by Bruce Wells | Nov 28, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

Rise and fall of an infamous Pennsylvania boomtown.

As the Civil War ended, oil discoveries at Pithole Creek in Pennsylvania created a headline-making boomtown for the young petroleum industry. As wells reached deeper into geological formations, the first gushers arrived — adding to “black gold” fever sweeping the country.

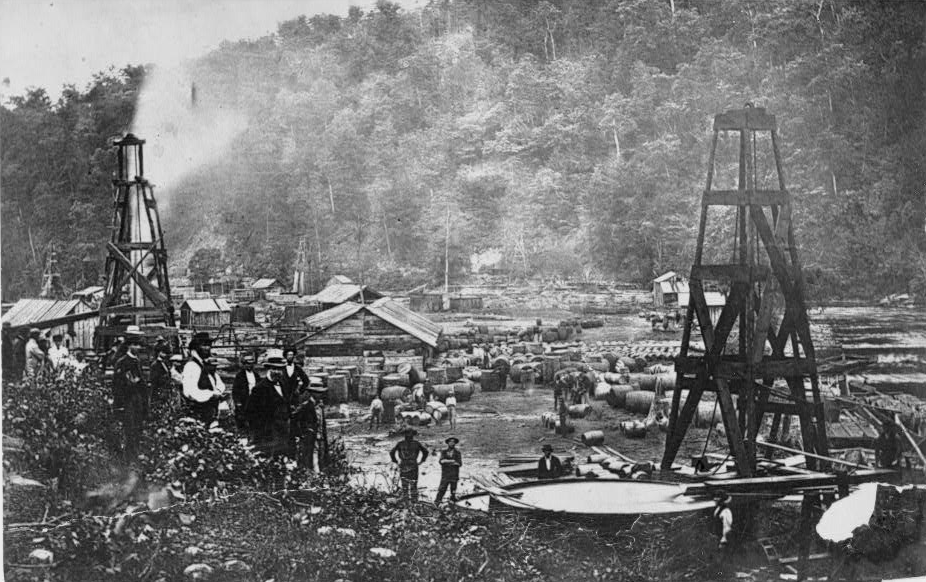

America’s oil production began in 1859 when Edwin L. Drake completed the first commercial well at Titusville, Pennsylvania. Drilled near natural oil seeps, his oilfield discovery at a depth of 69.5 feet led to a rush of exploration in the remote Allegheny River Valley.

