by Bruce Wells | Jan 20, 2026 | Petroleum Pioneers

When a Fort Worth independent producer completed a remote wildcat well in East Texas on January 26, 1931, the well revealed the true extent of an oilfield discovered months earlier and many miles away.

As the Great Depression worsened and East Texas farmers struggled to survive, W.A. “Monty” Moncrief and two partners drilled the Lathrop No. 1 well in Gregg County. When completed in 1931, their well produced 320 barrels of oil per hour from a depth of 3,587 feet.

Far from what earlier were thought to be two oilfield discoveries — this third well producing 7,680 barrels a day revealed a “Black Giant.”

A circa 1960 photograph of W.A. “Monty” Moncrief and his son “Tex” in Fort Worth’s Moncrief Building.

Moncrief, who had worked for Marland Oil Company in Fort Worth after returning from World War I, drilled in a region (and at a depth) where few geologists thought petroleum production a possibility. He and fellow independent operators John Ferrell and Eddie Showers thought otherwise.

The third East Texas well was completed 25 miles north of Rusk County’s already famous October 1930 Daisy Bradford No. 3 well drilled by Columbus Marion “Dad” Joiner northwest of Henderson (and southeast New London, site of a tragic 1937 school explosion).

Moncrief’s oil discovery came 15 miles north of the Lou Della Crim No. 1 well, drilled three days after Christmas, on “Mama” Crim’s farm about nine miles from the Joiner well. At first, the distances between these “wildcat” discoveries convinced geologists, petroleum engineers (and experts at the large oil companies) the wells were small, separate oilfields. They were wrong.

Three Wells, One Giant Oilfield

To the delight of other independent producers and many small, struggling farmers, Moncrief’s Lathrop discovery showed that the three wells were part of a single petroleum-producing field. Further development and a forest of steel derricks revealed the northernmost extension of the 130,000-acre East Texas oilfield.

The history of the petroleum industry’s gigantic oilfield has been preserved at the East Texas Oil Museum, which opened at Kilgore College in 1980. Joe White, the museum’s founding director, created exhibit spaces for the “authentic recreation of the oil discoveries and production in the early 1930s in the largest oilfield inside U.S. boundaries.”

After more than half a century of major discoveries, William Alvin “Monty” Moncrief died in 1986. His legacy has extended beyond his good fortune in East Texas.

The family exploration business established by Moncrief in 1929 would be led by sons W.A. “Tex” Moncrief Jr. and C.B. “Charlie” Moncrief, who grew up in the exploration business. In 2010, Forbes reported that 94-year-old “Tex” made “perhaps the biggest find of his life” by discovering an offshore field of about six trillion cubic feet of gas.

Moncrief Philanthropy

Hospitals in communities near the senior Moncrief’s nationwide discoveries, including a giant oilfield in Jay, Florida, revealed in 1970, and another in Louisiana, have benefited from his drilling acumen.

