Legend of “Coal Oil Johnny”

The lucky life of John Steele and America’s earliest oil wealth.

John Washington Steele’s good fortune began on December 10, 1844, when Culbertson and Sarah McClintock adopted him as an infant. The McClintocks also adopted his sister Permelia, bringing both home to the farm along Oil Creek in Venango County, Pennsylvania.

Fifteen years later, the U.S. petroleum industry began with a 69.5-foot-deep oil discovery at nearby Titusville, the first oil well drilled commercially for distilling into kerosene (also called coal oil).

Pennsylvania petroleum reserves revealed at Oil Creek made the widow McClintock a fortune in royalties. When she died in a kitchen fire in 1864, Mrs. McClintock left her oil wealth to her only surviving child, Johnny, who inherited $24,500 at age 20.

Johnny also inherited his mother’s 200-acre farm along Oil Creek between the now Rynd Farm and the small community of Rouseville, south of 15-miles Titusville. The farm already included 20 producing oil wells yielding $2,800 in royalties every day.

Rouseville was where future muckraking journalist Ida Minerva Tarbell (1857-1944) lived in 1861, when a gushing well erupted into flames — resulting in an early petroleum industry tragedy (see Rouseville 1861 Oil Well Fire).

Legendary Extravagance

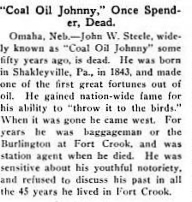

“Coal Oil Johnny” Steele would earn his famous name in 1865 — after less than one year of extravagance, according to the New York Times.

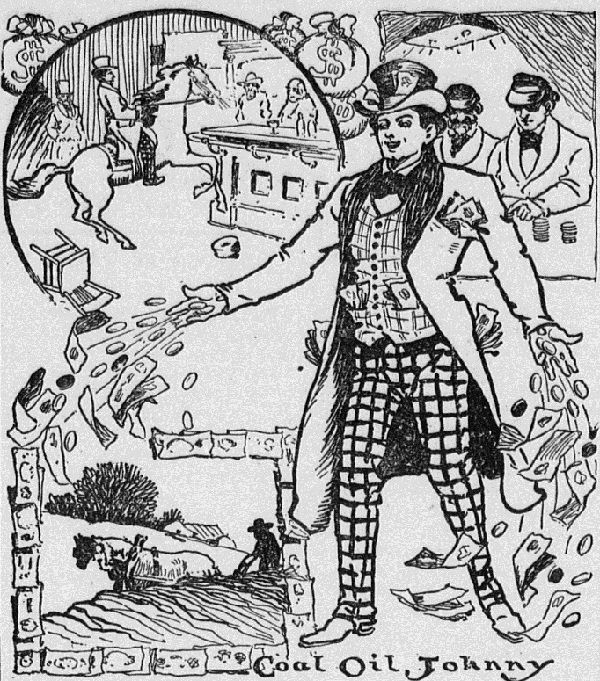

“In his day, Steele was the greatest spender the world had ever known,” the newspaper proclaimed. “He threw away $3,000,000 in less than a year.”

Philadelphia journalists coined the name “Coal Oil Johnny” for him, reportedly because of his attachment to a custom carriage that had black oil derricks spouting dollar symbols painted on its red doors. He later confessed in his autobiography:

I spent my money foolishly, recklessly, wickedly, gave it away without excuse; threw dollars to street urchins to see them scramble; tipped waiters with five and ten dollar bills; was intoxicated most of the time, and kept the crowd surrounding me usually in the same condition.

“Before J.R. Ewing, or the Beverly Hillbillies, or even John D. Rockefeller, there was Coal Oil Johnny,” noted a 2010 article in The Atlantic.

Such wealth could not last forever, but the rise and fall of Coal Oil Johnny, who died in modest circumstances in 1920 at age 76, has lingered in America’s petroleum history.

In 2010, The Atlantic magazine published “The Legend of Coal Oil Johnny, America’s Great Forgotten Parable,” an article sympathetic to his riches-to-rags story. It describes the country’s fascination with the earliest economic booms brought by “black gold” discoveries in Pennsylvania.

“Before J.R. Ewing, or the Beverly Hillbillies, or even John D. Rockefeller, there was Coal Oil Johnny,” noted the October 18 feature story. “He was the first great cautionary tale of the oil age — and his name would resound in popular culture for more than half a century after he made and lost his fortune in the 1860s.”

Refurbished boyhood home of “Coal Oil Johnny” at Oil Creek State Park (and train station) north of Rouseville, Pennsylvania. Photo by Bruce Wells.

For generations after the peak of his career, Johnny was still so famous that any major oil strike — especially the January 1901 gusher at Spindletop Hill in Beaumont, Texas — “brought his tales back to people’s lips,” noted the magazine article, citing Brian Black, a historian at Pennsylvania State University.

“It was wealth from nowhere,” Black explained. “Somebody like that was coming in without any opportunity or wealth and suddenly has a transforming moment. That’s the magic and it transfers right through to the Beverly Hillbillies and the rest of the mythology.”

“Coal Oil Johnny” was a legend, and like all legends, “he became a stand-in for a constellation of people, things, ideas, feelings and morals – in this case, about oil wealth and how it works,” he added.

“He made and lost this huge fortune – and yet he didn’t go crazy or do anything terrible. Instead, he ended up living a regular, content life, mostly as a railroad agent in Nebraska,” the 2010 Atlantic article concluded. “Surely there’s a lesson in that for the millions who’ve lost everything in the housing boom and bust.”

John Washington Steele’s Venango County home, relocated and restored by Pennsylvania’s Oil Region Alliance of Business, Industry & Tourism, stands today in Oil Creek State Park, just off Route 8, north of Rouseville.

On Route 8 south of Rouseville is the still-producing McClintock No. 1 oil well. “This is the oldest well in the world that is still producing oil at its original depth,” proclaims the Alliance. “Souvenir bottles of crude oil from McClintock Well Number One are available at the Drake Well Museum, outside Titusville.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Legend of Coal Oil Johnny (2007); Cherry Run Valley: Plumer, Pithole, and Oil City, Pennsylvania, Images of America (2000); Western Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage (2008). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: Legend of “Coal Oil Johnny.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/legend-of-coal-oil-johnny. Last Updated: December 4, 2025. Original Published Date: April 29, 2013.