by Bruce Wells | Feb 12, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

Reports of a “mineral tar” from the 1840s helped H.L. Hunt discover an oilfield a century later.

Swallowing “tar pills” supposedly had been curing ills since the mid-1800s, but Alabama’s petroleum industry officially began in 1944 with a Choctaw County well drilled by a well-known Texas wildcatter. On February 17, independent producer Haroldson Lafayette “H.L” Hunt completed his Jackson No. 1 well after discovering Alabama’s first oilfield.

H.L. Hunt had found success in the earliest Arkansas oilfields of the 1920s and even greater success in the East Texas oilfield of the 1930s. He now had revealed the Gilbertown oilfield of western Alabama, about 50 miles southeast of Meridian, Mississippi.

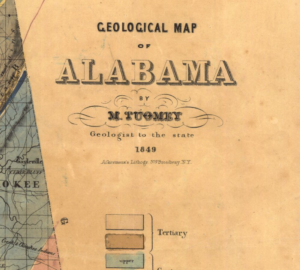

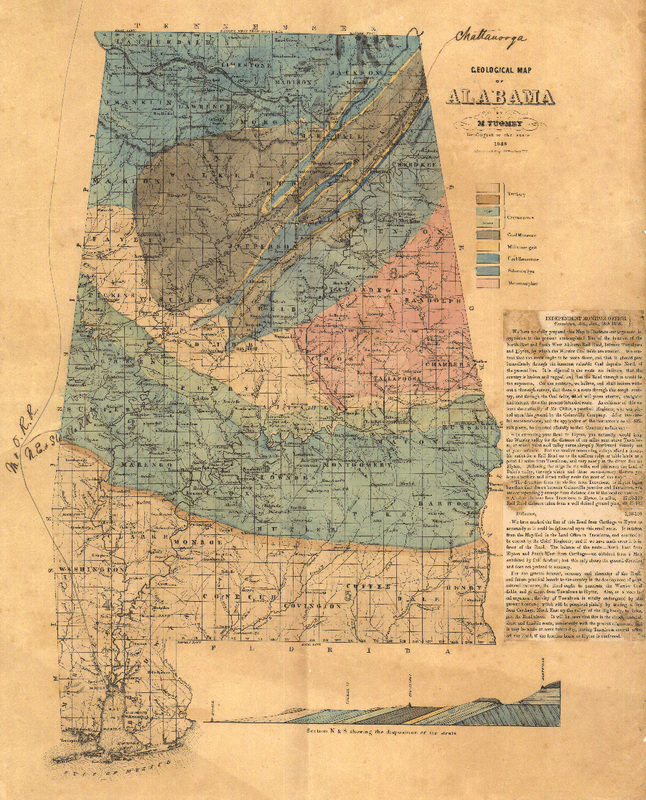

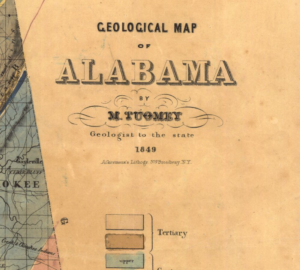

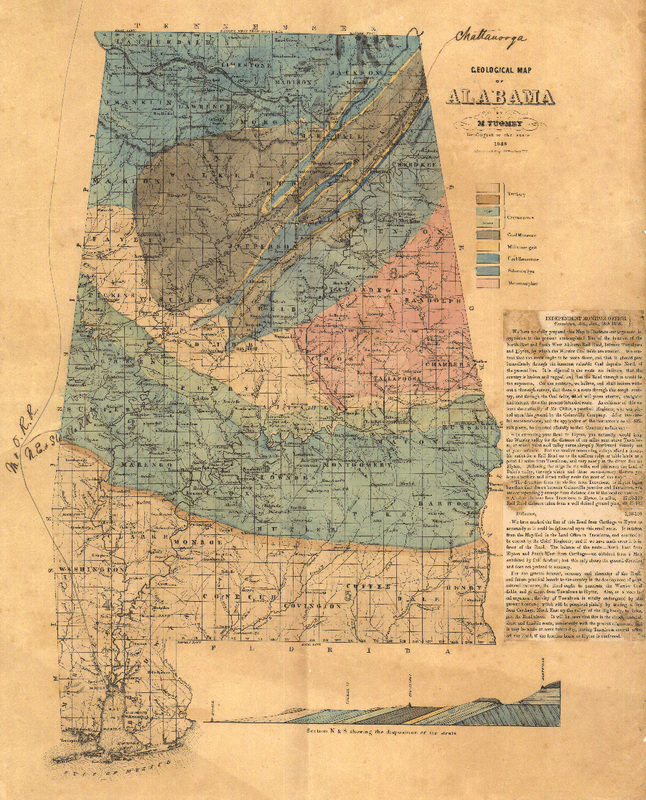

Geological Map of Alabama, printed in 1849 by Michael Tuomey, professor of geology, mineralogy and agricultural chemistry at the University of Alabama. Tuomey published his First Biennial Report of the Geology of Alabama in 1850. Map courtesy University of Alabama Libraries Special Collections.

Despite limited knowledge of the state’s geology, regions with oil and natural gas seeps had attracted interest as early as the mid-19th century. Before Hunt’s Choctaw County wildcat well, 350 dry holes had been drilled in Alabama.

Geologist and petroleum historian Ray Sorenson has investigated the earliest reports of petroleum in all producing states. By the early 2020s, his ongoing project documented the first signs of oil in the United States, Canada, and many parts of the world (see Exploring Earliest Signs of Oil).

In Alabama’s case, Sorenson uncovered an account by an early expert in the scientific field of geology. The first Alabama state geologist, Michael Tuomey, described reports of a “mineral tar,” and cited an 1840s account of finding natural oil seeps six miles from Oakville in Lawrence County.

With quantities of oil and water emerging from a crevice in limestone, Tuomey observed that “the tar, or bitumen, floats on the surface, a black film very cohesive and insoluble in water.”

The A.R. Jackson No. 1 well in 1944 revealed an Alabama oilfield near the Mississippi border. Photo courtesy Hunt Oil Company.

