This Week in Petroleum History: March 24 – 30

March 24, 1989 – Exxon Valdez hits Bligh Reef –

After almost 12 years of routine passages by oil tankers through Prince William Sound, Alaska, supertanker Exxon Valdez ran aground on Bligh Reef, resulting in an oil spill affecting 1,300 miles of shoreline. Vessels carrying North Slope oil had safely passed through the sound more than 8,700 times.

Eight of Exxon Valdez’s 11 tanks were punctured and an estimated 260,000 barrels of oil spilled, affecting hundreds of miles of coastline. Investigators later found that an error in navigation by the third mate, possibly due to fatigue or excessive workload, had caused the accident.

Shown being towed away from Bligh Reef, the Exxon Valdez had been outside shipping lanes when it ran aground in March 1989. Photo courtesy Erik Hill, Anchorage Daily News.

When the 987-foot tanker hit the reef that night, “the system designed to carry two million barrels of North Slope oil to West Coast and Gulf Coast markets daily had worked perhaps too well,” noted the Alaska Oil Spill Commission. “At least partly because of the success of the Valdez tanker trade, a general complacency had come to permeate the operation and oversight of the entire system.”

Learn more in Exxon Valdez Oil Spill.

March 26, 1930 – “Wild Mary Sudik” makes Headlines

What would become one of Oklahoma’s most famous wells struck a high-pressure formation about 6,500 feet beneath Oklahoma City and oil erupted skyward. The Indian Territory Illuminating Oil Company’s Mary Sudik No. 1 flowed for 11 days before being brought under control. It produced about 20,000 barrels of oil and 200 million cubic feet of natural gas daily, becoming a worldwide sensation.

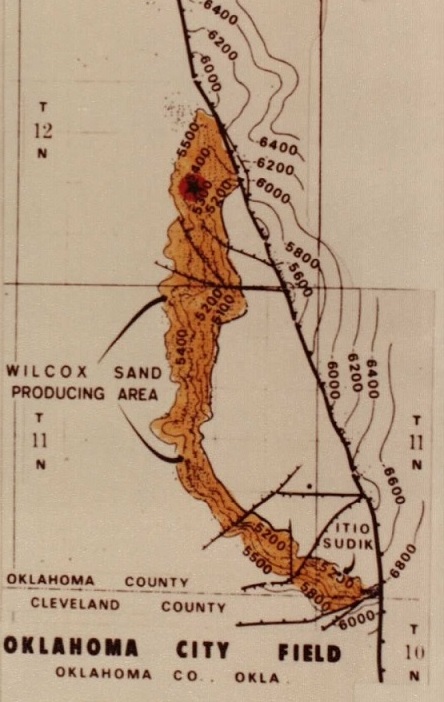

Highly pressured natural gas from the Wilcox formation proved difficult to control in the prolific Oklahoma City oilfield. Within a week of a 1930 gusher, Hollywood newsreels of it appeared in theaters across America. Photo courtesy Oklahoma History Center.

Efforts to control the well in Oklahoma City’s prolific oilfield (discovered in 1928) were featured on movie newsreels and national radio broadcasts. It was later learned that after drilling more than a mile deep, the exhausted crew did not realize the Wilcox Sand oil formation was permeated with highly pressurized natural gas.

Although the first ram-type blowout preventer (BOP) had been patented in 1926, deep oil and natural gas fields would take time to tame.

Learn more in “Wild Mary Sudik.”

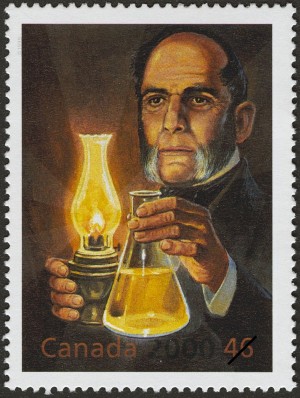

March 27, 1855 – Canadian Chemist trademarks Kerosene

Canadian physician and chemist Abraham Gesner (1797-1864) patented a process to distill coal into kerosene. “I have invented and discovered a new and useful manufacture or composition of matter, being a new liquid hydrocarbon, which I denominate Kerosene,” he proclaimed. Because his new illuminating fluid was extracted from coal, consumers called it “coal oil” as often as kerosene.

On March 17, 2000, Canada issued one million commemorative stamps featuring kerosene inventor Abraham Gesner.

Gesner, considered the father of the Canadian petroleum industry, in 1842 established Canada’s first natural history museum, the New Brunswick Museum, which today houses one of Canada’s oldest geological collections. America’s petroleum industry began when it was learned oil could be distilled into a lamp fuel.

Learn more in Camphene to Kerosene Lamps.

March 27, 1975 – First Pipe laid for Trans-Alaskan Pipeline

With the laying of the first section of pipe in Alaska, construction began on the largest private construction project in American history at the time. Recognized as a landmark of engineering, the 800-mile Trans-Alaska Pipeline system, including pumping stations and the Valdez Marine Terminal, would cost $8 billion by the time it was completed in 1977.

Learn more in Trans-Alaska Pipeline History.

March 27, 1999 – Offshore Platform Rocket Launch Test

The Ocean Odyssey, a converted semi-submersible drilling platform, launched a Russian rocket that placed a demonstration satellite into geostationary orbit.