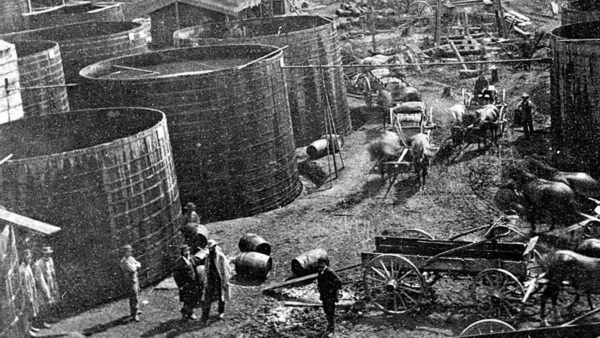

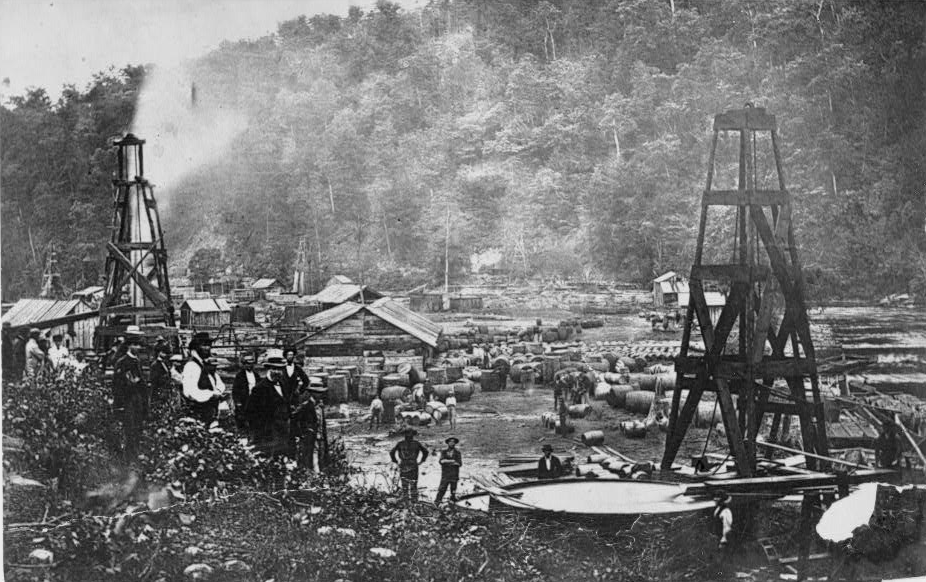

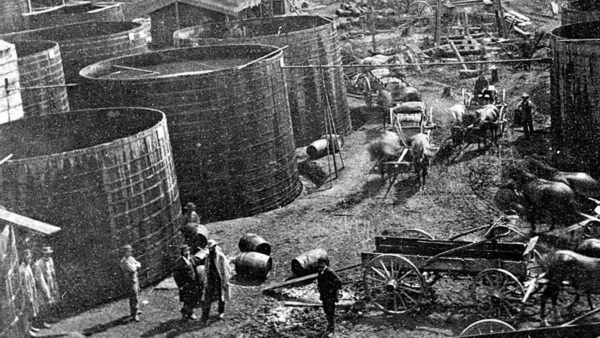

The new petroleum industry’s transportation infrastructure struggled as oil tanks crowded Pithole, Pennsylvania. In 1865, the first oil pipeline linked an oil well to a railroad station about five miles away. Photo by the “Oil Creek Artist,” John Mather, courtesy Drake Well Museum.

In 1864, businessman Ian Frazier found success along Cherry Creek, another small watercourse with signs of oil. After making a quick $250,000, Frazier looked for another opportunity for providing oil to new Pittsburgh refineries making kerosene for lamps.

Frazier hired a diviner to search along Pithole Creek, which smelled like “sulfur and brimstone,” according to historian Douglas Wayne Houck. “He went to the creek and followed the diviner around until the forked twig dipped, pointing to a specific spot on the ground,” Houck noted in 2014.

Although exploration techniques would improve, the science of petroleum geology was still in the future. Oil companies (and soon natural gas) had already begun drilling the “dry holes.”

Gusher at Pithole Creek

The first well of Ian Frazier’s United States Oil Company found no oil. A second well — drilled using the same steam-powered, cable-tool technology — erupted spectacularly on January 7, 1865, producing 650 barrels of oil a day. The Frazier well, the first U.S. oil gusher, brought a flood of drillers and speculators to Pithole Creek.

Two more wells erupted black geysers on January 17 and January 19, each flowing at about 800 barrels of oil a day (the invention of a practical blowout preventer was still half a century away). United States Oil Company subdivided its property and began selling lots for $3,000 per half-acre plot.

The Titusville Herald proclaimed Pithole as having “probably the most productive wells in the oil region of Pennsylvania, Houck explained in his Energy & Light in Nineteenth-Century Western New York. Fortunes were being made and lost in the oil regions (see the Legend of “Coal Oil Johnny”).

As the news spread through Venango County, “everyone came to the Pithole area to try their luck,” noted one reporter. Many were Confederate and Union war veterans. And as more successful wells came in, about 3,000 teamsters rushed to Pithole to haul out the rapidly multiplying barrels of oil.

Managed by the Drake Well Museum, the Pithole Visitors Center includes a diorama of the vanished town. Photo by Bruce Wells.

There were many reasons behind the Pithole oil boom, including a flood of paper money at the end of the Civil War. Returning Union veterans had currency and were eager to invest — especially after reading newspaper articles about oil gushers and boomtowns. Thousands of veterans also wanted jobs after long months on army pay.