Similar to “Kentucky oil,” Alabama’s Lawrence County oil became popular for its medicinal qualities. Oil from the county was claimed to be “a known cure for Scrofula, Cancerous Sores, Rheumatism, Dyspepsia,” and other diseases.

“Patients visiting the Spring find the tar taken and swallowed as pills, the most efficient form of the remedy,” Tuomey quoted the observation from “Tar Spring of Lawrence” in the 1858 Second Biennial Report On the Geology of Alabama (published one year after his death).

Tuomey served as the state geologist of South Carolina from 1844 to 1847, and as the first state geologist of Alabama from 1848 until his death in 1857. His Geological Map of Alabama was printed in 1849.

In addition to oil, traces of natural gas were discovered in Alabama in the late 1880s, and by 1902, natural gas was being supplied to Huntsville and the town of Hazel Green, according to Alabama historian Alan Cockrell.

“In 1909, a small discovery by Eureka Oil and Gas at Fayette fueled that city’s streetlights for a time, but no natural gas was recovered anywhere in the state for several decades afterward,” he added. Learn about the earliest oilfield discoveries in other producing states in First Oil Discoveries.

Gilbertown Oil Discovery

According to Cockrell, Alabama’s oil and natural gas industry did not truly begin until H.L. Hunt of Dallas, Texas, drilled in Choctaw County near the Mississippi border and discovered the Gilbertown oilfield.

Concrete foundations are all that remains of Alabama’s first oil well, the A.R. Jackson Well No. 1, completed in 1944 near Gilbertown. Photo courtesy Explore Rural S.W. Alabama.

After five weeks of drilling, the well was completed on February 17, 1944, at 2,585 feet in the Selma chalk of the Upper Cretaceous. Hunt’s A.R. Jackson Well No. 1 two miles southwest of downtown Gilbertown had reached a total depth of 5,380 feet before being “plugged back” to its most productive oil-producing geologic formation.

H.L. Hunt’s first Alabama oil well produced just 30 barrels of oil a day, but launched the state’s petroleum industry. “The discovery of this well led to the creation of the State Oil and Gas Board of Alabama in 1945, and to the development and growth of the petroleum industry in Alabama,” notes an Alabama historic marker erected at the site.

