This Week in Petroleum History: July 14 – 20

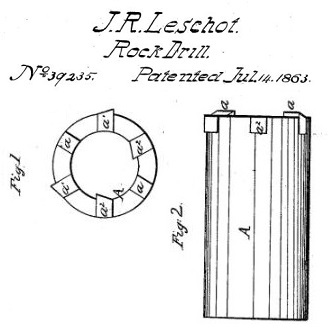

July 14, 1863 – Patent issued for “Tool for Boring Rock” –

French tunnel engineer Rodolphe Leschot received a U.S. patent for a “Tool for Boring Rock.” His concept included a ring of industrial-grade diamonds on the end of a tubular drill rod designed to cut a cylindrical core. Water pumped through the drill rod, washed away cuttings and cooled the bit. Leschot’s system proved successful in drilling blast holes for tunneling.

At the same time, the use of diamond bits in oil well drilling was being examined in the petroleum regions of western Pennsylvania. It is not known if there is any connection between the 1865 experimental diamond core drilling in Pennsylvania and the Leschot blast hole drilling in France.

July 14, 1891 – Rockefeller expands Tank Car Empire

John D. Rockefeller incorporated the Union Tank Line Company in New Jersey and transferred his fleet of several thousand oil tank cars to the Standard Oil Trust. He then systematically acquired control of all but 200 of America’s 3,200 tank cars. By 1904, the rolling fleet had grown to 10,000.

Union Tank Line Company shipped only Standard Oil products until 1911, when the U.S. Supreme Court mandated the dissolution of Standard Oil. The new shipping company changed its name to Union Tank Car Company (keeping Standard Oil’s UTL or UTLX markings seen today). The company introduced a 50,000-gallon tank car in 1963, the largest in rail service at the time.

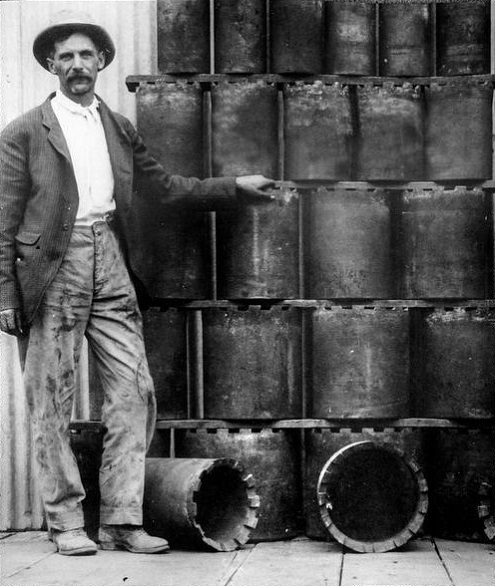

July 16, 1907 – Drilling Pioneer patents Casing Shoe

After drilling wells in Kern River oilfields, R. Carlton “Carl” Baker (1872-1957) of Coalinga, California, patented the Baker well-casing shoe. His cable-tool innovation at the bottom of the casing string increased efficiency and reliability for ensuring oil flowed through a well.

Reuben Carlton “Carl” Baker standing next to Baker Casing Shoes in 1914. Photo courtesy R.C. Baker Memorial Museum.

Baker, who in 1903 founded the Coalinga Oil Company, by 1913 had established the Baker Casing Shoe Company (renamed Baker Tools two years later). The inventor opened his first manufacturing plant in Coalinga before moving headquarters to Los Angeles in the 1930s. The company became Baker International in 1976 and Baker Hughes after a 1987 merger with Hughes Tool Company.

Learn more in Carl Baker and Howard Hughes.

July 16, 1926 – Oil Discovery launches Seminole Drilling Boom

Three years after an oil well was completed near Bowlegs, Oklahoma, a gusher south of Seminole revealed the true oil potential of Seminole County. The Fixico No. 1 well penetrated the prolific Wilcox Sands formation at a depth of 4,073 feet.

