Secret History of Drill Ship Glomar Explorer

Offshore technologies advanced after Howard Hughes and CIA raised a lost Soviet submarine in 1970s.

Launched in 1972, the Glomar Explorer left behind two remarkable offshore exploration histories: a clandestine submarine recovery vessel and the world’s most advanced deep-water drill ship. The CIA’s former “ocean mining” ship ended a pioneering offshore petroleum career in 2015 at a Chinese scrapyard.

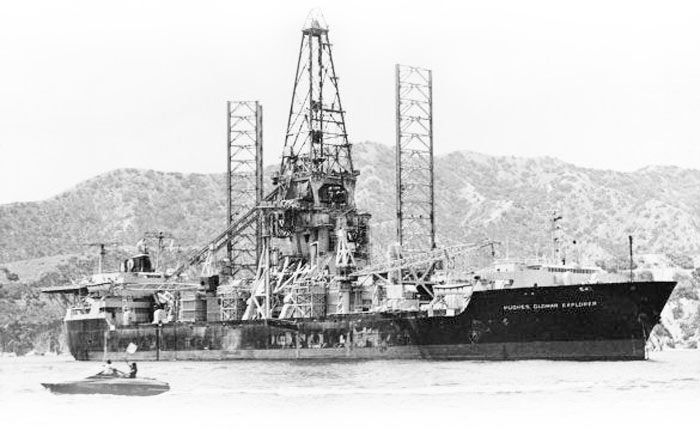

Considered a pioneer of modern drill ships, the Glomar Explorer was decades ahead of its time, working at extreme depths for the U.S. offshore petroleum industry. Relaunched in 1998 as an offshore technological phenomenon, the original Glomar Explorer had been constructed as a top-secret project of the Central Intelligence Agency.

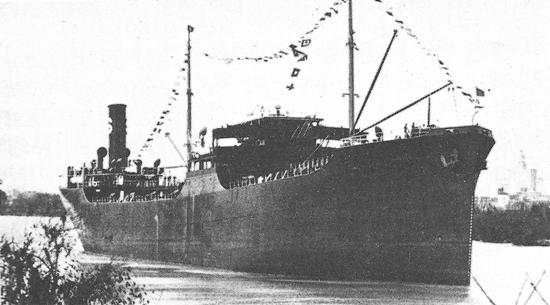

Hughes Glomar Explorer, a custom-built “magnesium mining vessel” for the CIA that in 1974 recovered part of a Soviet submarine off Hawaii. Photo courtesy American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

CIA Project Azorian began soon after the U.S.S.R. ballistic missile submarine K-129 mysteriously sank somewhere in the deep Pacific Ocean northeast of Hawaii on March 8, 1968. The wreckage of the lost sub could never be found — or so it seemed.

Unknown to the Soviets, sophisticated U.S. Navy sonar technology would locate the K-129 on the seabed at a depth of 16,500 feet. But a salvage operation more than three miles deep was impossible with any known technology (see ROV – Swimming Socket Wrench).

The K-129 sinking presented the CIA with such an espionage opportunity that the agency convinced President Richard Nixon to approve a secret operation to attempt raising the vessel from the ocean floor.

Secretive billionaire Howard Hughes Jr. of Hughes Tool Company joined the mission, code-named Project Azorian (mistakenly called Project Jennifer in news media accounts).

The recovery effort would involve years of deception: deep ocean mining would be the cover story for construction of the Hughes Glomar Explorer.

Hughes “Ocean Mining”

Scientists and venture capitalists had long seen potential in ocean mining, but when Hughes appeared to take on the challenge, the world took notice. The well-publicized plan described harvesting magnesium nodules from record depths with a custom-built ship that would push engineering technology to new limits, typical of Hughes’ style. The story spread.

But from concept to launch, the Hughes Glomar Explorer had one purpose: Raise the sunken Soviet Golf-II class submarine from 1968 — and any ballistic missiles. Construction began in 1972 by Sun Shipbuilding and Drydock Company in a Delaware River facility south of Philadelphia. Hughes’ $350 million (about $261 billion in 2024) high-tech ship was ostensibly built to mine the sea floor.

On August 8, 1974, the “magnesium mining vessel” secretly raised part of the 2,000-ton K-129 through a hidden well opening in the hull and a “claw” of mechanically articulated fingers that used seawater as a hydraulic fluid. News about Project Azorian leaked within six months.