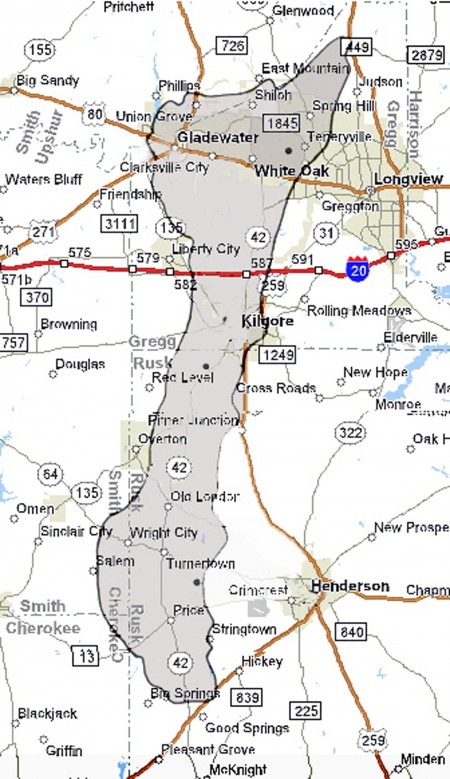

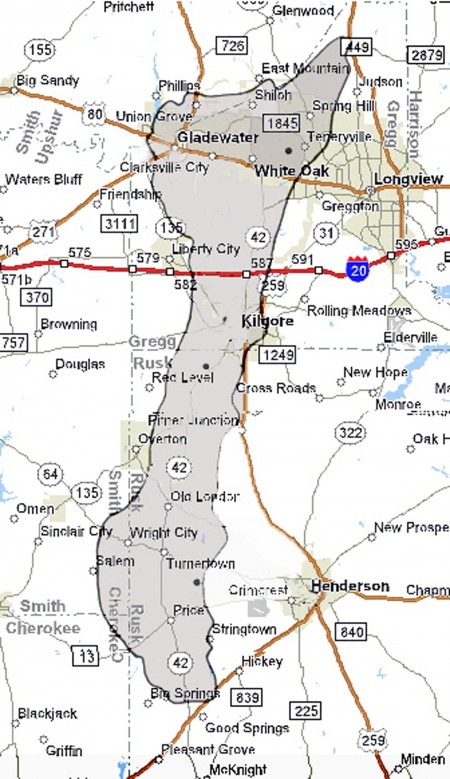

The 130,000-acre East Texas oilfield became the largest in the contiguous United States in 1930.

Moncrief and his wife established the William A. and Elizabeth B. Moncrief Foundation and the Moncrief Radiation Center in Fort Worth, as well as the Moncrief Annex of the All Saints Hospital. Buildings in their honor have been erected at Texas Christian University, All Saints School, and Fort Worth Country Day School.

Dr. Daniel Podolsky in 2013 presented W.A. “Tex” Moncrief Jr. with a framed image of the new Moncrief Cancer Institute at the Fort Worth facility’s dedication ceremony.

Supported throughout the 1960s and 1970s by the Moncrief family, Fort Worth’s original Cancer Center, known as the Radiation Center, was founded in 1958 as one of the nation’s first community radiation facilities.

In 2013, the $22 million Moncrief Cancer Institute was dedicated during a ceremony attended by “Tex” Moncrief Jr. “One man’s vision for a place that would make life better for cancer survivors is now a reality in Fort Worth,” noted one reporter at the dedication of the 3.4-acre facility at 400 W. Magnolia Avenue.

Small investments from hopeful Texas farmers brought historic results — and prosperity to Kilgore, Longview, and Tyler during the Great Depression. Kilgore annually celebrates its oil heritage.

Early Days in Oklahoma

Born in Sulphur Springs, Texas, on August 25, 1895, Moncrief grew up in Checotah, Oklahoma, where his family moved when he was five. Checotah was the town where Moncrief attended high school, taking typing and shorthand — and excelling to the point that he became a court reporter in Eufaula, Oklahoma.

To get an education, Moncrief saved $150 to enroll at the University of Oklahoma at Norman, where he worked in the registrar’s office. He became “Monty” after his initiation into the Sigma Chi fraternity.

During World War I, Moncrief volunteered and joined the U.S. Cavalry. He was sent to officer training camp in Little Rock, Arkansas, where he met and, six months later, married Mary Elizabeth Bright on May 28, 1918. Sent to France, Moncrief saw no combat thanks to the Armistice being signed before his battalion reached the front.

After the war, Moncrief returned to Oklahoma, where he found work at Marland Oil, first in its accounting department and later in its land office. When Marland opened offices in Fort Worth in the late 1920s, Moncrief was promoted to vice president for the new division.

In 1929, Moncrief would strike out on his own as an independent operator. He teamed up with John Ferrell and Eddie Showers, and they bought leases where they ultimately drilled the successful F.K. Lathrop No. 1 well.

