Pennsylvania oilfield tragedy led to new safety and firefighting technologies — and a work of art.

The danger involved in America’s early petroleum industry was revealed when the first commercial well went up in flames just weeks after finding oil in the summer of 1859 — becoming the first oil well fire. More serious infernos would follow as the young industry’s early technologies struggled to keep up.

While the Pennsylvania oil region grew — and wooden derricks multiplied on hillsides — an 1861 deadly explosion and fire at Rouseville added urgency to the industry’s need for inventing safer ways for drilling wells.

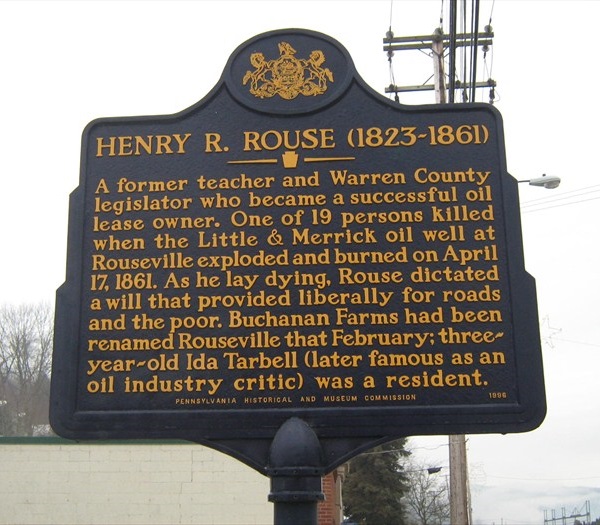

A marker was dedicated in 1996 on State Highway 8 near Rouseville by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Henry Rouse’s reputation made him a respected leader in the early oil industry.

On April 17, 1861, a highly pressurized well’s geyser of oil exploded in flames on the Buchanan Farm at Rouseville, killing the well’s owner and more than a dozen bystanders.

Sometimes called “Oil Well Fire Near Titusville” but more accurately, Rouseville, the early oilfield tragedy was overshadowed by the greater tragedy of the Civil War. Fort Sumter fell on April 13, 1861; Henry Rouse’s oil well exploded four days later.

The Little and Merrick well at Oil Creek, drilled by respected teacher and businessman Henry Rouse, unexpectedly had hit a pressurized oil and natural gas geologic formation at a depth of just 320 feet. Given the limited drilling technologies for controlling the pressure, the well’s production of 3,000 barrels of oil per day was out of control.

The Rouse Estate later reported, “A breathless worker ran up to him, telling him to ‘come quickly’ as they’d ‘hit a big one.’ According to the best accounts of the time, the ‘big one’ was the world’s first legitimate oil gusher. As oil spouted from the ground, Henry Rouse and the others stood by wondering how to control the phenomenon.”

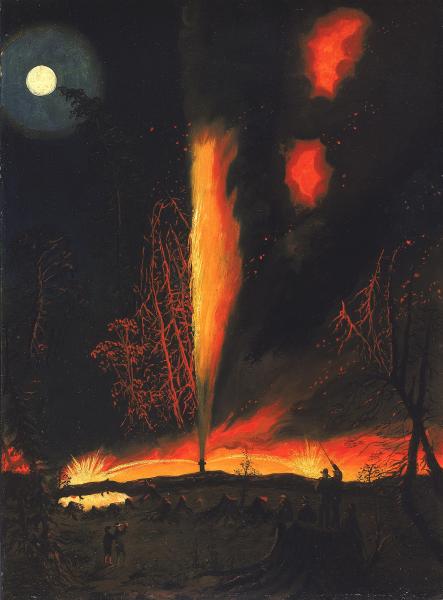

Detail from “Burning Oil Well at Night, near Rouseville, Pennsylvania,” a painting by James Hamilton of the 1861 oil well fire that killed Henry Rouse today is in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

The towering gusher also had attracted people from town; many had become covered with oil. Perhaps ignited by the steam engine’s boiler, the well suddenly erupted into flames that engulfed Rouse, killing him and 18 others and seriously burning many more.

Historian Michael H. Scruggs of Pennsylvania State University found a dramatic account from an eyewitness, who reported:

“One of the victims it would seem had been standing on these barrels near the well when the explosion occurred; for I first discovered him running over them away from the well. He had hardly reached the outer edge of the field of fire when coming to a vacant space in the tier of barrels from which two or three had been taken, he fell into the vacancy, and there uttering heart-rending shrieks, burned to death with scarcely a dozen feet of impassable heated air between him and his friends.”

Henry R. Rouse, 1823-1861.

Scruggs noted the 37-year-old Henry Rouse was dragged from the fire severely burned, and expecting the worst, dictated his Last Will and Testament, “to the men surrounding him as they fed him water spoonful by spoonful.”

Engraved on an 1865 marble monument (re-dedicated to Rouse’s memory during a family reunion in 1993) is this tribute:

Henry R. Rouse was the typical poor boy who grew rich through his own efforts and a little luck. He was in the oil business less than 19 months; he made his fortune from it and lost his life because of it. He died bravely, left his wealth wisely, and today is hardly remembered by posterity. — from the Rouse Estate.

