by Bruce Wells | Jan 10, 2021 | Petroleum Companies

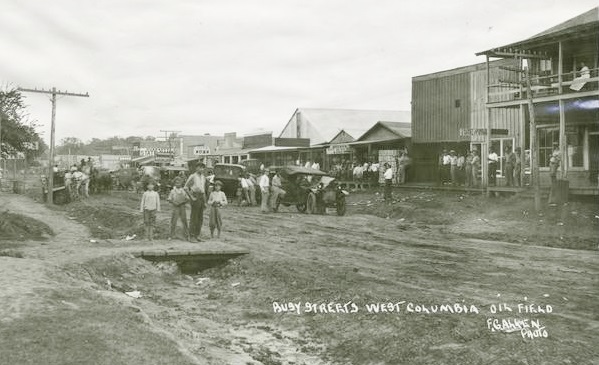

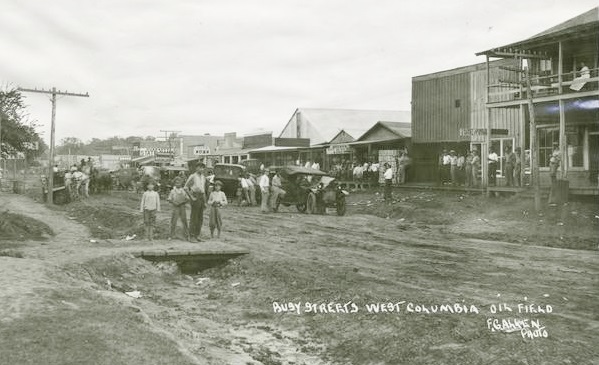

Lucky Jim Oil Company was created in March 1919 to pursue opportunities in the newly discovered West Columbia oilfield in Brazoria County, Texas (visit the Columbia Historical Museum in West Columbia to learn more about the first capital of the Republic of Texas).

The Brazoria County oilfield, 50 miles southwest of Houston, “was the youngest of the first rank salt dome oilfields of the Texas-Louisiana coastal region, and at present is the most productive of these fields,” reported the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG) in 1921.

Wind knocked down the first derrick of a Lucky Jim Oil Company well drilled in 1919. The well reached 3,340 feet before the company gave up – and reorganized as the Lucky Jim Junior Oil Company.

Like many competing exploration companies formed during Texas drilling booms, Lucky Jim Oil Company did not survive its first dry hole. A Lucky Jim Junior Oil Company fared no better.

West Columbia field

Wildcatters had become interested in the West Columbia after oil discoveries on a lease owned by a former Texas governor. Gov. J.S. “Big Jim” Hogg first thought oil might be there and leased the land in 1901 (learn more in Governor Hogg’s Texas Oil Wells).

When the Hogg No. 2 well was completed at 600 barrels of oil a day in January 1918, speculators rushed to lease nearby acreage. The 20-square-mile oilfield yielded more than 119,000 barrels of oil in 1918.

The Hogg discovery wells led to a local boom that attracted inexperienced, even fraudulent, drilling companies that would not long survive. They planned to drill near property with proven oil production.

Advertisements appeared in Texas newspapers that included $10 per share stock promotions enticing investment in the West Columbia oilfield — with a promise to pay out 75 percent of any net earnings to shareholders. The ads assured investors of early dividends and admonished, “Buy Today, Tomorrow May Be Too Late.”

The Texas Company (later Texaco) was among companies that found success in the 20-square-mile oilfield in Brazoria County. The field yielded more than 119,000 barrels of oil in 1918 alone.

Hedging against a dry hole and gambling on higher oil prices, Lucky Jim Oil declared in 1919, “We have immense holdings that we should be able to sell out on the present rise of prices in West Columbia, and pay our stockholders three or four for one on their investment without drilling a well.”

With funding from stock sales, the company was able to begin drilling its first well, the Brown No. 1, proclaiming it to be “within 1,800-feet of the Texas Company’s 20,000 barrel gusher.”