C.M. “Dad” Joiner’s partner, the 300-pound self-taught geologist A.D. “Doc” Lloyd, had predicted the field would be four to ten miles wide and 50 to 50 miles long, according to Moncrief, interviewed in 1985 for Wildcatter: A Story of Texas Oil.

“Of course, everyone at the time thought he was nuts, including me,” the Texas wildcatter added. Also interviewed, museum founder Joe White said Lloyd’s assessment predicted the Woodbine sands at a depth of 3,550 — about two thousand feet shallower than major oil company geologists believed.

Moncrief’s Lathrop January 1931 wildcat well, which produced from the Woodbine formation at a depth of 3,587 feet, proved the oilfield stretched 42 miles long and up to eight miles wide — the largest in the lower 48 states.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Black Giant: A History of the East Texas Oil Field and Oil Industry Skulduggery & Trivia (2003); Early Texas Oil: A Photographic History, 1866-1936

(2003); Early Texas Oil: A Photographic History, 1866-1936 (2000). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2000). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2026 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Moncrief makes East Texas History.” Authors: B.A. and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/moncrief-oil. Last Updated: January 19, 2026. Original Published Date: January 25, 2015.

by Bruce Wells | Sep 29, 2025 | This Week in Petroleum History

September 30, 2006 – Roughnecks Statue dedicated at Signal Hill –

A bronze Tribute to the Roughnecks statue was dedicated near the Alamitos No. 1 well, which in 1921 revealed California’s prolific Long Beach oilfield 20 miles south of Los Angeles.

Signal Hill once had so many derricks people called it Porcupine Hill. The city of Long Beach is visible in the distance from the “Tribute to the Roughnecks” statue by Cindy Jackson.

The statue by Cindy Jackson has since commemorated the Signal Hill Oil Boom, serving as “a tribute to the petroleum pioneers for their success here, a success which has, by aiding in the growth and expansion of the petroleum industry, contributed so much to the welfare of mankind.”

October 1, 1908 – Ford Motor Company produces First Model T

The first production Ford Model T rolled off the assembly line in Detroit. Between 1908 and 1927, Ford built about 15 million more, each fueled by inexpensive gasoline. The popularity of the Model T was timely for the U.S. petroleum industry, which faced falling demand for kerosene as consumers switched to electric lighting.

Ford Model T tires were white until 1910, when the petroleum product carbon black was added to improve durability.

New major oilfield discoveries, especially the 1901 “Lucas Gusher” at Spindletop Hill near Beaumont, Texas, helped meet growing demand for what had been a refining byproduct, gasoline.

October 1, 1920 – Gonzaullas becomes a Texas Ranger

Manuel T. Gonzaullas joined the Texas Rangers — and rowdy Texas boom towns would never be the same. He soon became known as “Lone Wolf” Gonzaullas.

“World’s Richest Acre Park, where once stood the world’s greatest concentration of oil wells.” A street scene in Kilgore, Texas, depicting steel derricks behind stores, is one of many by Russell Lee (1903-1986) preserved by the Library of Congress.

In East Texas, when the streets of downtown Kilgore sprouted oil derricks, the population grew from 700 to 10,000 in two weeks. With Depression-era petroleum discoveries multiplying, oil boom towns often attracted criminals. Riding a black stallion named Tony and sporting two pearl-handled .45 pistols, Gonzaullas soon earned a reputation for strictly enforcing the law.