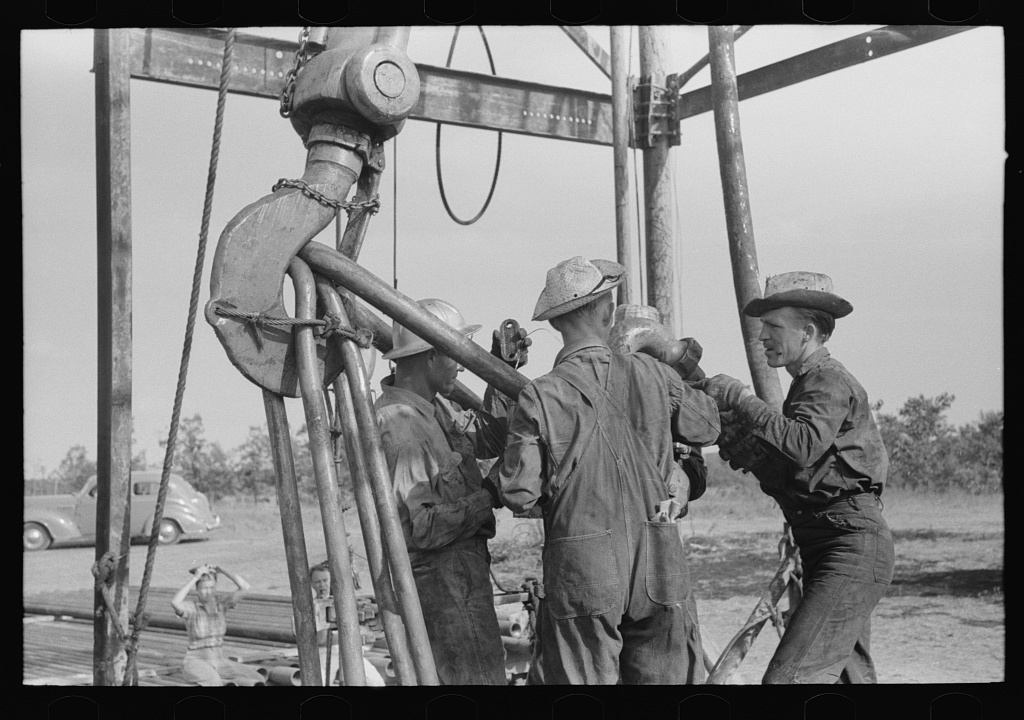

“Oil workers working on lowered traveling block” at well in Seminole oilfield, August 1939. Photo by Russell Lee (1903-1986) courtesy Library of Congress.

Drilled by R.F. Garland and his Independent Oil Company, the well was among more than 50 Greater Seminole Area oil reservoirs discovered; six were giants that produced more than one million barrels of oil each. With the Oklahoma City oilfield added in 1928, Oklahoma became the largest supplier of oil in the world by 1935.

Learn more in Seminole Oil Boom.

July 16, 1935 – Oklahoma Oil Boom brings First Parking Meter

As the booming Oklahoma City oilfield added to the congestion of cars downtown, the world’s first parking meter was installed at the corner of First Street and Robinson Avenue. Carl C. Magee, publisher of the Oklahoma News, designed the Park-O-Meter No. 1, today preserved by the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Oklahoma college students helped Carl Magee design the Park-O-Meter No. 1. Photo courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society.

“The meter charged five cents for one hour of parking, and naturally citizens hated it, viewing it as a tax for owning a car,” noted historian Josh Miller in 2012. “But retailers loved the meter, as it encouraged a quick turnover of customers.”

Park-O-Meters were manufactured by the MacNick Company of Tulsa, maker of timing devices used to detonate nitroglycerin in wells — and an oilfield services competitor of Zebco, the Zero Hour Bomb Company.

July 16, 1969 – Kerosene fuels launch of Saturn V Moon Rocket

A 19th-century petroleum product made America’s 1969 moon landing possible. Kerosene powered the first-stage rocket engines of the Saturn V when it launched the Apollo 11 mission on July 16. Four days later, astronaut Neil Armstrong announced, “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

Powered by five first-stage engines fueled by “rocket grade” kerosene, the Saturn V was the tallest, heaviest and most powerful rocket ever built until the SpaceX Starship. Photos courtesy NASA.

Five engines of the Saturn V’s first stage burned “Rocket Grade Kerosene Propellant” at 2,230 gallons per second, generating almost eight million pounds of thrust. The fuel was a highly refined kerosene RP-1 (Rocket Propellant-1) that began as “coal oil” for lamps.

When Canadian Abraham Gesner (1797-1864) first refined the lamp fuel from coal in 1846, he coined the term kerosene from the Greek word keros (wax), but many people called it “coal oil.” A highly refined version of his product now fuels rockets, including the SpaceX Falcon 9.

Learn more in Kerosene Rocket Fuel.

July 18, 1929 – Darst Creek Oilfield discovered in West Texas

With initial production of 1,000 barrels of oil a day, the Texas Company No. 1 Dallas Wilson well revealed a new West Texas oilfield at Darst Creek in Guadalupe County, about five miles from the southwestern edge of the Luling oilfield. The field would be developed by Humble Oil and Refining (later Exxon), Gulf Production Company, Magnolia Petroleum (later Mobil), as well as the Texas Company (later Texaco).