Drilling progressed for a few months until the derrick reportedly collapsed in high winds during a September storm. After rebuilding the wooden structure and resuming drilling, the well reached 3,340 feet. It was an expensive dry hole.

Lucky Jim Junior Oil Company

Within a month of the failed exploratory well, a reorganized Lucky Jim Junior Oil Company made its first appearance and tried again to secure funding to launch drilling operations in the crowded West Columbia oilfield.

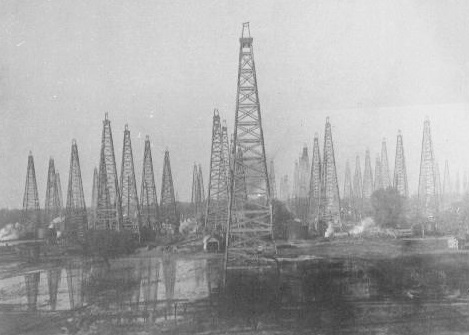

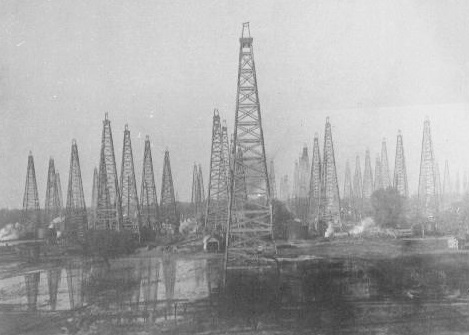

A drilling boom resulted in the West Columbia oilfield reaching its annual peak production of 12.5 million barrels of oil a few years after its discovery.

The new company did not succeed in raising enough capital and soon disappeared, along with many other such “poor boy” operations in South Texas at the time. Only larger companies could absorb costs of a dry hole and continue drilling.

The Texas Company (later Texaco) – after drilling several dry holes in the West Columbia field – in July 1920 brought in the Abrams No. 1 well, which produced 26,500 barrels a day for six weeks (see Sour Lake produces Texaco).

By 1921, the West Columbia field reached its peak annual production of 12.5 million barrels of oil — but by then the Lucky Jim Oil Company and Lucky Jim Junior Oil Company were both history.

The stories of many exploration companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Early Texas Oil: A Photographic History, 1866-1936 (2000); Wildcatters: Texas Independent Oilmen

(2000); Wildcatters: Texas Independent Oilmen (1984). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1984). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2021 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Lucky Jim Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/stocks/lucky-jim-oil-company. Last Updated: September 4, 2021. Original Published Date: September 8, 2015.

.

by Bruce Wells | Jun 15, 2015 | Petroleum Companies

Chances are people seeking financial information here at Old Oil Stocks – L will not find lost riches – see Not a Millionaire from Old Oil Stock. The American Oil & Gas Historical Society, which depends on donations, does not have resources to provide free research of corporate histories.

However, AOGHS continues to look into forum queries as part of its energy education mission. Some investigations have revealed little-known stories like Buffalo Bill’s Shoshone Oil Company; many others have found questionable dealings during booms and epidemics of “black gold” fever like Arctic Explorer turns Oil Promoter.

Visit the Stock Certificate Q & A Forum and view company updates regularly added to the A-to-Z listing at Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? AOGHS will continue to look into forum queries, including these “in progress.”

La Lomita Oil Syndicate

La Lomita Oil Syndicate began drilling near Mission, Texas, in 1920. The Hildalgo County well’s progress was tracked by a number of contemporary publications, including the Oil Trade Journal and Oil Weekly. By October 2, the Oblate Fathers No. 1 well reached 2,700 feet deep.

A week later, the San Antonio Express newspaper reported the syndicate’s well had added another 45 feet, but was confronted with stuck tools, requiring “fishing” of equipment stuck downhole.

The recovery effort stalled drilling for more than a month. Nonetheless, by February 1921 the well was reported to have a “showing of gas” and La Lomita Oil Syndicate was setting the well’s cement casing. Records are scant thereafter, but the September 30, 1922, issue of The Oil Weekly reported another problem well for La Lomita Oil Syndicate.