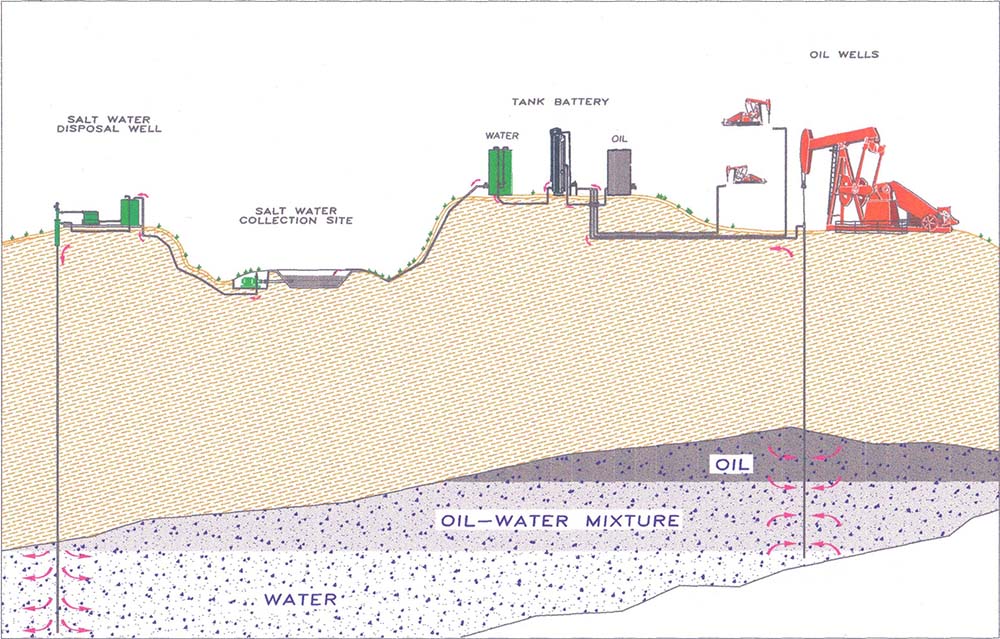

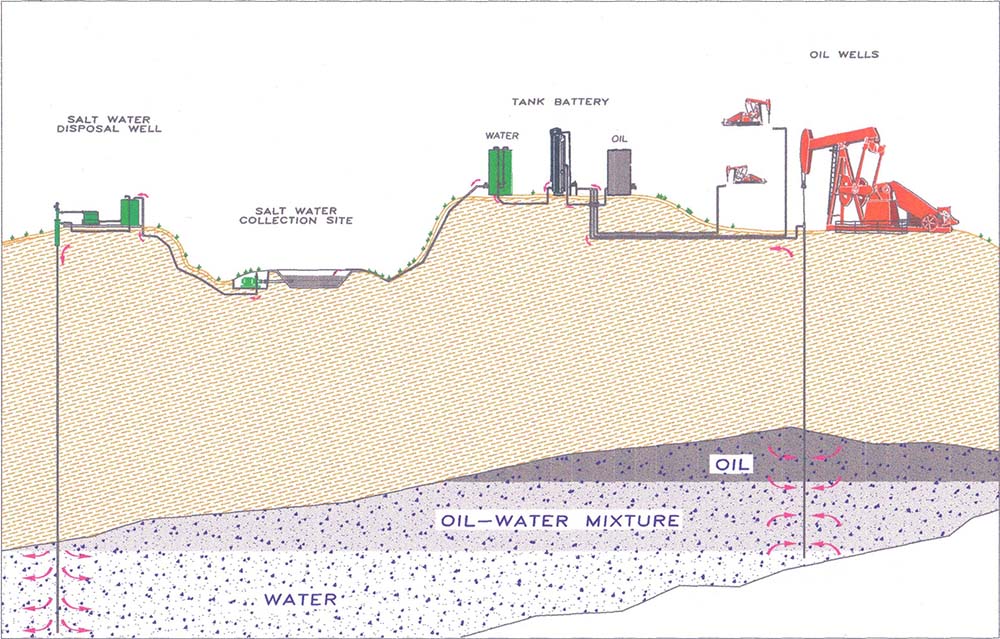

October 1, 1942 – Water Injection begins in East Texas

The East Texas Salt Water Disposal Company drilled the first saltwater injection well in the 12-year-old East Texas oilfield near the towns of Tyler, Longview, and Kilgore. As early as 1929, the Federal Bureau of Mines had determined injecting recovered saltwater into formations could increase reservoir pressures and oil production.

Saltwater injection wells improve oil production and keep marginal East Texas wells viable. Illustration courtesy East Texas Salt Water Disposal Company.