The Petroleum Museum of Midland, Texas, erected in 2019 a circa 1930 derrick used in the Darst Creek oilfield. Photo courtesy the Petroleum Museum.

By December 1931, the Darst Creek field produced more than 19.7 million barrels of oil from an average depth of 2,650 feet, according to a Humble Oil geologist, who noted that of the 291 wells drilled, just 19 were dry holes. The West Texas field was also among the first to operate under proration.

“To avoid the risks of unregulated production with a resulting loss of reservoir pressure, water encroachment and cheap crude prices, the operators agreed to voluntary proration in the field,” noted the Petroleum Museum, adding that “voluntary proration proved to be difficult to maintain.” The Midland museum celebrates its 50th year of preserving Permian Basin history this September.

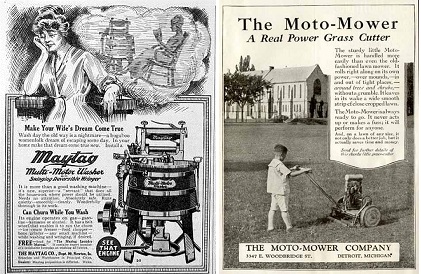

July 19, 1915 – Petroleum powers Washers and Mowers

Howard Snyder applied to patent his internal combustion-powered washing machine, assigning the rights to the Maytag Company. His washer for “the ordinary farmer” who lacked access to electricity used a one-cylinder, two-cycle engine that could operate using gasoline, kerosene, or alcohol.

Advertisements featured two popular consumer products powered by air-cooled internal combustion engines.

Four years later, Edwin George of Detroit removed the engine from his wife’s Maytag washing machine and added it to a reel-type lawnmower. His invention launched the Moto-Mower Company, which sold America’s first commercially successful gasoline-powered lawn mower.

July 19, 1957 – Oilfield discovered in Alaska Territory

Although some oil production had occurred earlier in the territory, Alaska’s first commercial oilfield was discovered by Richfield Oil Company, which completed its Swanson River Unit No. 1 in Cook Inlet Basin. The well yielded 900 barrels of oil per day from a depth of 11,215 feet.

Even the Anchorage Daily Times could not predict oil production would account for more than 90 percent of Alaska’s revenue.

Alaska’s first governor, William Egan, proclaimed the oilfield discovery provided “the economic justification for statehood for Alaska” in 1959. Richfield leased more than 71,000 acres of the Kenai National Moose Range, now part of the 1.92 million-acre Kenai National Wildlife Refuge.

By June 1962, about 50 wells were producing more than 20,000 barrels of oil a day. Richfield Oil Company merged with Atlantic Refining Company in 1966, becoming Atlantic Richfield (ARCO), which with Exxon discovered the giant Prudhoe Bay field in 1968.

Learn more in First Alaska Oil Wells.

July 20, 1920 – Discovery Well of the Permian Basin

The Permian Basin made headlines in 1920 when a wildcat well erupted oil from a depth of 2,750 feet on land owned by Texas Pacific Land Trust agent William H. Abrams, who just weeks earlier had discovered the West Columbia oilfield in Brazoria County south of Houston.

The latest W.H. Abrams No. 1 well — “shot” with nitroglycerin by the Texas Company (later Texaco) — proved to be part of the Permian Basin, encompassing 75,000 square miles in West Texas and southeastern New Mexico.

According to a Mitchell County historical marker, “land that sold for 10 cents an acre in 1840 and $5 an acre in 1888 now brought $96,000 an acre for mineral rights, irrespective of surface values…the flow of oil money led to better schools, roads and general social conditions.”

In 1923, the Santa Rita No. 1 discovery well near Big Lake brought yet another Texas drilling boom — and helped establish the University of Texas.