The Zenit-3SL rocket, fueled by liquid oxygen and kerosene rocket fuel, was part of Sea Launch, a Boeing-led consortium of companies from the United States, Russia, Ukraine, and Norway. The platform had once been used by Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO) for North Sea exploration.

With an orbital test on March 27, 1999, the Ocean Odyssey, a converted semi-submersible drilling platform, became the world’s first floating equatorial launch pad. Photo courtesy Sea Launch.

“The Sea Launch rocket successfully completed its maiden flight today,” Boeing announced. “The event, which placed a demonstration payload into geostationary transfer orbit, marked the first commercial launch from a floating platform at sea.”

The Sea Launch consortium provided orbital launch services until 2014, when Russia annexed the Crimean Peninsula of Ukraine.

Learn more in Offshore Rocket Launcher.

March 28, 1886 – Natural Gas Boom begins in Indiana

Petroleum exploration companies converged on Portland, Indiana, after the Eureka Gas and Oil Company discovered a natural gas field after drilling just 700 feet deep. The well began producing two months after a spectacular natural gas well about 100 miles to the northeast — the “Great Karg Well” of Findlay, Ohio.

According to industrialist Andrew Carnegie, natural gas daily replaced 10,000 tons of coal for making steel.

Portland foundry owner Henry Sees had followed the news from Findlay. He persuaded local investors to drill for Indiana natural gas. In western Pennsylvania, reserves found near Pittsburg had encouraged industrialists there to replace their coal-fired steel and glass foundries with the first large-scale industrial use of natural gas.

Indiana would become the world’s largest natural gas producer, thanks to its Trenton limestone stretching more than 5,100 square miles across 17 counties. Within three years, more than 200 companies were drilling, distributing, and selling natural gas.

Learn more in Indiana Natural Gas Boom.

March 28, 1905 – Oil Discovered in North Louisiana

A small oil discovery in Caddo Parish launched a drilling boom in northern Louisiana and brought economic prosperity to Oil City. The Offenhauser No. 1 well was completed at a depth of 1,556 feet, but yielded just five barrels of oil a day and was abandoned. Far more productive wells quickly followed as the Caddo-Pine Island oilfield 20 miles northwest of Shreveport expanded into 80,000 acres.

The Shreveport Chamber of Commerce in 1955 dedicated a 40-foot monument commemorating the 50th anniversary of oil in Caddo Parish. Photo by Bruce Wells.

“This part of Louisiana, of course, was built on the oil and gas industry, and those visitors interested in the technical aspects of oilfield work will find the museum particularly appealing,” notes the Louisiana State Oil and Gas Museum (formerly the Caddo-Pine Island Oil and Historical Museum). More oilfield history can be found in Shreveport, where natural gas was discovered in 1870 — thanks to an ice plant’s water well. To discourage natural gas flaring, Louisiana passed its first conservation law in 1906.

Learn more in Louisiana Oil City Museum.

March 29, 1819 – Birthday of Father of the Petroleum Industry

Edwin Laurentine Drake (1819-1880) was born in Greenville, New York. Forty years later, he used a steam-powered cable-tool rig to drill the first commercial U.S. oil well at Titusville, Pennsylvania. The former railroad conductor overcame many financial and technical obstacles to make “Drake’s Folly” a milestone in U.S. petroleum history.

Edwin L. Drake (1819-1880) invented a method of driving a pipe down to protect the integrity of the first U.S. oil well. Photo courtesy Drake Well Museum.

Drake pioneered using iron casing to isolate his well from nearby Oil Creek. “In order to overcome the hurdles before him, he invented a ‘drive pipe’ or ‘conductor,’ an invention he unfortunately did not patent,” noted historian Urja Davé in 2008. “Mr. Drake conceived the idea of driving a pipe down to the rock through which to start the drill.”

Determined to find oil for refining into kerosene, Drake drilled near natural seeps and found oil on August 27, 1859, at a depth of 69.5 feet at a site today on the grounds of the Drake Well Museum.

Learn more in Edwin Drake and his Oil Well.

March 29, 1938 – Magnolia Oilfield found in Arkansas

“Kerlyn Wildcat Strike In Southern Arkansas is Sensation of the Oil Country,” proclaimed the local newspaper when a well drilled by Kerlyn Oil Company revealed the 100-million-barrel Magnolia oilfield, adding to the 1920s giant oilfield discoveries at El Dorado and Smackover.

Drilling on the Barnett No. 1 well had been suspended because of a lack of money, but geologist and company Vice President Dean McGee urged drilling deeper. He was rewarded with a giant oilfield discovery at the depth of 7,650 feet. McGee later would become an industry pioneer in offshore exploration.

Visit the Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources in Smackover.

March 30, 1980 – Deadly North Sea Gale

Massive waves during a North Sea gale capsized a floating apartment for Phillips Petroleum Company workers, killing 123 people. The Alexander Kielland platform, 235 miles east of Dundee, Scotland, housed 208 men who worked on a nearby rig in the Ekofisk field. Most of the Phillips workers were from Norway. The platform, converted from a semi-submersible drilling rig, served as overflow accommodation for the Phillips production platform 300 yards away.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Exxon Valdez Oil Spill, Perspectives on Modern World History (2011); The Oklahoma Petroleum Industry

(1980); Oil Lamps The Kerosene Era In North America

(1978); Amazing Pipeline Stories: How Building the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Transformed Life in America’s Last Frontier

(1997); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2009); Texas Oil and Gas, Postcard History

(2013); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946

(1982). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.