“La Lomita oil Syndicate’s Hill 3, trying to sdtr [sidetrack] 3,185 feet.” Sidetracking often resulted from stuck tools and failed fishing attempts. The process required plugging of the lower well-bore and drilling around the obstruction. The drill pipe allowed some flexibility for deviation from the vertical in an effort to save the well. Whether or not La Lomita oil Syndicate was successful in this effort remains mysterious, because the company disappears from records soon thereafter.

Lewiston-Clarkston Oil & Gas Company

Lewiston-Clarkston Oil and Gas Company was one of many companies that searched for oil unsuccessfully in the state of Washington. Lewiston, Idaho, is on the east side of the Snake River; Clarkston is across the river in Washington.

It was not until 1957 that Washington’s first and only commercial producer was discovered, The Sunshine Mining Company’s Medina No. 1, was coimpleted at 223 barrels of oil a day near Ocean City. It produced 12,500 barrels before being shut down in 1961.Lewiston-Clarkston Oil & Gas drilled two consecutive dry holes in Asotin County, Washington, near Swallow Rock and then appears to have run out of money. The wells (Section 5, Township 10 North, Range 46 East) reached depths of only 800 feet and 1,600 feet, according to driller’s logs.

Washington’s commissioner of public lands reported in 2010 about 600 wells had been drilled in the state, “but large-scale commercial production has never occurred. The most recent production, which was from the Ocean City Gas and Oil Field west of Hoquiam, ceased in 1962, and no oil or gas have been produced since that time.” Read about other historic wildcat wells in First Oil Discoveries.

