Million Dollar Auctioneer

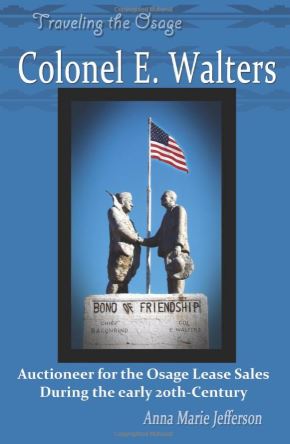

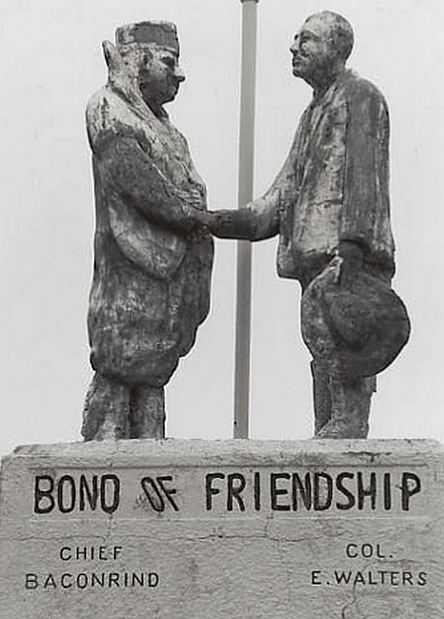

Friendship monument dedicated in 1926 preserves the history of Osage oil leases.

Colonel Elmer Ellsworth (his real name) Walters was the most famous auctioneer in all of Oklahoma history. In 1912, the Osage Indians hired him to auction mineral rights from their petroleum-rich reservation. By 1920, they had awarded him a gold medal for his skillful sales of Osage oil leases.

Walters was paid $10 a day while earning the tribe millions of dollars while working beneath a giant elm tree in Pawhuska. In April 1926, his Osage friends and residents dedicated a “Bond of Friendship” monument in Walters’ nearby hometown of Skedee.

