This Week in Petroleum History, February 10 – 16

February 10, 1910 – Giant Oilfield discovered in California –

Honolulu Oil Corporation discovered the Buena Vista oilfield in Kern County, California. The well, originally known as “Honolulu’s Great Gasser,” drilled deep into oil-producing sands for production of 3,500 barrels of oil a day. Steam injection operations helped the field produce “heavy” (high viscosity) oil from depths near 4,000 feet.

In 1912, as the Navy began converting its warship boilers from coal to oil (see Petroleum & Sea Power), the San Joaquin Valley oilfield was designated Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 2. The Department of Energy leased 90 percent of the 30,000-acre Buena Vista reserves to private oil companies in 2020.

February 10, 1917 – Petroleum Geologists get Organized in Tulsa

About 90 geologists gathered in Oklahoma to form an association where “only reputable and recognized petroleum geologists are admitted.” They met at Henry Kendall College, now Tulsa University, to establish the Southwestern Association of Petroleum Geologists, today’s American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG).

Adopting its current name in 1918, AAPG also launched its peer-reviewed scientific journal, the Bulletin. By 1920, industry trade magazines were praising the association’s professionalism and success in combating, “unscrupulous and inadequately prepared men who are attempting to do geological work.”

AAPG in 1945 formed a committee to assist the Boy Scouts of America with a geology merit badge and the AAPG Foundation supports a Distinguished Lecture program. The association’s 2025 membership has reached almost 40,000 members, including 8,000 students, in 129 countries.

Learn more in AAPG – Geology Pros since 1917.

February 10, 1956 – Frank Lloyd Wright’s “Prairie Skyscraper”

Harold C. Price Sr., founder of the pipeline construction company H.C. Price, dedicated his headquarters building in Bartlesville, Oklahoma. The 19-story concrete and copper office tower remains the only skyscraper designed by architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

Established in 1921, H.C. Price specialized in field welding oil storage tanks and electric welding of pipelines. The company helped construct the “Big Inch” pipelines during WWII and built large sections of the 800-mile Trans-Alaska Pipeline.

Once a pipeline company headquarters, the Price Tower in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974. Photo by Bruce Wells.

Wright — who in 1954 designed the Price family residence in Phoenix, Arizona — created the Bartlesville “Prairie Skyscraper” in four quadrants, “based on the geometry of a 30-60-90 degree double parallelogram module” with one quadrant for apartments and three for offices, according to the current occupant, Price Tower Arts Center. The National Register of Historic Places added the former pipeline company headquarters building in 1974.

February 12, 1954 – First Nevada Oil Well

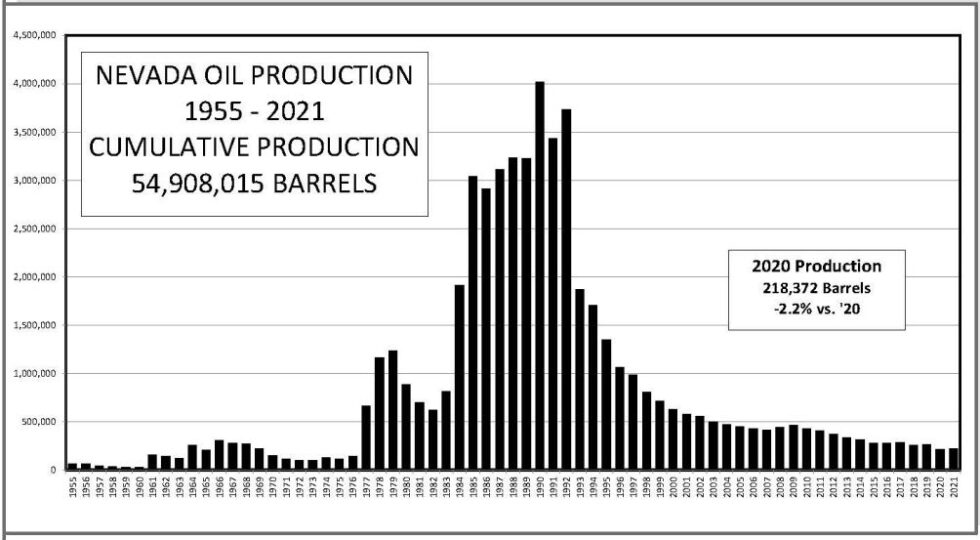

After hundreds of dry holes (the first drilled near Reno in 1907), Nevada became a petroleum-producing state. Shell Oil Company’s second test of its Eagle Springs No. 1 well in Nye County produced commercial amounts of oil. The routine test revealed petroleum production from depths between 6,450 feet and 6,730 feet.

Nevada’s annual oil production peaked in 1990 at about 4 million barrels of oil. Chart courtesy Nevada Division of Minerals.

