Acadia Parish oil seeps inspired 1901 Jennings oilfield discovery.

The first Louisiana oil well in 1901 revealed the giant Jennings field and launched the Pelican State’s petroleum industry. By 1911, offshore exploration included barges, floating pile drivers, and drilling platforms on Caddo Lake.

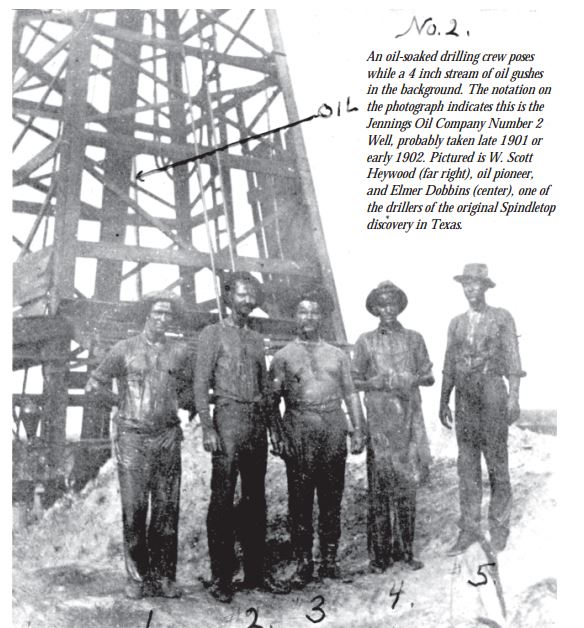

Nine months after the 1901 “Lucas Gusher” at Spindletop, Texas, oil erupted 90 miles to the east in Louisiana. W. Scott Heywood — already a successful wildcatter at Spindletop — drilled the discovery well of the Jennings oilfield. His September 21, 1901, gusher initially produced 7,000 barrels of oil a day.

Louisiana’s first commercial oil well, the Jules Clements No. 1, was completed on the Clements farm, about seven miles northeast of the small town of Jennings.

Mrs. Scott Heywood, “the widow of Louisiana’s oil discoverer, the late W. Scott Heywood,” unveiled a historical marker on September 23, 1951, as part of the Louisiana Golden Oil Jubilee. Times Picayune (New Orleans) image courtesy Calcasieu Parish Public Library.

Local investors earlier had formed the Jennings Oil Company and hired Scott, who recognized that natural gas seeps found nearby were nearly identical to the conditions observed at Spindletop. Scott would insist on drilling deeper than many investors thought wise.

The Jennings Oil Company No. 1 well, which discovered the first commercial oilfield in Louisiana on September 21, 1901. Photo courtesy Louisiana Geological Survey.

“At the age 29, W. Scott Haywood was already a seasoned, experienced and successful explorer,” noted Scott Smiley, a Louisiana Geological Survey (LGS) historian. “He had gone to Alaska in 1897 during the great Yukon gold rush, sinking a shaft and mining a profitable gold deposit.”

Haywood, who also had drilled several successful oil wells in California, was one of the first to reach Spindletop following news of the January 1901 oilfield discovery. Haywood eventually convinced the reluctant Clements to allow drilling in the farmer’s Acadia Parish rice field. The Clements farm was at the small, unincorporated community of Evangeline, northeast of Jennings.

However, after drilling to 1,000 feet without finding oil or natural gas, the Jennings Oil Company’s investors wanted to abandon the first attempt.

“After all, 1,000 feet had been deep enough to discover the tremendous oil gushers at Spindletop field,” explained Smiley in a 2001 history of the Jennings field. “Instead of drilling two wells to a depth of 1,000 feet each, Heywood persuaded the investors to change the contract to accept a single well drilled to a depth of 1,500 feet.”

More drilling pipe was brought in and the well deepened.

Deeper Drilling Pays Off

Heywood found signs of oil at a depth of 1,700 feet – after some discouraged investors had sold their stock when drilling reached 1,000 feet. By 1,500 feet, shares of the Jennings Oil Company still sold for as little as 25 cents each. Patient investors were rewarded when 7,000 barrels of oil per day suddenly erupted from the well.

“The well flowed sand and oil for seven hours and covered Clement’s rice field with a lake of oil and sand, ruining several acres of rice,” reported the Jennings Daily News.

W. Scott Heywood (5) and Elmer Dobbins (3) — “one of the drillers of the original Spindletop discovery in Texas.” Photo courtesy Louisiana Geological Survey.

Although the Jules Clements No. 1 well is on only a 1/32 of an acre lease, it marked the state’s first oil production and launched the Louisiana petroleum industry. It opened the prolific Jennings field, which Heywood developed by securing leases and building pipelines and storage tanks.