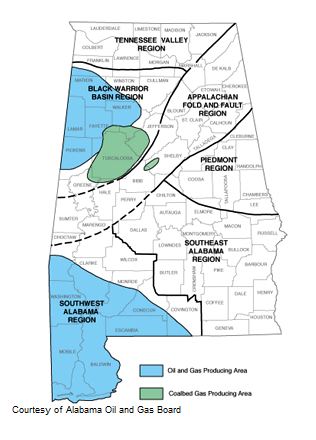

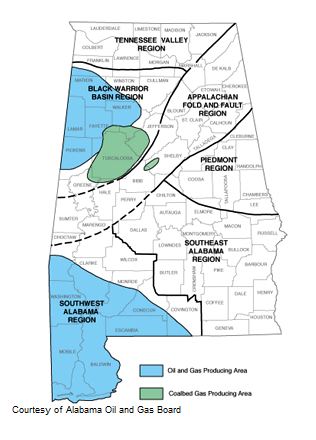

Deeper drilling led to more Alabama petroleum discoveries in the 1980s. Map courtesy Encyclopedia of Alabama.

The first oilfield would produce 15 million barrels of oil, “not a lot by modern standards but enough to make ‘oil fever’ spread rapidly,” Cockrell noted in “Oil and Gas Industry in Alabama” in 2008. The search for another oilfield took 11 more years.

The 1955 oil discovery at Citronelle, a town above a geologic salt dome, finally launched a new drilling boom; five new Alabama oilfields were discovered by 1967. Mobil Oil Company drilled Alabama’s first successful offshore natural gas well in 1981.

As production technologies advance, geologists believe opportunities exist in the “hard shales of the deep Black Warrior Basin beneath Pickens and Tuscaloosa counties and in the thick fractured shales of St. Clair and neighboring counties,” according to Cockrell.

By 2022, more than 17,500 oil and natural gas wells had been drilled in Alabama since the state’s first commercial oil discovery in 1944. According to the Washington, DC-based Independent Petroleum Association of America (IPAA), about 10 percent of the Alabama wells produced oil, 59 percent natural gas, and 30 percent (about 5,000 wells) were nonproductive.

Mapping Mineral Riches

From the journal Cartographic Perspectives of the North American Cartographic Information Society (NACIS):

Settlement of the newly available land enabled Alabama to move rapidly from being a part of the Mississippi Territory to its own Alabama Territory, and finally to statehood in 1819. The favorable climate and rich soil brought large plantations and slavery.

Appointed State Geologist of Alabama in 1848, Michael Tuomey served until his death in 1857.

Michael Tuomey (1805-1857), professor of geology at the University of Alabama in the 1840s, had attempted to lead Alabama’s economy away from slavery-based agriculture. In 1849, he produced the first survey of the state’s mineral wealth. His map Geological map of Alabama showed exactly where the state’s natural riches were located. The efforts of Tuomey and others were rejected, as were similar efforts in other southern states.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Lost Worlds in Alabama Rocks: A Guide (2000). Drilling Ahead, The Quest for Oil in the Deep South, 1945-2005 (2005). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society.

(2000). Drilling Ahead, The Quest for Oil in the Deep South, 1945-2005 (2005). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “First Alabama Oil Well.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/first-alabama-oil-well. Last Updated: February 12, 2025. Original Published Date: October 21, 2017.

by Bruce Wells | Feb 3, 2025 | Energy Education Resources

Growing oil demand challenged petroleum geologists, who organized a professional association.

As demand for petroleum grew during World War I, the science for finding oil and natural gas reserves remained obscure when a small group of geologists in 1917 organized what became the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG).

AAPG began as the Southwestern Association of Petroleum Geologists in Tulsa, Oklahoma, after about 90 geologists gathered at Henry Kendall College, now Tulsa University. They formed an association of earth scientists on February 10, 1917, “to which only reputable and recognized petroleum geologists are admitted.”

AAPG members maintain a professional business code.

Rapidly multiplying mechanized technologies of the “Great War” brought desperation to finding and producing vast supplies of oil. America entered the First War I two months after AAPG’s founding. An October 1917 giant oilfield discovery at Ranger, Texas, inspired a British War Cabinet member to declare, “The Allied cause floated to victory upon a wave of oil.”

Rock Hounds

In January 1918, the AAPG convention of in Oklahoma City reported 167 active members and 17 associate members. After adopting its present name one year after organizing at Henry Kendall College, the group issued its first technical bulletin, using papers and presentations delivered at the 1917 Tulsa meeting.

The professional “rock hounds” produced a mission statement that included promoting the science of geology, especially relating to oil and natural gas. The geologists also committed to encouraging “technology improvements in the methods of exploring for and exploiting these substances.”

AAPG was founded in Tulsa, Oklahoma, at Henry Kendall College — today’s Tulsa University.