The 1865 Atlas of the Oil Regions of Pennsylvania by Frederick W. Beers described this early petroleum industry tragedy in detail:

It was upon this farm (Buchanan) that the terrible calamity of April 1861, occurred, when several persons lost their lives by the burning of a well. The “BURNING WELL” as it has since been called, had been put down to the depth of three hundred and thirty feet, when a strong vein of gas and oil was struck, causing suspension of operations and ejecting a stream from the well as high as the top of the derrick.

“Atlas of the Oil Regions of Pennsylvania,” published by Frederick W. Beers in 1865.

Large numbers of persons were attracted to the scene, when the gas filling the atmosphere took fire, as is supposed, from a lighted cigar, and a terrible explosion ensued, which was heard for three or four miles. The well continued to burn for upwards of twenty hours destroying the tanks and machinery of several adjacent wells, and several hundred barrels of oil. The scene is represented as terrific beyond comparison.

The well spouted furiously for many hours, and the column of flame extended often two and three hundred feet in height, the valley being shut in, as it were, by a dense and impenetrable canopy of overhanging smoke. Fifteen persons were instantly killed by the explosion of the gas, and thirteen others scarred for life.

Among the persons killed was Mr. Henry R. Rouse, who had then recently become interested in that locality, and after whom Rouseville takes its name. The well continued to flow at the rate of about one thousand barrels per day for a week after the fire, when it suddenly ceased, and has since produced very little oil as a pumping well.

These fires have not been unfrequent, and it is a little remarkable that in every case where wells have been so burned they have never after produced save in very small quantities.

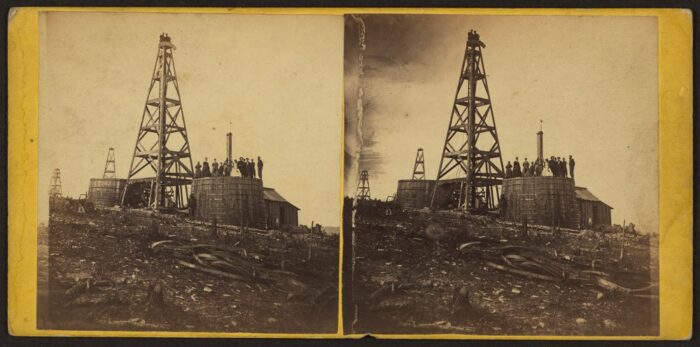

Late 1860s stereograph by William J. Portser showing men and women standing on a storage tank and two men at the top of an oil derrick in Pennsylvania, courtesy Library of Congress.

According to historian Scruggs, the knowledge gained from the 1861 disaster along with other early oilfield accidents brought better exploration and production technologies. The first “Christmas Tree” — an assembly of control valves – was invented by Al Hamills after the 1901 gusher at Spindletop Hill, Texas.

Although the deadly Rouseville well fire caused tragedy and devastation, “the knowledge gained from the well along with other accidents helped pave the way for new and safer ways to drill,” Scruggs wrote in his 2010 article.

“These inventions and precautions have become very important and helpful, especially considering many Pennsylvanians are back on the rigs again, this time drilling for the Marcellus Shale natural gas,” he concluded.

Learn more about another important invention, Harry Cameron’s 1922 blowout preventer in Ending Gushers – BOP.

Oil Well Fire at Night

The tragic Pennsylvania oil well fire was immortalized by Philadelphia artist James Hamilton, a mid-19th century painter whose landscape and maritime works are in collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the Tate Gallery in London, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) in Washington, D.C.

Acquired by the Smithsonian American Art Museum in 2017, artist James Hamilton’s “Burning Oil Well at Night, near Rouseville, Pennsylvania,” was on display in 2018. Photo by Bruce Wells.

In 2017, the Smithsonian museum acquired Hamilton’s “Burning Oil Well at Night, near Rouseville, Pennsylvania,” circa 1861 (oil on paperboard, 22 inches by 16 1⁄8 inches, currently not on view).

“Rouseville, Pennsylvania, lay within a few miles of Titusville and Pithole City, two of the most famous boom towns in Pennsylvania ’s oil fields,” noted the museum’s 2017 description of the painting.

“From 1859 until after the Civil War, new gushers brought investors, cardsharps, saloons, and speculators into these rural settlements. As quickly as they grew, however, the towns collapsed, often from the effects of fires like the one shown here,” noted the Smithsonian’s description.

Flames shooting from the wellhead are part of the circa 1861 “Burning Oil Well at Night, near Rouseville, Pennsylvania,” by James Hamilton.

“In the 1860s, American industrialist John D. Rockefeller (1839-1937) was in the thick of this oil boom, maneuvering to establish the Standard Oil Company,” the museum’s painting description added. “Rockefeller’s investments in railroads and refineries would make him one of America’s richest men, long after the wildcatters in the Pennsylvania fields had gone bust.”

Famed journalist and Rockefeller antagonist Ida Tarbell lived in Rouseville as a child.

Following the Civil War, with consumers increasingly demanding kerosene for lamps (and soon gasoline for autos), the search for oilfields moved westward. The young petroleum industry also developed safety and accident prevention methods alongside new oilfield firefighting technologies.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975); Atlas of the oil region of Pennsylvania (1984); Cherry Run Valley: Plumer, Pithole, and Oil City, Pennsylvania (2000); Warren County (2015). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information: Article Title: “Fatal Oil Well Fire of 1861.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/first-oil-well-fire. Last Updated: April 12, 2025. Original Published Date: April 29, 2013.