The Texas Railroad Commission established the saltwater disposal company as a public utility to operate in the oilfield. The company treated and reinjected about 1.5 billion barrels of saltwater in its first 13 years, prompting the commission to proclaim saltwater injection as the “greatest oil conservation project in history.”

October 2, 1919 – Future “Mr. Tulsa” incorporates Skelly Oil

Skelly Oil Company incorporated in Tulsa, Oklahoma, with founder William Grove Skelly as president. He had been born in 1878 in Erie, Pennsylvania, where his father hauled oilfield equipment in a horse-drawn wagon.

Born near Pennsylvania oilfields, William Skelly founded Skelly Oil Company in 1919 — and led an international petroleum exposition for 32 years, helping to make Tulsa the “Oil Capital of the World.”

Skelly’s success in the El Dorado oilfield east of Wichita, Kansas, helped him launch Skelly Oil and other ventures, including Midland Refining Company, which he founded in 1917. As Tulsa promoted itself as “Oil Capital of the World,” Skelly became known as “Mr. Tulsa.”

Skelly served as president of Tulsa’s famous International Petroleum Exposition for 32 years until his death in 1957.

October 3, 1930 – East Texas Oilfield discovered on Widow’s Farm

Ninety-five years ago, with a crowd of more than 4,000 expectant landowners, leaseholders, creditors, and others watching, the Daisy Bradford No. 3 wildcat well was successfully shot with nitroglycerin near Kilgore, Texas.

Spectators gathered on the widow Daisy Bradford’s farm near Kilgore, Texas, to watch the October 3, 1930, “shooting” of the discovery well of what proved to be the largest oilfield in the lower 48 states. Photo courtesy Jack Elder, The Glory Days.

“All of East Texas waited expectantly while Columbus ‘Dad’ Joiner inched his way toward oil,” explained historian Jack Elder in 1986. “Thousands crowded their way to the site of Daisy Bradford No. 3, hoping to be there when and if oil gushed from the well to wash away the misery of the Great Depression.”

Geologists were stunned when it became apparent the remote wildcat well on the widow Daisy Bradford’s farm — along with two other wells far to the north — were part of the same oil-producing formation (the Woodbine) that encompassed more than 140,000 acres. The “Black Giant” would produce billions of barrels of oil in coming decades.

Learn more in East Texas Oilfield Discovery.

October 3, 1980 – Museum opens in East Texas Oilfield

Fifty years after the discovery of the East Texas oilfield, the East Texas Oil Museum at Kilgore College opened as “a tribute to the independent oil producers and wildcatters, the men and women who dared to dream as they pursued the fruits of free enterprise.”

The East Texas Oil Museum since 1980 has hosted events and maintained exhibits preserving the “Black Giant” oilfield discovered during the Great Depression. Photos by Bruce Wells.

Established with funding from the Hunt Oil Company, the museum at Kilgore College recreated a 1930s boom town atmosphere. The museum, which is hosting special events on its 45th birthday, maintains a database that offers keyword search and advanced search options — along with a “random Images” button to browse photography from a wide assortment of online records.

October 4, 1866 – Oil Fever spreads to Allegheny River Valley

Just 15 miles east of Titusville, Pennsylvania, site of the first U.S. oil well, an oilfield discovery at Triumph Hill sparked another wild rush of speculators and new drilling. America’s petroleum industry was barely seven years old when wooden cable-tool derricks and engine houses replaced hemlock trees along the Allegheny River.

October 4, 1901 – Drake Memorial dedicated in Pennsylvania

More than 2,500 people, including his widow, Laura Dowd Drake, attended the unveiling of a monument to the “father of the petroleum industry,” Edwin L. Drake, who had died in relative obscurity in 1880. Standard Oil Company executive Henry Rogers commissioned the marble, semi-circle memorial in Titusville, Pennsylvania.