AAPG also began publishing a bimonthly journal that remains among the most respected in the industry. The peer-reviewed Bulletin included papers written by leading geologists of the day.

With a subscription price of five dollars, the journal was distributed to members, university libraries, and other industry professionals.

Finding Faults and Anticlines

By 1920, one petroleum trade magazine — after complaining of the industry’s lack of skilled geologists — noted the “Association Grows in Membership and Influence; Combats the Fakers.”

The article praised AAPG professionalism and warned of “the large number of unscrupulous and inadequately prepared men who are attempting to do geological work.”

Similarly, the Oil Trade Journal praised AAPG for its commitment “to censor the great mass of inadequately prepared and sometimes unscrupulous reports on geological problems, which are wholly misleading to the industry.”

Perhaps the best known such fabrication is related to the men behind the 1930 East Texas oilfield discovery — a report entitled “Geological, Topographical And Petroliferous Survey, Portion of Rusk County, Texas, Made for C.M. Joiner by A.D. Lloyd, Geologist And Petroleum Engineer.”

Using very scientific terminology, A.D. Lloyd’s document described Rusk County geology — its anticlines, faults, and a salt dome — all features associated with substantial oil deposits…and all completely fictitious.

The fabrications nevertheless attracted investors, allowing Joiner and “Doc” Lloyd to drill a well that uncovered a massive oil field, still the largest conventional oil reservoir in the lower-48 states.

AAPG’s peer-reviewed journal first appeared in 1918, one year after the association’s first meeting in Tulsa.

Equally imaginative science came from Lloyd’s earlier descriptions of the “Yegua and Cook Mountain” formations and the thousands of seismographic registrations he ostensibly recorded. Lloyd, a former patent medicine salesman, and other self-proclaimed geologists, were the antithesis of the AAPG professional ethic.

In 1945, AAPG formed a “Committee on Boy Scout Literature” to assist the Boy Scouts of America in updating requirements for the “mining” badge, which had been awarded since 1911 (learn more in Merit Badge for Geology).

By 1953, AAPG membership had grown to more than 10,000 and a permanent headquarters building opened Tulsa. The association’s 2022 membership included about 40,000 members in 129 countries in the upstream energy industry, “who collaborate — and compete — to provide the means for humankind to thrive.”

The world’s largest professional geological society, a nonprofit organization, maintains a membership code to assure “integrity, business ethics, personal honor, and professional conduct.”

Oil Patch Historians

Longtime AAPG member Ray Sorenson, a Tulsa-based consulting geologist, has made numerous presentations about the history of petroleum. After publishing papers in leading academic journals, he adapted many of his contributions for the association’s 2007 Discovery Series, “First Impressions: Petroleum Geology at the Dawn of the North American Oil Industry.”

Further, Sorenson continued to research and collect a vast amount of material documenting the earliest signs of oil — worldwide references to hydrocarbons earlier that the 1859 first U.S. oil well drilled by Edwin Drake in Pennsylvania.

Drake expert and geologist and historian William Brice, professor emeritus at the University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown, in 2009 published Myth, Legend, Reality – Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry. His 661-page epic was researched and written as part of the U.S. petroleum industry’s 150th anniversary (learn more in Edwin Drake and his Oil Well),

As part if AAPG’s 2017 centennial events, geologist Robbie Rice Gries published Anomalies: Pioneering Women in Petroleum Geology 1917-2017. Researched with help from AAPG volunteers, her 405-page book includes contributors’ personal stories, written correspondence, and photographs dating back to the early 1900s.

The stories in Gries’ book should be read by every petroleum geologist, geophysicist and petroleum engineer, according to independent producer Marlan Downey, founder of Roxanna Oil Company. “Partly for the pleasure of the sprightly told adventures, partly for a sense of history, and, significantly, because it engenders a proper respect towards all women professionals, forging their unique way in a ‘man’s world.’”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Anomalies: Pioneering Women in Petroleum Geology 1917-2017 (2017); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975); Myth, Legend, Reality – Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (1991); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1936). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (1991); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1936). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “AAPG – Geology Pros since 1917.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL:https://aoghs.org/energy-education-resources/aapg-geology-pros-since-1917. Last Updated: February 4, 2025. Original Published Date: April 29, 2014.

(2000). Drilling Ahead, The Quest for Oil in the Deep South, 1945-2005 (2005). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society.