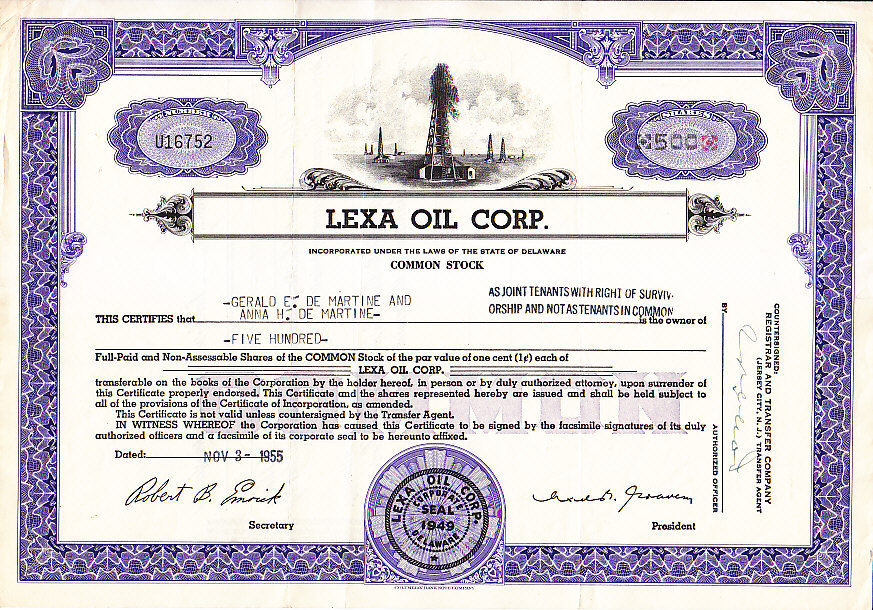

Lexa Oil Company

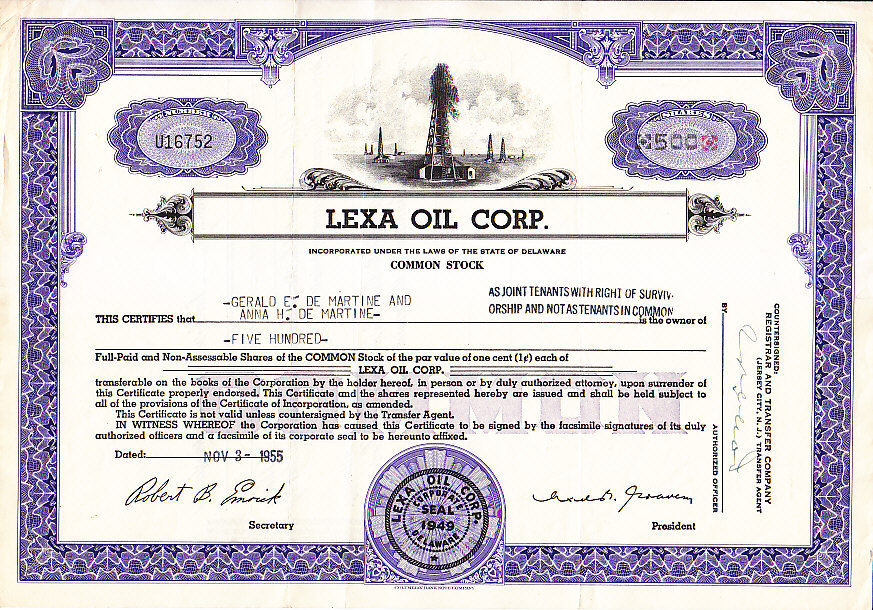

A fraudulent telephone campaign selling Lexa Oil Company stock resulted in two convictions. The pitchmen’s prevarications included:

A fraudulent telephone campaign selling Lexa Oil Company stock resulted in two convictions. The pitchmen’s prevarications included:

• The company had a well producing 250 barrels of oil a day;

• revenue from stock sales would be used for working capital;

• shares were being offered at a lower price than on the open market;

• Lexa Oil would be listed on a stock exchange;

• the investment was certain to produce high profits.

One offender received five years suspended and years’ probation. The other got two years probation. A total of 27,300 obsolete and valueless shares of Lexa Oil were destroyed by the Depository Trust Company in 2011.

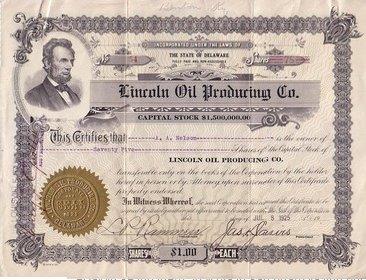

Lincoln Oil Producing Company

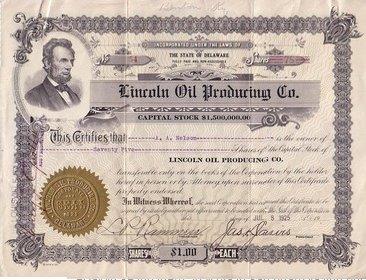

Kentuckians J.C. McCombs and H.A. Moore incorporated McCombs Oil Company in Delaware on September 7, 1917. It was soon renamed McCombs Producing & Refining Company and then Lincoln Oil Producing Company. Capitalization was five million shares at $1 par value.

Kentuckians J.C. McCombs and H.A. Moore incorporated McCombs Oil Company in Delaware on September 7, 1917. It was soon renamed McCombs Producing & Refining Company and then Lincoln Oil Producing Company. Capitalization was five million shares at $1 par value.

By 1919, dissatisfied minority shareholders brought successful suit against the “corporation and those in control of it” to cancel more than 680,000 shares of stock “for fraud.”

By 1921 – after extensive litigation – Lincoln Oil Producing Company was in receivership. The company attempted to recover in court and brought suit in 1925 but did not succeed despite multiple appeals. In 1929, a court ruling noted, “of those primarily liable, if liability existed, some were dead, some were gone from Kentucky, and some insolvent.”

Liquid Gold Oil Company

The Texas Railroad Commission may have information about Houston-based Liquid Gold Oil Company circa 1920. The commission has microfilm records that reach that booming era of Texas oil drilling. There have been other like-named companies that left behind better records (e.g., Montana Liquid Gold Oil Company incorporated in 1930 and drilled at least one well in Toole County). Another “liquid gold” corporation was active in the 1970s, but was bankrupt by 1982.