The Jennings oilfield reached its peak production of more than nine million barrels in 1906. Meanwhile, an October 1905 discovery in northern Louisiana further expanded the state’s young petroleum industry (visit the Louisiana Oil Museum in aptly named Oil City).

Haywood returned to Alaska in 1908 on a big-game hunting trip. He retraced much of his travels to the Klondike gold fields, notes Smiley. “After a brief retirement in California, he returned to Jennings and drilled several wells at Jennings and elsewhere in Louisiana,” Smiley reports, adding the he also found success at the Borger and Panhandle oilfields in Texas.

Rapid development of the Jennings oilfield in the early 1900s led to new conservation laws. A lack of spacing regulations forced “each leaseholder to drill their own well to prevent the draining of oil from the lease by an adjacent well.” Circa early 1900s photo courtesy Louisiana Geological Survey.

“Heywood returned to Jennings in 1927 and assisted Gov. Huey P. Long in passing legislation to provide schoolbooks for children,” concluded the geologist in Jennings Field – The Birthplace of Louisiana’s Oil Industry, September 2001.

Offshore Caddo Lake

Gulf Refining Company in 1911 drilled Ferry Lake No. 1 on Caddo Lake, Louisiana, using a fleet of tugboats, barges, and floating pile drivers. When the first well produced 450 barrels of oil per day, Gulf constructed platforms every 600 feet on each 10-acre lakebed (see Offshore Drilling History).

Although the Caddo Lake wells were often cited as the birthplace of America’s offshore drilling industry, oil patch historian in Mercer County, Ohio, discovered oil was produced from platforms on Grand Lake St. Marys as early as 1887.

In Pennsylvania, about 15 miles east of the first U.S. well at Titusville, dozens of wells produced oil on Tidioute Island and from rafts in the Alleghany River in the fall of 1860, according to the according to the Warren County Historical Society.

Challenging Louisiana Oil History

Extensive research by a retired professor at McNeese State University in Lake Charles challenged Louisiana petroleum history in 2011, according to the Southwest Daily News in Sulphur. The newspaper reported a September presentation at a Lake Charles library by Thomas Watson, PhD, who taught at McNeese State for 35 years, including a decade as the head of the history department.

“Dr. Thomas Watson has uncovered evidence that the first producing oil well in Louisiana was at the Sulphur Mines in 1886,” noted the newspaper, which was closed in 2024 after being acquired by MediaNews Group.

“This information could alter the history of oil production in Louisiana,” proclaimed the article, adding, “The interesting fact he has discovered in his research was announced formally at the Carnegie Library during a 10 a.m. presentation entitled ‘Oil and Sulphur Drilling’ on Sept. 6, 2011.”

The Weekly Echo was established in 1868, the same year Lake Charles was officially incorporated. The paper dropped the word “weekly” from its title in 1876, becoming the Lake Charles Echo, which ceased in 1898. Image courtesy Library of Congress (LOC).

Professor Thomas Watson’s 2011 Carnegie Library presentation on Louisiana petroleum history began with a story, according to the Southwest Daily News article “Retired Professor Challenges Louisiana Oil History.”

“There’s a story of D.S. Perkins, who saw a bear come out of the woods with oil on its paw. The group traced the tracks back to a spring (Choupique Bayou) with oil collecting on top. It came to be known as Oil Springs,” began Watson slowly. He explained that the oil spring produced a useable lubricant that was collected by people living around the area.

But the dream of oil was still alive. The Sulphur company decided to drill again in 1886.

During these years the Weekly Echo was the Lake Charles newspaper at the time, with editor John Wesley Bryan and publisher Dr. William H. Kirkman. Dr. Kirkman, along with the Perkins brothers from Sulphur, Eli and William, was following the activity at the mine and they, along with other investors, decided to drill again.

When the news broke out, the Weekly Echo announced a blow out! Gas came rushing back up to the surface. The well was capped, and the flow of oil was evaluated to [be] 25 barrels a day.

Watson said he considered it to be a heavy oil because it was perceived to be a first class lubricant. Good lube oil sold for more that thin oil (what Pennsylvania was selling). Louisiana crude would go for $5 a gallon as opposed to Pennsylvania oil at $1 a gallon.

The Weekly Echo documented the production and sale of oil from that Sulphur Mine source for three years. One report indicated maximum production hit 100 barrels a day. There were writings at the time that reported that the land around the Sulphur Mines was the richest 54 acres in the US at that time and this was true from 1895 until the 1920’s.

Therefore, 15 years earlier than the production of oil in Evangeline, they were marketing oil from Sulphur. Watson concluded his presentation citing Samuel Lockett documents.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Louisiana’s Oil Heritage, Images of America (2012); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946

(1982). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “First Louisiana Oil Well.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/first-louisiana-oil-well. Last Updated: September 15, 2025. Original Published Date: September 1, 2005.