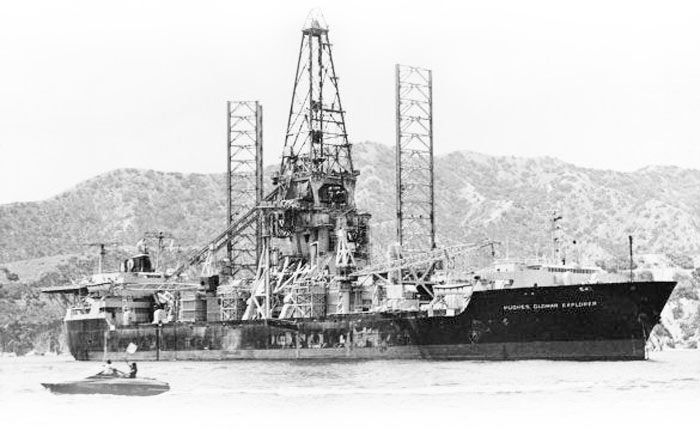

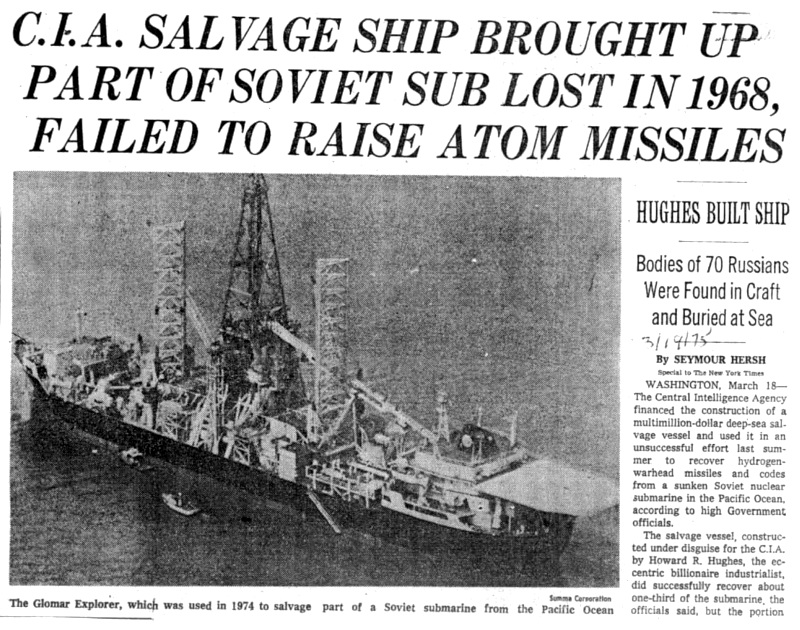

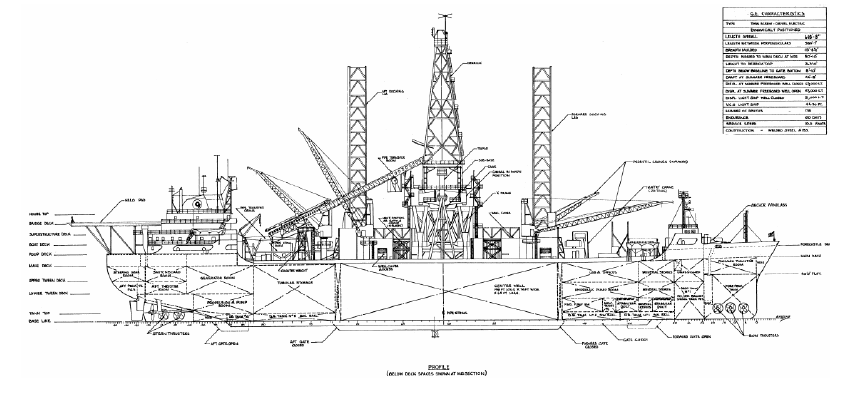

July 20, 2006 – Hughes Glomar Explorer recognized as Engineering Landmark

Former top-secret CIA ship Hughes Glomar Explorer, which became a pioneering petroleum industry drillship, was designated a mechanical engineering landmark during a Houston awards ceremony that included members of the original engineering team and the ship’s crew.

The American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) in 2006 proclaimed Hughes Glomar Explorer, “a technologically remarkable ship.” Illustration courtesy ASME.

The American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) designated the vessel, a technologically remarkable ship and historic mechanical engineering landmark. Built in 1972 as a clandestine Soviet submarine recovery project, the vessel’s design was “decades ahead of its time for working at extreme depths.” Modified and relaunched in 1998, the highly advanced Glomar Explorer became a pioneer of modern drillships.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: History Of Oil Well Drilling (2007); Drilling Technology in Nontechnical Language

(2012); The American Railroad Freight Car (1995); Early Days of Oil: A Pictorial History of the Beginnings of the Industry in Pennsylvania

(2000); Western Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage

(2008); Stages to Saturn: A Technological History of the Apollo/Saturn Launch Vehicles

(2003); Wildcatters: Texas Independent Oilmen

(1984); From the Rio Grande to the Arctic: The Story of the Richfield Oil Corporation

(1972); Kenai Peninsula Borough, Alaska

(2012); Texon: Legacy of an Oil Town, Images of America

(2011); Oil in West Texas and New Mexico

(1982); The CIA’s Greatest Covert Operation: Inside the Daring Mission to Recover a Nuclear-Armed Soviet Sub (2012); Project Azorian: The CIA and the Raising of the K-129 (2012). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.