Louisiana Consolidated Petroleum Company

Louisiana Consolidated Petroleum Company in 1920 declared its stock would pay a 100 percent dividend. For $1 a share, the company’s stock could be purchased by mailing in a coupon with payment. To see this advertisement, do an internet search with quotes for “Louisiana Consolidated Petroleum” and your search should bring you to the December 3, 1920, issue of the Mexia (Texas) Weekly Herald. The enthusiastic Louisiana Consolidated Petroleum advertisement is typical of the times.

Like many under-capitalized and speculative ventures, Louisiana Consolidated Petroleum exaggerated its financial potential. Extravagant and unsubstantiated stock promotions were as common as patent medicine advertisements. “Blue Sky” laws requiring more accurate disclosures later became part of the investment landscape. State laws targeted those “engaging in any practice or transaction or course of business relating to the purchase, exchange, investment advice, or sale of securities or commodities which is fraudulent, or in violation of law, or would operate as a fraud on the purchaser.”

Love Petroleum Company

Love Petroleum Company was founded by James Wesley Love and registered in Mississippi on July 1, 1930. It drilled successful oil and natural gas wells along with dry holes. Love, who died in 1957, was noted for developing Louisiana’s Tullos-Urania oilfield.

The Mississippi Oil and Gas Board maintains records that can be seen online. By the 1990s Love Petroleum had been acquired by Southwest Royalties Inc. and had exited Mississippi to conduct business out of Midland, Texas. Southwest Royalties was acquired by Clayton Williams Energy Inc.

Loy Oil Company

Loy Oil Company was formed by the former mayor of Chanute, Kansas, and long-time independent drilling contractor Henry Wilbert “Bert” Loy in 1935, when he was 64 years old. Loy had helped pioneer the petroleum business in eastern Kansas after moving to Chanute in 1903 from Aurora, Missouri.

Loy drilled successful wells as early as 1909; these can be located in the Kansas Geological Survey oil and gas well database. The records do not indicate that Loy Oil Company survived; Henry Wilbert Loy died in 1953 at 81. The Chanute Historical Society maintains a website and contact information which may further assist in research. Learn Kansas oil history in Kansas Oil Boom.

Lucky Long Oil Company

The Lucky Long Oil Company organized on January 4, 1918, with capitalization of $50,000 divided into five million shares of stock at one cent par value.

Promoters received 1,250,000 shares with the balance held in the treasury while stock sales commissions of 25 percent were paid mostly to the company’s officers. As reported in Denver’s June 1918 Municipal Facts publication, Lucky Long Oil was specifically named in a “blue sky” investigation whose objective was to “Warn Investors Against Fake Stocks.”

The investigation revealed Lucky Long Oil had lured potential investors with spurious “guaranteed 24 percent dividends per year” and sold stock before acquiring any leases. Lucky Long Oil was assessed to have “not even a long chance speculative value” and blasted for using “clearly untruthful and misleading” advertising. President A.J. Long absconded to Wyoming and Lucky Long Oil Company disappeared.

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this AOGHS.ORG energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2020 Bruce A. Wells.

(2000); Wildcatters: Texas Independent Oilmen

(1984). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

A fraudulent telephone campaign selling Lexa Oil Company stock resulted in two convictions. The pitchmen’s prevarications included:

A fraudulent telephone campaign selling Lexa Oil Company stock resulted in two convictions. The pitchmen’s prevarications included: Kentuckians J.C. McCombs and H.A. Moore incorporated McCombs Oil Company in Delaware on September 7, 1917. It was soon renamed McCombs Producing & Refining Company and then Lincoln Oil Producing Company. Capitalization was five million shares at $1 par value.

Kentuckians J.C. McCombs and H.A. Moore incorporated McCombs Oil Company in Delaware on September 7, 1917. It was soon renamed McCombs Producing & Refining Company and then Lincoln Oil Producing Company. Capitalization was five million shares at $1 par value.