As America fought the Korean War, the West Coast Pipeline Company received a government “certificate of necessity” in April 1952. Company President Lowell M. Glasco planned to build a 953-mile oil pipeline from Wink, Texas, to Norwalk, near Los Angeles.

To begin construction of his ambitous transportation infrastructure project, Glasco’s company needed a government partnership.

Pipeline projects were not a new business for Glasco – he had bid on lease contracts for the “Big Inch” and “Little Big Inch” pipelines after World War II. Those pipelines from Texas oilfields to East Coast refineries had been a joint industry and government effort.

Although the recent certificate of necessity was a tax amortization break essential to the success of the pipeline company’s plans, it did not guarantee construction. As the war in Korea dragged on, debate over building the pipeline began.

In September 1952, under headline of “New Oil Pipeline Across State Seen Boosting Income, “New Mexico’s Albuquerque Journal quoted bold predictions from the West Coast Pipeline Company president.

“This pipeline will open markets that will mean at least $187 million in new income for Texas and New Mexico,” Glasco said, adding that $87 million in debentures and bonds would soon be offered.

Glasco told the newspaper he had a permit to build the line from the Petroleum Administration for Defense. “He also has a National Production Authority allotment of 214,000 tons of steel,” the Journal reported. “The government has given his firm a 25 percent rapid tax write-off on the project.”

TIME magazine echoed the apparent progress toward start of the pipeline’s construction. “Said Dallas oilman Lowell M. Glasco last week, ‘This is the greatest thing that ever happened to the Texas oil business.’ Though somewhat exaggerated, Glasco’s news was indeed big.”

The TIME article added that West Coast Pipeline Company, “was ready to build the first crude-oil pipeline between the west Texas oilfields and the oil-hungry West Coast.” With an estimated cost of $87 million for construction, the proposed 953-mile pipeline’s diameter would match that of the “Big Inch” line (24 inches).

Lowell M. Glasco proposed an oil pipeline from Texas to California with the same 24-inch diameter as the “Big Inch” line (above) constructed from Texas to the East Coast during World War II. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

However, the end of the Korean War in July 1953 brought a new assessment of America’s economic priorities. Congress weighed in with committee hearings. Glasco testified before a House Armed Services Subcommittee that Texas oil was of better quality than heavier California oil. If California refineries used more West Texas oil, he said, “you would eliminate about 40 percent of this smog.”

Further, Glasco argued for the government-backed pipeline to relieve an oil shortage on the West Coast. But Army Brig. Gen W.W. White, representing the Defense Department, and H.A. Stewart, director of the Department of the Interior’s office of oil and gas, opposed government financing of such a pipeline.

As the controversy continued, the future of West Coast Pipeline Company hung in the balance.

On January 25, 1956, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Navy Admiral Arthur William Radford, asserted that without the war in Korea, there was no need for “peacetime construction of the pipeline with government backing,” adding that Glasco’s proposed pipeline “was not essential to national defense.

In case of another emergency, the admiral said U.S. petroleum needs could be met by oil imported from Canada and from naval oil reserves, including the one in Elk Hills, California. In another reply to congressional questions, he observed that “there was greater need for a pipeline to the East.”

It was the end of the line for West Coast Pipeline. After two-years of failure to pay required taxes to Delaware, on January 16, 1961, the state revoked Lowell M. Glasco’s pipeline company’s charter to do business.

First Pipeline Debate

The Civil War had barely ended when the Pennsylvanian Legislature in 1865 authorized construction of an oil pipeline not far from America’s first oil well. It was a first for the new U.S. petroleum industry. Recognizing the need to get crude oil to refineries for making kerosene, lawmakers allowed Samuel Van Syckel and his Oil Transportation Association to build a pipeline to a Venango County railroad station.

This marked the beginning of a technological boom for establishing market infrastructure (learn more about the petroleum industry’s earliest days in Oil Boom at Pithole Creek).

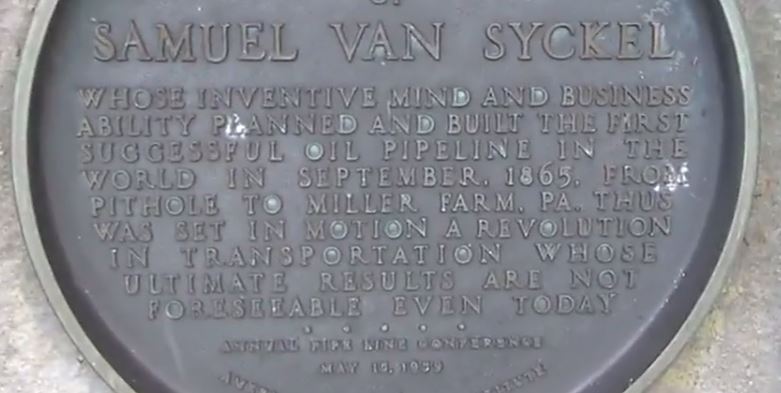

In 1959, the 100th borthday of the first U.S. oil well, the American Petroleum Institute dedicated a plaque to the builder of America’s first oil pipeline.

Van Syckel’s pipeline used two-inch-wide iron pipe to move oil from a well on the Frazier farm to the Oil Creek Railroad Station five miles away on the Miller farm. His new technology included 15-foot sections of pipe with welded joints.

To keep up the flow, pressure came from three 10-horsepower Reed and Cogswell steam pumps that could move 80 barrels of oil per hour. This was equivalent to 300 teamster wagons working for ten hours.

Those teamsters saw that their livelihood threatened by the new transportation technology. Angry debates began about pipeline economics, routes, and access. Acts of sabotage occurred. This was only the beginning of controversies over petroleum industry transportation, storage and infrastructure issues (see Trans-Alaska Pipeline History). They continue today.

___________________________________________________________________________________

The stories of exploration and production companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this AOGHS.ORG energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2018 Bruce A. Wells.