By May 1865, the town was home to 57 hotels, many shops, and its own daily newspaper. It had the third busiest post office in Pennsylvania — handling 5,500 pieces of mail a day.

Pithole’s Lady Macbeth

In December 1865, Shakespearean tragedienne Miss Eloise Bridges appeared as Lady Macbeth in America’s first famously notorious oil boomtown.

Shakespearean tragedienne Eloise Bridges appeared on the Pithole stage in 1865.

Bridges appeared at Murphy’s Theater, the biggest building in a town of more than 30,000 teamsters, coopers, lease-traders, roughnecks, and merchants. Three stories high, the building had 1,100 seats, a 40-foot stage, an orchestra, and chandelier lighting by Tiffany.

Bridges was the acclaimed darling of the Pithole stage. Eight months after she departed for new engagements in Ohio, the oilfield at Pithole ran dry; the most famous U.S. boomtown collapsed into empty streets and abandoned buildings.

Pennsylvania oil region visitors today walk the grassy streets of the first oil boom’s ghost town.

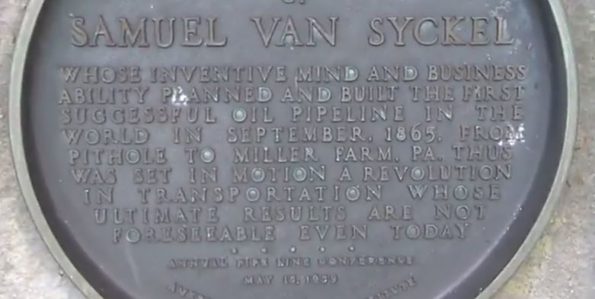

First Oil Pipeline

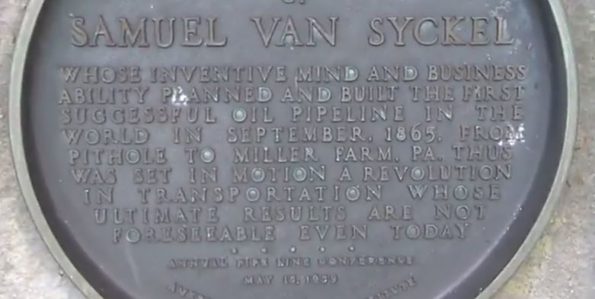

As Pithole oil tanks overflowed (and tank fires from accidents and lightning strikes increased), petroleum shipper Samuel Van Syckel conceived an infrastructure solution that became an engineering milestone.

In 1865, his newly formed Oil Transportation Association put into service a two-inch iron line linking the Frazier well to the Miller Farm Oil Creek Railroad Station, about five miles away.

The American Petroleum Institute in 1959 dedicated a plaque on the grounds of the Drake Well Museum as part of the U.S. oil centennial.

“The day that the Van Syckel pipe-line began to run oil a revolution began in the business. After the Drake well it is the most important event in the history of the Oil Regions,” declared Ida Tarbell about the technology in her 1904 book, History of the Standard Oil Company.

Widely known as a known magazine journalist and a Lincoln biographer, Tarbell grew up in the area. Her family lived in Rouseville in 1861 when a gushing well erupted into flames — an early oilfield tragedy.

With 15-foot welded joints and three 10-horsepower Reed and Cogswell steam pumps, the pipeline transported 80 barrels of oil per hour — the equivalent of 300 teamster wagons working for 10 hours. Convinced their livelihood was threatened, teamsters attempted to sabotage the oil pipeline until armed guards intervened.

Unfortunately for Van Syckel, Pithole oil storage tanks frequently caught fire even as the Frazier well production began to decline. Other wells were beginning to run dry when, in 1866, fires spread out of control and burned 30 buildings, 30 oil wells, and 20,000 barrels of oil.

Pithole City

“Pithole’s days were numbered,” concluded historian Houck about the fire, which was documented by early oilfield photographer John Mather. “Buildings were taken down and carted off. A few people hung around until 1867.”