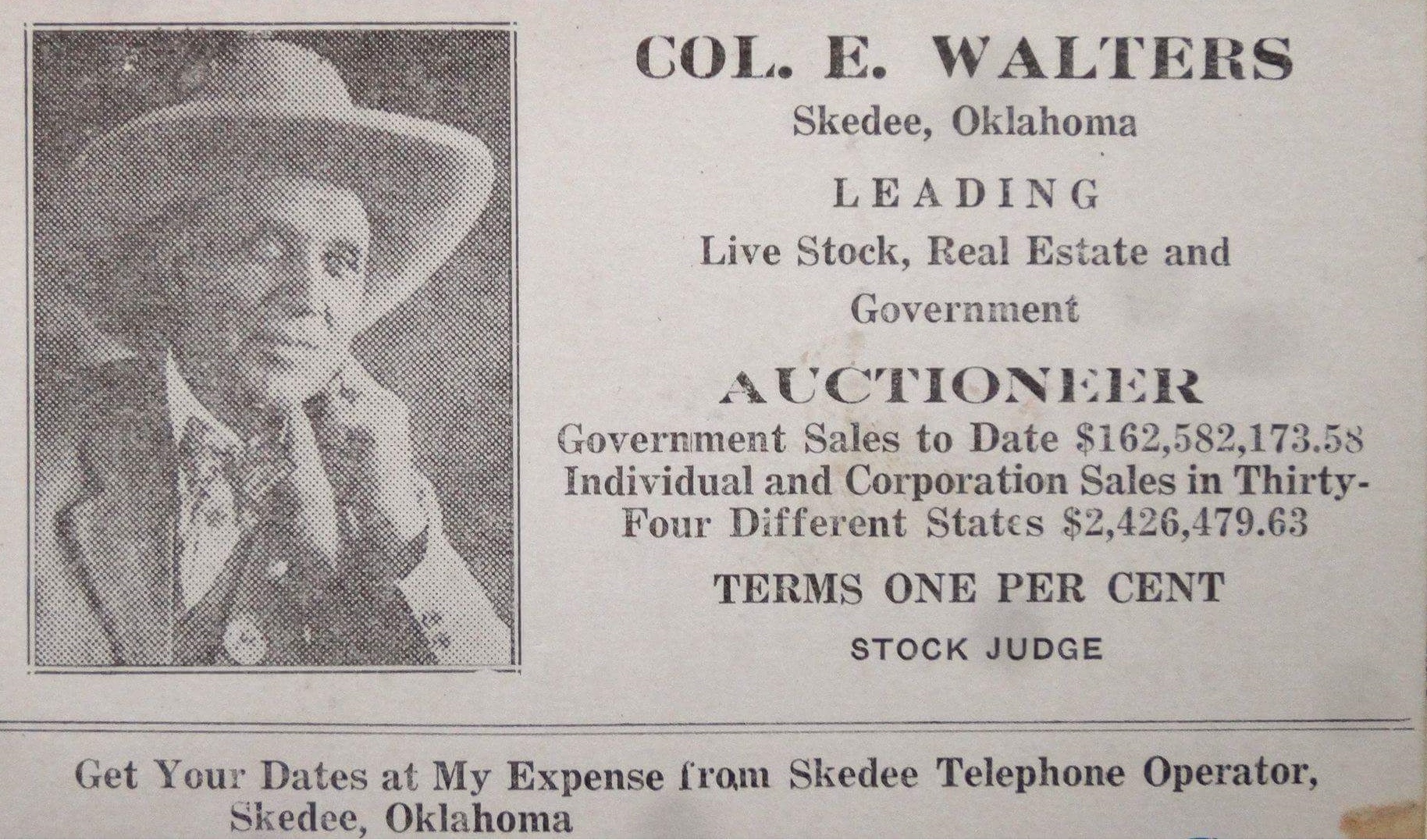

Newspaper ad courtesy of Colonel Walters’ great-great-granddaughter Hope Litvinoff. Her grandmother in 1926 helped unveil a statue in Skedee, Oklahoma, honoring Walters and the chief of the Osage Nation.

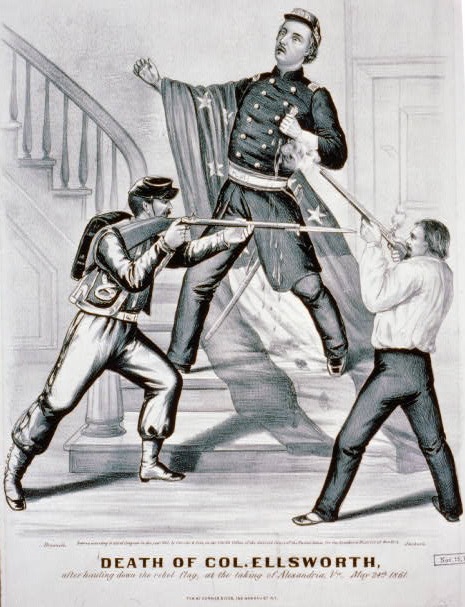

Born in Adrian, Illinois, in 1865, Walters was one year old when his parents moved to the Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory. He was named in honor of Col. Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth of the 11th New York Volunteers — the first Union officer killed at the start of the Civil War (shot while removing the Confederate flag from the roof of a hotel in Alexandria, Virginia).

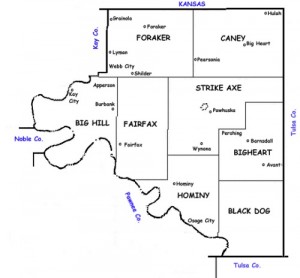

Although Walters became a deputy U.S. marshal at 19, he began gaining distinction as an auctioneer. He sold livestock, real estate and mineral leases in 2,250-square-mile Osage County.