Unveiling of the Drake Monument in Titusville, Pennsylvania, on October 4,1901. Thousands attended the dedication in Woodlawn Cemetery. Photo by John Mather courtesy Drake Well Museum.

The monument, which includes a bronze statue by Charles Henry Niehaus, was dedicated in Woodlawn Cemetery. Learn more by visiting Titusville’s Drake Well Museum and Park.

October 5, 1915 – Science of Petroleum Geology reveals Oilfield

Using the new earth science of petroleum geology for finding oil led to the discovery of the giant Mid-Continent field in central Kansas. Drilled by Wichita Natural Gas Company, a subsidiary of Cities Service Company, the well revealed the 34-square-mile El Dorado oilfield.

The Stapleton No. 1 well in 1915 revealed the El Dorado, Kansas, oilfield, among the largest in the world. By 1919, Butler County had more than 1,800 producing oil wells. Photo by Bruce Wells.

“Pioneers named El Dorado, Kansas, in 1857 for the beauty of the site and the promise of future riches, but not until 58 years later was black rather than mythical yellow gold discovered when the Stapleton No. 1 oil well came in on October 5, 1915,” explained geologist Lawrence Skelton in 1997.

The Stapleton No. 1 well east of Wichita initially found oil at a depth of 600 feet before being deepened to 2,500 feet to produce 110 barrels of oil a day from the Wilcox sands. Natural gas discoveries one year earlier at nearby Augusta had prompted El Dorado civic leaders to seek their own geological study of Mid-Continent fields.

The Stapleton No. 1 well and the Kansas Oil Museum preserve a 1915 oil discovery. Photo by Bruce Wells.

The Kansas Oil Museum preserves the state’s petroleum heritage with historic oilfield equipment displayed on 10 acres east of the city. Museum exhibits describe how lessons from the El Dorado field helped launch petroleum geology as a profession while establishing El Dorado as a center for refining.

Learn more in the Kansas Oil Boom.

October 5, 1958 – Water Park opens in West Texas for One Day

A water park inside a Depression-era experimental concrete oil tank opened to the public in West Texas. The day’s festivities at Monahans attracted swimmers, boaters, anglers, and even water skiers to the massive, manmade lake — before leaks at the seams forced it to close the next day.

The Million Barrel Museum’s site was originally built to store Permian Basin oil. For scale, note the railroad car and caboose exhibit at upper right.

A local couple had attempted to find a good use for the 525-foot by 422-foot “million barrel reservoir” once covered by a redwood dome roof. The concrete tank had been completed in 1928 by Shell Oil due to a lack of pipelines for Permian Basin oil. Shell stopped using the tank because the company could not prevent oil from leaking at the seams.

Learn more in Million Barrel Museum.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Signal Hill, California – Images of America (2006); From Here to Obscurity: An Illustrated History of the Model T Ford, 1909 – 1927

(2006); From Here to Obscurity: An Illustrated History of the Model T Ford, 1909 – 1927 (1971); Artificial Lift-down Hole Pumping Systems

(1971); Artificial Lift-down Hole Pumping Systems (1984); An adventure called Skelly: A history of Skelly Oil Company through fifty years, 1919-1969 (1970); The Black Giant: A History of the East Texas Oil Field and Oil Industry Skullduggery & Trivia

(1984); An adventure called Skelly: A history of Skelly Oil Company through fifty years, 1919-1969 (1970); The Black Giant: A History of the East Texas Oil Field and Oil Industry Skullduggery & Trivia (2003); Early Texas Oil: A Photographic History, 1866-1936

(2003); Early Texas Oil: A Photographic History, 1866-1936 (2000); Western Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage

(2000); Western Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage (2008); The fire in the rock: A history of the oil and gas industry in Kansas, 1855-1976

(2008); The fire in the rock: A history of the oil and gas industry in Kansas, 1855-1976 (1976); Chronicles of an Oil Boom: Unlocking the Permian Basin

(1976); Chronicles of an Oil Boom: Unlocking the Permian Basin (2014). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2014). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.