Visitors walk the grassy paths of Pithole’s former streets and see artifacts, including antique steam boilers. Volunteers “mow the streets.” Photo by Bruce Wells.

From beginning to end, America’s famous oil boomtown had lasted about 500 days. Pithole was added to the National Register of Historic Places on March 20, 1973.

A visitors center added in 1975 contains exhibits, including a scale model of the city at its peak and a small theater. Volunteers “mow the streets” on the hillside so that tourists can stroll where the petroleum boomtown once flourished.

“Pithole City is known in the Pennsylvania oil region as the oil boomtown that vanished as quickly as it appeared,” notes the Drake Well Museum, which manages Historic Pithole City. Among the region’s earliest and most infamous investors was John Wilkes Booth (see the Dramatic Oil Company).

Oil Town Aero Views

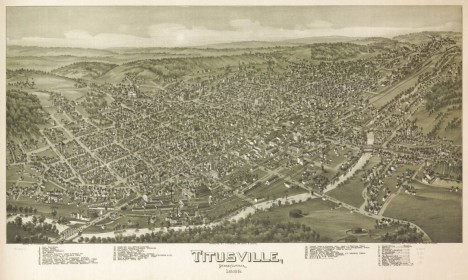

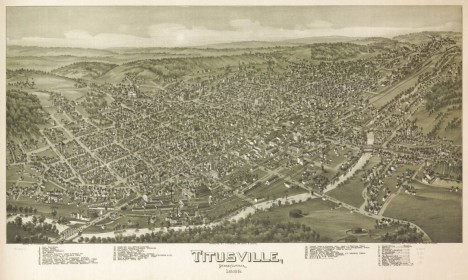

During the late 19th century, “bird’s-eye views” became a widely popular way to map U.S. cities and towns. Cartographer Thaddeus Mortimer Fowler created many of the best panoramic maps that he also called “aero views.”

The wealthy Pennsylvania oil regions attracted the attention of Fowler, who in 1885 moved his family to Morrisville, where he worked for the next 25 years.

An 1896 Pennsylvania “aero view” map by Thaddeus M. Fowler, courtesy Library of Congress.

Fowler drew maps of Titusville, Oil City, and many petroleum-related boomtowns in West Virginia, Ohio — and Texas, where he created dozens of views of cities from 1890 to 1891.

But by far, most of the Fowler maps feature Pennsylvania cities between 1872 and 1922. There are 250 examples of his work in the collection of the Library of Congress. Learn more in Oil Town “Aero Views.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Energy & Light in Nineteenth-Century Western New York (2014); Cherry Run Valley: Plumer, Pithole, and Oil City, Pennsylvania, Images of America (2000); The Legend of Coal Oil Johnny

(2000); The Legend of Coal Oil Johnny (2007); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2007); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Oil Boom at Pithole Creek.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/pithole-creek/. Last Updated: November 29, 2025. Original Published Date: March 15, 2014.

by Bruce Wells | Feb 17, 2025 | This Week in Petroleum History

February 17, 1902 – Lufkin Industries founded in East Texas –

The Lufkin Foundry and Machine Company was founded in Lufkin, Texas, as a repair shop for railroad and sawmill machinery. When the pine region’s timber supplies began to dwindle, the company discovered new opportunities in the burgeoning oilfields following the 1901 discovery at Spindletop Hill.

A Lufkin counter-balanced oil pump near Beaumont, Texas, in 2003. Photo by Bruce Wells.

Inventor Walter C. Trout was working for this East Texas company in 1925 when he came up with a new idea for pumping oil. His design would become an oilfield icon known by many names — nodding donkey, grasshopper, horse-head, thirsty bird, and pump jack, among others.

By the end of 1925, a prototype of Trout’s pumping unit was installed on a Humble Oil and Refining Company well near Hull, Texas. “The well was perfectly balanced, but even with this result, it was such a funny looking, odd thing that it was subject to ridicule and criticism,” Trout explained.

Learn more in All Pumped Up – Oilfield Technology.