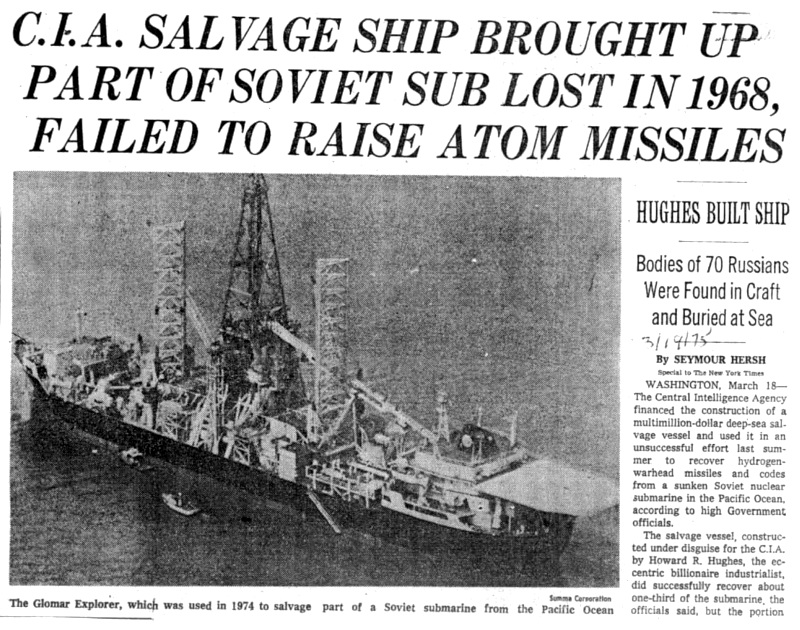

Seymour Hersh of the Los Angeles Times revealed the clandestine project on February 7, 1974. An investigative reporter, he had won the Pulitzer Prize in 1970 for exposing the My Lai massacre.

On February 7, 1974, the Los Angeles Times broke the story: “CIA Salvage Ship Brought Up Part Of Soviet Sub Lost In 1968, Failed To Raise Atom Missiles.”

The L.A. Times article by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Seymour Hersh ended the high-tech vessel’s spying career. The government transferred the Hughes Glomar Explorer to the Navy in 1976 for an extensive $2 million preparation for storage in dry dock. With its CIA days over, the vessel spent almost two decades mothballed at Suisun Bay, California.

Pioneer Drill Ship

London-based Global Marine had converted the CIA vessel for commercial use. The company hired Electronic Power Design of Houston, Texas, to work on the advanced electrical system. After almost 20 years in storage, the condition of equipment inside the ship surprised Electronic Power Design CEO John Janik.

“Everything was just as the CIA had left it,” Janik explained, “down to the bowls on the counter and the knives hanging in the kitchen. Even though all the systems were intact, this was by no means an ordinary ship.”

Janik noted in 2015 for The Maritime Executive that his company’s retrofit was “a tough job because the ship’s wiring was unlike anything we had ever seen before,” although preservation had been helped by nitrogen pumped into the ship’s interior for two decades.

Conversion work later included a Mobile, Alabama, shipyard adding a derrick, drilling equipment, and 11 positioning thrusters capable of a combined 35,200 horsepower. Completed in 1998 as the world’s largest drillship, Glomar Explorer began a long-term lease from the U.S. Navy to Global Marine Drilling for $1 million per year.

The advanced drilling ship spent the next 17 years working in deep-water sites around the globe, including Africa’s Nigerian delta, the Black Sea, offshore Angola, Indonesia, Malta, Singapore, and Malaysia.

Following a series of corporate mergers, Glomar Explorer became part of the largest offshore drilling contractor, the Swiss company Transocean Ltd. When it entered that company’s fleet, the ship was renamed GSF Explorer and in 2013 was re-flagged from Houston to the South Pacific’s Port Vila in Vanuatu.

The former top-secret CIA vessel Glomar Explorer began a record-setting career in 1998 as a technologically advanced deep-water drill ship. Photo courtesy American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

When GSF Explorer arrived at the Chinese shipbreaker’s yard in 2015, many offshore industry trade publications took notice of the ship’s demise after years of exceptional deep drilling service. The ship was “decades ahead of its time and the pioneer of all modern drill ships,” declared the Electronic Power Design CEO in The Maritime Executive article.

“It broke all the records for working at unimaginable depths and should be remembered as a technological phenomenon,” Janik concluded.

Soon after the former Glomar Explorer was sold for scrap, Tom Speight of the engineering firm O’Reilly, Talbot & Okun, reflected in a company post, “This is a shame, not only because of the ship’s nearly unbelievable history, but also because in 2006 the American Society of Mechanical Engineers designated this technologically remarkable ship a historic mechanical engineering landmark.”

The ASME award ceremony, which took place on July 20, 2006, in Houston, included members of the original engineering team and ship’s crew among the attendees. Past President Keith Thayer noted the important contributions the ship made to the development of mechanical engineering and innovations in offshore drilling technology.

The historic ship’s name will forever be linked to the ship’s CIA clandestine service during the Cold War. For many veteran journalists, the agency’s chronic response to inquiries, “We can neither confirm nor deny,” is still known as the “Glomar response.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The CIA’s Greatest Covert Operation: Inside the Daring Mission to Recover a Nuclear-Armed Soviet Sub (2012); Project Azorian: The CIA and the Raising of the K-129 (2012). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2026 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Secret Offshore History of Drill Ship Glomar Explorer.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/secret-offshore-history-of-the-glomar-explorer. Last Updated: January 25, 2026. Original Published Date: February 8, 2020.