Million Dollar Elm

Beginning in 1912, Walters sold Osage mineral leases in 160-acre blocks based on “headrights” from a 1906 tribal population count. In Pawhuska, between the Osage council house and the county courthouse, Walters called the auctions while standing in the shade of what became known as the “Million Dollar Elm.”

The bidders for the leases were a who’s who of leading Oklahoma independent producers. E.W. Marland biographer John J. Mathews quotes one impressed onlooker: “You could stand on the edge of the crowd and see two or three of the biggest names in America squatting there on the grass, as common as an old shoe, and when they raised their hands it meant millions. That’s a fact!”

Another onlooker described hundreds of spectators and reporters who gathered to watch the bidding. Walters proved so effective at “extracting millions from the silk pockets of such newly minted oil barons as Frank Phillips, E.W. Marland, and William G. Skelly” that the Osages awarded him a medal.

“On February 3, 1920, before that day’s bidding began, the Osage tribe presented Walters with a medal to show their appreciation for all the wealth he’d drummed up for them in the shade of the Million Dollar Elm,” the witness reported.

Born in 1865, Colonel E.E. Walters wasn’t actually a Colonel. He was named in honor of the first Union officer killed in the Civil War, complete with rank. Currier and Ives engraving, 1861. Image courtesy Library of Congress.

By 1922, the National Petroleum News proclaimed that Walters had “Sold 10 Times As Much Property Under Hammer As Any Other Man” and his friends, the Osage, became “the richest people in the world.”

Beneath the Pawhuska elm on March 18, 1924, Walters secured a bid of $1,995,000 for one 160-acre tract. It was the highest price paid at that time, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society. Walters reportedly received more Osage gifts, including a diamond-studded badge and a diamond ring for his auctions of Osage oil leases.

Dark Side of Headrights

Sudden great wealth for the Osage people brought a bloody criminal conspiracy of unsolved murders that left dozens of Osage men, women, and children dead — killed for the headrights to their land.

In the early 1920s, Colonel E.E. Walters stood in the shade of a soon-famous Elm tree to auction mineral leases, including a $2 million bid for a single 160-acre Osage lease. Detail from a photo in Oil! Titan of the Southwest by Carl Coke Rister, 1949.

“Osage mineral leases earned royalties that were paid to the tribe as a whole, with each allottee receiving one equal share, or headright, of the payments, noted Oklahoma Historical Society historian Jon D. May in Osage Murders.

“A headright was hereditary and passed to a deceased allottee’s immediate legal heir,” May added. “One did not have to be an Osage to inherit an Osage headright.”

Estimates vary, but at least 24 Osage Indians died violent or suspicious deaths during the early 1920s, when con men, bootleggers and murderers began a “Reign of Terror.”

William K. Hale was one of the worst. He was accused of repeatedly orchestrating murders, tried four times, and finally convicted of a single killing. The best-seller 2018 book Killers of the Flower Moon by journalist David Grann investigated the disturbing and tragic stories.

The New Yorker staff writer’s award-winning book would be adapted into a $200 million movie directed by Martin Scorsese, who acquired book rights in July 2017.

Sadly, at the time most Oklahoma news media ignored the reservation’s murders — and the murderers. Newspapers there and around the country instead featured scandalous stories of incredible Osage wealth squandered on Pierce-Arrows and gaudy fashion. As Osage Indians died, reporters mocked the tribe with sarcasm and caricatures.

In his 1994 book, Bloodland: A Family Story of Oil, Greed and Murder on the Osage Reservation, Washington Post journalist Dennis McAuliffe noted little wonder that, “this period in our history hardly dances with awareness.”

On April 22, 1926, hundreds gathered in Skedee, Oklahoma, for the unveiling of the 25-foot Bond of Friendship monument honoring the chief of the Osage Nation and the state’s greatest auctioneer of mineral rights.

As a result of the Osage murders, on February 27, 1925, the U.S. Congress passed the “Osage Indians Act of 1925,” a law prohibiting non-Osages from inheriting headrights of tribal members possessing more than one-half of Osage blood.