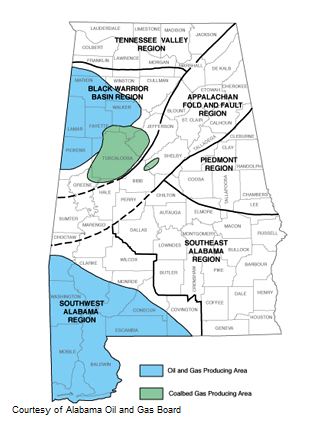

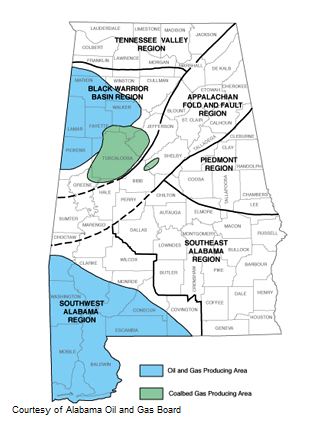

February 17, 1944 – H.L. Hunt discovers First Alabama Oilfield

Alabama’s first oilfield was discovered in Choctaw County when independent producer H.L. Hunt of Dallas, Texas, drilled the No. 1 Jackson well. Hunt’s 1944 wildcat well revealed the Gilbertown oilfield. Prior to this discovery, 350 dry holes had been drilled in the state.

Alabama’s major petroleum-producing regions are in the west. Map courtesy Encyclopedia of Alabama.

According to research by petroleum geologist Ray Sorenson, an 1858 report first noted Alabama natural oil seeps about six miles from Oakville in Lawrence County (see Exploring Earliest Signs of Oil). Hunt’s discovery well was drilled in Choctaw County, where he revealed the Gilbertown oilfield at a depth of 3,700 feet.

Although it took 11 years for another oilfield discovery, new technologies and deeper wells in the late 1980s led to the prolific Little Cedar Creek and Brooklyn fields. By the mid-2000s, geologic assessments were underway for the potential of the shales of St. Clair and neighboring counties.

Learn more in First Alabama Oil Well.

February 19, 1863 – First Pipeline Attempt to link Oilfield to Refinery

With teamsters dominating oil transportation in Pennsylvania, independent producer James L. Hutchings designed and constructed a pipeline to transport oil from a well on a farm at Oil Creek to a refinery 2.5 miles away. He had patented a rotary pump, which he used for moving the oil through two-inch piping from the Tarr Farm to the Humboldt Refinery at Oil City. His pumps worked, but the cast-iron pipeline proved impractical when the joints leaked.

The 1863 pipeline attempt began from an oil well on the Tarr Farm (above) north of Oil City, Pennsylvania. December 1861 photograph by John Mather courtesy Library of Congress.

Hutchings’ concept of driving fluids with a rotary pump brought a key innovation for pipeline construction. In 1865, Samuel Van Syckel would break the teamsters’ monopoly by constructing a wrought iron pipeline with threaded joints that could transport 2,000 barrels of oil a day more than five miles — the first practical oil pipeline.

“It kind of shows you how multiple failures lead to success,” noted pipeline engineer Claudia Farrell in 2002. “The idea of driving fluids with a rotary pump sparked an innovation in the pipeline industry.”

February 20, 1959 – First LNG Tanker arrives in England

After a 27-day voyage from a processing facility just south of Lake Charles, Louisiana, the world’s first liquefied natural gas tanker arrived at Canvey Island in England’s Thames estuary, the world’s first LNG terminal. The experimental Methane Pioneer demonstrated that large quantities of LNG could be transported safely across the ocean.

The world’s first liquefied natural gas tanker, the Methane Pioneer, was a converted World War II Liberty freighter.

The first-of-its-kind vessel, a converted World War II Liberty freighter, included five 7,000-barrel aluminum tanks supported by balsa wood and insulated with plywood and urethane. Owned by Comstock Liquid Methane Corporation, the 340-foot ship kept its methane cargo refrigerated to minus 285 degrees Fahrenheit. In June 1964, the first purpose-built commercial LNG carrier — the nine LNG tank, 618-foot Methane Princess — began regular delivery to the same Canvey Island port.