Although the Eagle Springs field eventually produced 3.8 million barrels of oil, finding Nevada’s second oilfield took two more decades. Northwest Exploration Company completed the Trap Spring No. 1 well in Railroad Valley, five miles west of the Eagle Springs oilfield in 1976.

Learn more in First Nevada Oil Well.

February 12, 1987 – Texaco Fine upheld for Getty Oil Takeover attempt

A Texas court upheld a 1985 decision against Texaco for having initiated an illegal takeover of Getty Oil after Pennzoil had made a bid for the company. By the end of the year, the companies settled their historic $10.3 billion legal battle for $3 billion when Pennzoil agreed to drop its demand for interest.

The compromise was vital for a reorganization plan for Texaco emerging from bankruptcy, a haven it had sought to stop Pennzoil from enforcing the largest court judgment ever awarded at the time, according to the Los Angeles Times.

February 13, 1924 – Forest Oil adopts Yellow Dog Logo

Forest Oil Company, founded in 1916 as an oilfield service company by Forest Dorn and his father Clayton, adopted a logo featuring the two-wicked “yellow dog” oilfield lantern. The logo included a keystone shape to symbolize the state of Pennsylvania, where Forest Oil pioneered water-flooding methods to improve production from the 85,000-acre Bradford oilfield.

Forest Oil Company adopted the “yellow dog” lantern logo in 1924. eight years after being founded in Bradford, Pennsylvania,

Forest Oil Company‘s oilfield water-injection technology, later adopted throughout the petroleum industry, helped keep America’s first billion-dollar oilfield producing to the present day. Patented in 1870, the popular derrick lamp’s name was said to come from the two burning wicks resembling a dog’s eyes glowing at night.

Learn more in Yellow Dog – Oilfield Lantern.

February 13, 1977 – Texas Ranger “El Lobo Solo” dies

“El Lobo Solo” — The Lone Wolf — Texas Ranger Manuel T. Gonzaullas died at age 85 in Dallas. During much of the 1920s and 1930s, he had earned a reputation as a strict law enforcer in booming oil towns.

When Kilgore became “the most lawless town in Texas” after discovery of the East Texas oilfield in 1930, Gonzaullas was chosen to tame it. “Crime may expect no quarter in Kilgore,” the Texas Ranger once declared. He rode a black stallion named Tony and sported a pair of 1911 .45 Colts with his initials on the handles.

“He was a soft-spoken man and his trigger finger was slightly bent,” noted independent producer Watson W. Wise in 1985. “He always told me it was geared to that .45 of his.”

Learn more in Manuel “Lone Wolf” Gonzaullas, Texas Ranger

February 15, 1982 – Deadly Atlantic Storm sinks Drilling Platform

With rogue waves reaching as high as 65 feet during an Atlantic cyclone, offshore drilling platform Ocean Ranger sank on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, Canada, killing all 84 on board. At the time the world’s largest semi-submersible platform, the Ocean Ranger had been drilling a third well in the Hibernia oilfield for Mobil Oil of Canada.

The deadly weather system also engulfed a Soviet container ship 65 miles east of the platform, resulting in the loss of 32 crew members. A 1983 Coast Guard Marine Casualty Report about Ocean Ranger led to improved emergency procedures, lifesaving equipment, and manning standards for Mobile Offshore Drilling Unit (MODU) operations.

February 16, 1935 – Petroleum Producing States form Commission

A multi-state government agency that would become the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission was organized in Dallas with adoption of the “Interstate Compact to Preserve Oil and Gas.” Approved by Congress in August, the commission established its headquarters in Oklahoma City.

Headquarters of the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission (IOGCC) on property adjacent to the governor’s mansion in Oklahoma City since the 1930s.

Representatives from Colorado, Illinois, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas began planning initiatives, “to conserve oil and gas by the prevention of physical waste thereof from any cause.” Oklahoma Gov. Ernest W. Marland — founder of Marland Oil Company in 1921 — was elected the first chairman.

“Faced with unregulated petroleum overproduction and the resulting waste, the states endorsed and Congress ratified a compact to take control of the issues,” according to IOGCC, which added the word gas to its name in 1991.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Black Gold in California: The Story of California Petroleum Industry (2016); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975); Building Bartlesville, 1945-2000, Images of America: Oklahoma

(2008); Roadside Geology of Nevada

(2017); The Taking of Getty Oil: Pennzoil, Texaco, and the Takeover Battle That Made History

(2017); Images of America: Around Bradford

(1997); Lone Wolf Gonzaullas, Texas Ranger (1998); The Ocean Ranger: Remaking the Promise of Oil (2012); Oil in Oklahoma

(1976). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support energy education, help maintain the AOGHS website, and expand historical research for scribers to the monthly “Oil & Gas History News.” For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.