According to the Osage Nation, in 2022, “approximately 26 percent of all headrights are owned by non-Osage individuals, churches, universities, and other non-Osage institutions who can freely bequeath such interests to any person or entity the non-Osage chooses.

Bond of Friendship

On April 22, 1926, hundreds gathered in Walter’s longtime home of Skedee for the dedication of a 25-foot Bond of Friendship monument. The unveiling revealed “painted bronze” statues of Walters and the chief of the Osage Nation shaking hands on a two-tiered sandstone and concrete base.

Like the town, the Bond of Friendship of Skedee, Oklahoma, has deteriorated since 1926. Photo courtesy the Library of Congress.

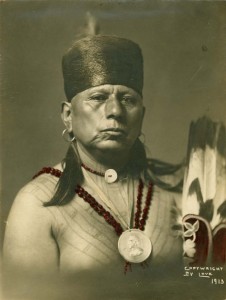

The friendship between Osage Chief (phonetically) Wah-she-hah and Walters left a statue in the Skedee town square. Wah-she-hah translates to Star-That-Travels in the Osage language — but history and visitors to the Skedee statue remember him as Chief Bacon Rind.

Still standing in Skedee, the 1926 sculpture depicts Osage Chief Bacon Rind wearing his traditional otter-skin cap and a cloak. Walters wears a suit with trousers tucked into his boots and holds a hat in his left hand. At the statue’s unveiling, the popular “auctioneer of the Osage Nation” had sold $157 million in lease sales for his friends. But it wasn’t all good news.

By the early 2020s, the Skedee Bond of Friendship monument began showing its age. The legacy of the once famous lease auctioneer and the Osage friendship provided some merriment for at least one contributor to Roadside America:

“The lesson imparted here is that white and red can be harmonious — if you just add a little green…Atop a blocky concrete pillar stands the Chief and the Colonel, facing each other, shaking hands. The work is primitive for such well-oiled honorees…while the Chief and the Colonel appear to be made of Play-Doh spray-painted silver.”

Although a traditionalist in customs, Chief Bacon Rind’s leadership earned his people millions from oil and natural gas resources.

However, the Osage Chief Bacon Rind, “a statuesque man at six feet four inches,” at one time was among the most photographed of all Native Americans. The Works Progress Administration noted the chief frequently posed for the prominent artists of the day “and created an image of the romantic ideal of the American Indian.”

Chief Bacon Rind died in 1932 and Walters followed in 1946. The population of Skedee peaked in 1910; a century later fewer than 50 residents remained. The tall but weathered monument remains in the center of town.

Walters, an amateur poet, had his hopes for the future carved into his hometown monument’s base:

…I will build for them a landmark,

That the coming race may see,

All the beauties of the friendship,

That exists ‘tween them and me…

And explain it to grandchildren,

as they sit upon their knee.

Preserving Osage Oil Stories

In 2018, an Osage writer decided to look deeper into Walter’s life and times. Already an author of several books about Osage history, Anna Marie Jefferson a year later published Colonel E. Walters: Auctioneer for the Osage Lease Sales During the early 20th-Century. Her research revealed many local newspaper accounts and rare images from his career.

Jefferson, who grew up in Osage County, remembered visiting the statue as a child in neighboring Pawnee County. “As an Osage (Sac and Fox/Pawnee as well) I was unaware of who Colonel E. Walters was, the man on top of the memorial.”

Familiar with Osage leader Bacon Rind, Jefferson began researching the life of Walters and his famed long career as a skilled auctioneer.

“When traveling the Osage, sometimes one needs to go just beyond the county lines to find early Osage Nation,” she explained in her book’s introduction. “Such is the case with the Bond of Friendship monument in the small town of Skedee, Oklahoma.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Underground Reservation: Osage Oil (1985); Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI

(2018); Colonel E. Walters: Auctioneer for the Osage Lease Sales During the early 20th-Century (2019). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Million Dollar Auctioneer.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/million-dollar-auctioneer. Last Updated: April 18, 2025. Original Published Date: March 27, 2015.