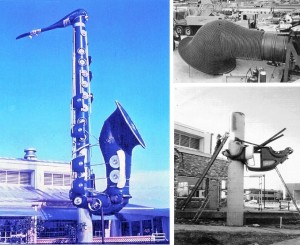

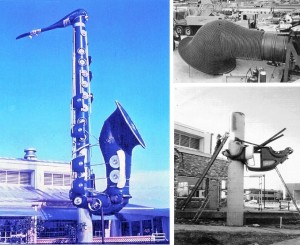

February 20, 1993 – Oil Pipe Saxophone erected in Houston

Petroleum pipelines became a work of art when offbeat Texas sculptor Bob “Daddy-O” Wade debuted his blue, 70-foot saxophone at the opening of Billy Blues Bar & Grill on Houston’s west side.

Petroleum pipeline segments contributed to a 1993 saxophone sculpture for Billy Blues Bar & Grill in Houston, Texas.

Wade transformed two 48-inch-wide pipes into the free-standing sculpture, adding an upside-down Volkswagen, chrome hubcaps, beer kegs, and assorted parts to complete his blue creation. After much debate, the Houston City Council deemed the oilfield pipeline saxophone to be art rather than signage. The Fort Worth Star-Telegram described Wade as a “connoisseur of Southwestern kitsch.”

Learn more in “Smokesax” Art has Pipeline Heart.

February 21, 1887 – Refining Process brings Riches to Rockefeller

Mining engineer and chemist Herman Frasch applied to patent a new process for eliminating sulfur from “skunk-bearing oils.” The former employee of Standard Oil of New Jersey was quickly rehired by John D. Rockefeller, who owned oilfields near Lima, Ohio, that produced a thick, sulfurous oil.

Standard Oil Company, which had accumulated a 40-million barrel stockpile of the inexpensive, sour “Lima oil,” bought Frasch’s patent for its copper-oxide refining process to “sweeten” the oil.

Herman Frasch (1851-1914), inventor of a key refinery process, by 1911 earned more wealth as the “Sulfur King.”

By the early 1890s, Standard Oil’s giant Whiting oil refinery east of Chicago was producing odorless kerosene from desulfurized oil, making Rockefeller another fortune.

Paid in Standard Oil shares and becoming very wealthy, Frasch moved to Louisiana — where the chemist made yet another fortune. By 1911, he was known as the “Sulfur King” after inventing a method for extracting sulfur from underground deposits by injecting superheated water into wells.

February 22, 1923 – First Carbon Black Factory in Texas

Texas granted its first permit for a carbon black factory to J.W. Hassel & Associates in Stephens County after scientists discovered carbon black increased the durability of rubber used in tires. Produced by the controlled combustion of petroleum products, carbon black could be used in many rubber products.

Early cars like the 1919 Pierce-Arrow had white rubber tires until B.F. Goodrich discovered carbon black improved durability. Photo courtesy Peter Valdes-Dapena.

Automobile tires were white until B.F. Goodrich Company in 1910 discovered that adding carbon black to the vulcanizing process improved strength and durability. An early Goodrich supplier was crayon manufacturer Binney & Smith Company (see Carbon Black and Oilfield Crayons).

February 23, 1906 – Flaming Kansas Gas Well makes Headlines

A small town in southeastern Kansas found itself making headlines when a natural gas well erupted into flames after a lightning strike. The 150-foot burning tower could be seen at night for 35 miles.

Kansas oilfield workers struggled to extinguish this 1906 well at Caney. Photo courtesy Jeff Spencer.

Drilled by the New York Oil and Gas Company, the well became a tourist attraction. Newspapers as far away as Los Angeles regularly updated their readers as technologies of the day struggled to extinguish the highly pressurized well, “which defied the ingenuity of man to subdue its roaring flames.”

A Denver publishing company sold postcards of the blazing Caney well, which took five weeks to smother using a specially designed and fabricated steel hood.

Learn more in Kansas Gas Well Fire.

