Deposit for the Valley of the Ohio, and the Accompanying Rock Strata.” It was America’s first petroleum geology primer.

Hildreth was a strong advocate for Ohio’s first geological survey and later served as the state geologist. His observations of the structural trapping of petroleum were later affirmed by Pennsylvania’s state geologist, Henry D. Rogers, who erroneously declared that Pennsylvania’s oilfields were likewise based on structural trapping of petroleum in anticline formations.

Pennsylvania’s oilfields were in fact found predominantly in another kind of formation altogether, the “sandstone stratigraphic trap,” but Rogers’ prestigious endorsement, circulated widely in an 1863 Harper’s Magazine article, convinced geologists to the contrary.

The search for oil prompted the first petroleum geologists to impose Hildreth and Rogers’ structural trapping theory on Pennsylvania’s differing geology. It didn’t work and their failures in Pennsylvania hindered the acceptance of petroleum geologists for decades.

Although structural trapping remains a dominant characteristic for many of America’s most prolific oil and natural gas fields, ironically it wasn’t so in Pennsylvania’s Oil Creek region, where the petroleum industry was born. As noted by author and geologist Ray Sorenson, “theories of trapping did not work in the absence of anticlines.”

Sorenson, who has researched first documented reports of oil worldwide (see Earliest Signs of Oil), also reported the science of petroleum geology took some time to develop — and be accepted.

The dominant oil bearing feature in Pennsylvania’s oil region is a sedimentary geologic formation known as a “stratigraphic trap” and differs significantly from a structural trap. It is formed in place by erosion, usually in porous sandstone enclosed in shale. The impermeable shale keeps the oil and gas from escaping.

It took until the turn of the century before successful geologically driven discoveries in the Mid-Continent and Gulf regions encouraged exploration companies to use petroleum geologists.

Although the science of geology had revealed the 34-square-mile El Dorado oilfield in central Kansas in 1915, many companies still had little confidence in geologists.

James C. Donnell, president of the Ohio Oil Company (later Marathon Oil) proclaimed, “The day The Ohio has to rely on geologists, I’ll get into another line of work.”

But after the company’s first geologist, C.J. “Charlie” Hares found 19 oil and natural gas fields, Donnell changed his mind and declared Hares to be “the greatest geologist in the world.”

AAPG inspires professional conduct amongst its more than 30,000 members.

Increasing understanding and acceptance of petroleum geology as a valued tool in exploration led to the 1917 formation of the Southwestern Association of Petroleum Geologists, precursor to today’s American Association of Petroleum Geologists. Since then, AAPG has fostered scientific research, advanced the science of geology, and promoted new technologies.

Father of American Geology

Born in Ayr, Scotland, William Maclure (1863-1840) created the earliest geological maps of North America, becoming a renowned American geologist and “stratigrapher.” Many geologists consider Maclure the Father of American Geology.

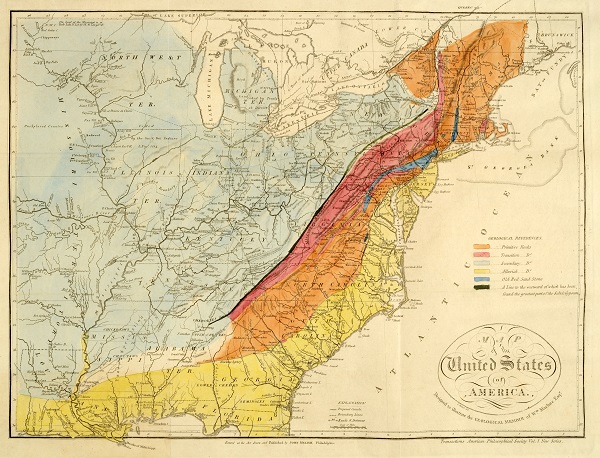

“Map of the United States of America, Designed to Illustrate the Geological Memoir of Wm. Maclure, Esqr.” This 1818 version is more detailed than the first geological map he published in 1809. Image courtesy the Historic Maps Collection, Princeton Library.

Maclure settled in the United States in 1797, and by 1808 he had traveled from Maine to Georgia to produce the first U.S. geological map, published in the Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. “Here, in broad strokes, he identifies six different geological classes,” a Princeton geologist later reported. “Note that the chain of the Appalachian Mountains is correctly labeled as containing the most primitive, or oldest, rock.”

When Yale chemist Benjamin Silliman organized the American Geological Society in 1819, Maclure was elected its first president. In the 1850s, Silliman’s son, also a Yale chemist, analyzed samples of Pennsylvania “rock oil” for refining into kerosene. His report led to drilling America’s first oil well in 1859.

Father of Petroleum Engineering

John Franklin Carll, a geologist born in Bushwick, New York, on May 7, 1828, could be considered the world’s first petroleum engineer. He developed many of the exploration and production industry’s geological methods — and helped pioneering oil driller Lyne Taliaferro Barret drill the first Texas oil well.

“In 1875, Carll published strip logs from nine Pennsylvania wells, and he used them for correlation purposes in much the same manner as they are employed today,” noted the Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE). “His work also confirmed the theory that oil sands lie in lens-shaped masses, not in continuous belts, and that oil does not occur in underground pools or lakes, but in pores of sandstone.”

“More than a century ago, he expressed the principles of petroleum engineering and geology that established much of the framework for the development of petroleum engineering technology,” proclaimed SPE, which established the John Franklin Carll Award in 1958.

The earth sciences of petroleum geology and engineering have come a long way since pioneering steps and stumbles in the Ohio River Valley and Pennsylvania’s early oilfields. Modern geologists grapple with vast amounts of data and technological innovations in pursuit of petroleum.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1936); Anomalies, Pioneering Women in Petroleum Geology, 1917-2017 (2017); The Natural Gas Industry in Appalachia (2005); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an annual AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2022 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Rocky Beginnings of Petroleum Geology.” Authors: B.W. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/technology/petroleum-geologys-rocky-beginnings. Last Updated: October 24, 2022. Original Published Date: February 14, 2016.