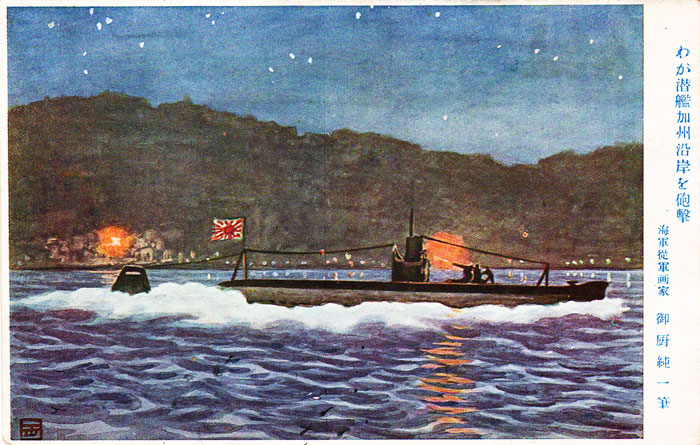

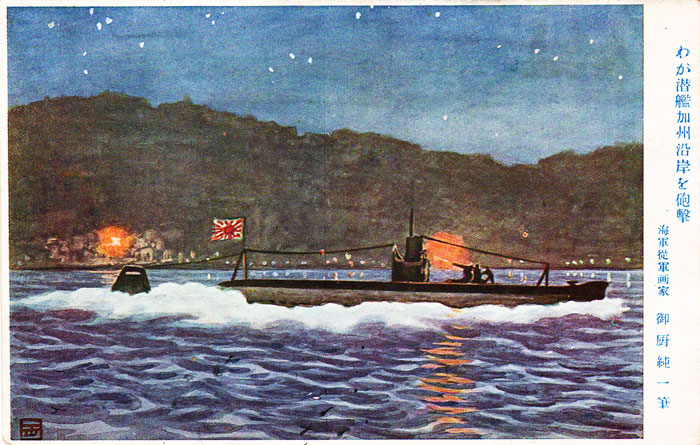

February 23, 1942 – Japanese Submarine shells California Oil Refinery

Less than three months after the start of World War II, a Japanese submarine attacked a refinery and oilfield near Los Angeles. The shelling caused little damage but created the largest mass sighting of UFOs ever in American history.

A rare Japanese postcard depicting the 1942 shelling of a California oil refinery by Imperial Navy submarine I-17. Image courtesy John Geoghegan.

Imperial Japanese Navy submarine I-17 fired armor-piercing shells at the Bankline Oil Company refinery in Ellwood City, California. The shelling north of Santa Barbara continued for 20 minutes before I-17 escaped into the night. The first Axis attack on the continental United States resulted in UFO sightings, mass hysteria and the “Battle of Los Angeles.”

Learn more in Japanese Sub attacks Oilfield.

_______________________

Recommended Reading:

Lufkin, from sawdust to oil: A history of Lufkin Industries, Inc. (1982); Lost Worlds in Alabama Rocks: A Guide

(1982); Lost Worlds in Alabama Rocks: A Guide (2000); Petrolia: The Landscape of America’s First Oil Boom (2003); Natural Gas: Fuel for the 21st Century

(2000); Petrolia: The Landscape of America’s First Oil Boom (2003); Natural Gas: Fuel for the 21st Century (2015); Daddy-O’s Book of Big-Ass Art (2020); Herman Frasch — The Sulphur King (2013); The B.F. Goodrich Story Of Creative Enterprise 1870-1952

(2015); Daddy-O’s Book of Big-Ass Art (2020); Herman Frasch — The Sulphur King (2013); The B.F. Goodrich Story Of Creative Enterprise 1870-1952 (2010); Caney, Kansas: The Big Gas City

(2010); Caney, Kansas: The Big Gas City (1985); The Battle of Los Angeles, 1942: The Mystery Air Raid

(1985); The Battle of Los Angeles, 1942: The Mystery Air Raid (2010). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2010). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

(2000); The Legend of Coal Oil Johnny

(2007); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.