Going broke where a billion-barrel oilfield would be discovered in the 1870s.

When the Seneca Oil Company completed the first U.S. oil well along Oil Creek at Titusville, demand for crude oil from northwestern Pennsylvania boomed. The 1859 oil discovery launched a new industry, which soon constructed refineries to produce kerosene from oil instead of coal (coal oil) as a safe, inexpensive lamp fuel.

Engineer’s Petroleum Company, one of the early companies to explore east of Titusville, decided to search in the hills around the remote town of Bradford, near the New York border. Armed with detailed geologic studies, the company believed it had an edge for finding oil.

In 1836, famed scientist Samuel Prescott Hildreth published a geological study on the possibilities for salt production in southeastern Ohio. The respected pioneer physician and scientist had left Massachusetts in 1898 to settle in Marietta, along the banks of the Ohio River. His expertise helped salt well drillers, who were familiar with the “making hole” technologies the new petroleum industry needed.

Oil, Bane of Brine Drillers

Hildreth’s geological study, “Observations on the Bituminous Coal Deposit for the Valley of the Ohio, and the Accompanying Rock Strata,” identified anticlinal structural traps as features linked to drilling successful brine wells. Intended to help the search for that valuable food-preserving resource, his report’s revelation about the anticlines later would be important for many Ohio oil discoveries.

Importantly, Hildreth reported anticlinal rock formations were frequently associated with oil deposits. This was a warning for Ohio salt well drillers, who considered petroleum a problem, not a resource (see this article about a Kentucky salt driller’s oil well).

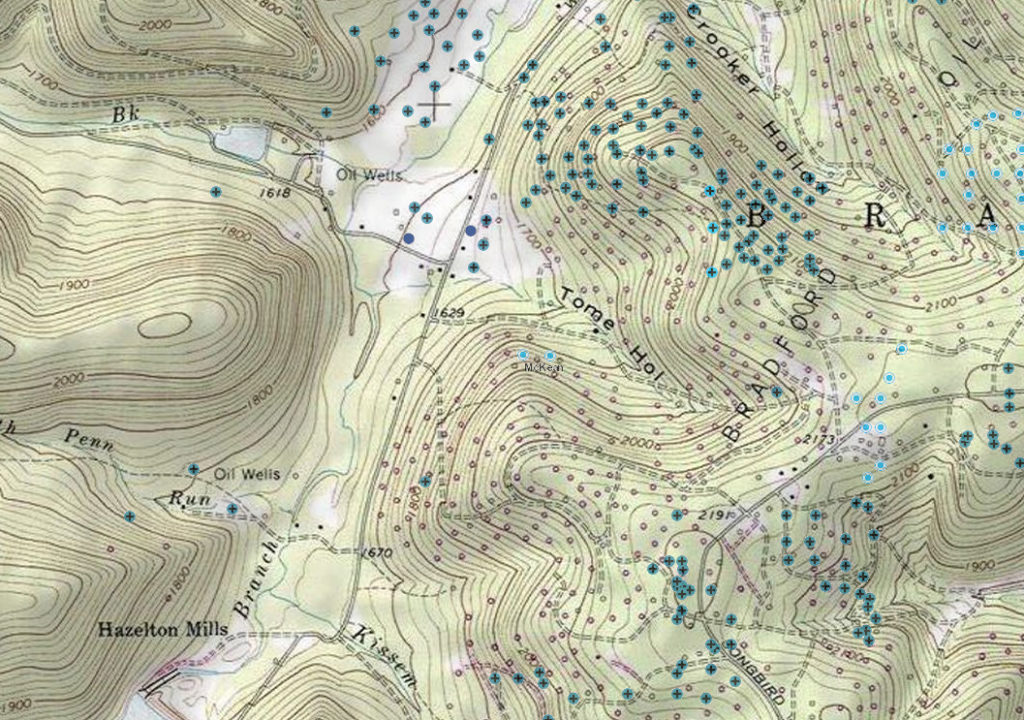

“This dale is evidently formed by upheavals which have taken place towards the end of the Devonian period,” explained the geologist seeking a site to drill for oil near Bradford, Pennsylvania. Prospective site’s topography image courtesy Pennsylvania Department of Natural Resources online mapping.

After Pennsylvania oil discoveries, exploration companies like Engineer’s Petroleum rushed to the state – where drilling equipment and lease prices soared. Hundreds of exploration companies organized in Titusville, Franklin, and Oil City as financiers, speculators, and drillers sought to invest in this new “black gold” industry.

In 1865, after a United States Oil Company oil discovery created the notorious boom town of Pithole, half-acre leases nearby sold for $3,000 each (about $45,000 in 2020 dollars). Fortunes were made or lost or squandered – most famously at the time by “Coal Oil Johnny”.

Under-capitalized speculators had to look to more distant, unproven territory, including Engineer’s Petroleum Company. About 65 miles northeast of Pithole (thorough today’s scenic Allegheny National Forest), a few exploratory wells had been drilled in McKean County, but few believed commercial quantities of oil could be found; leases could be had for at little as six cents an acre.

Falling into Anticlinal Traps

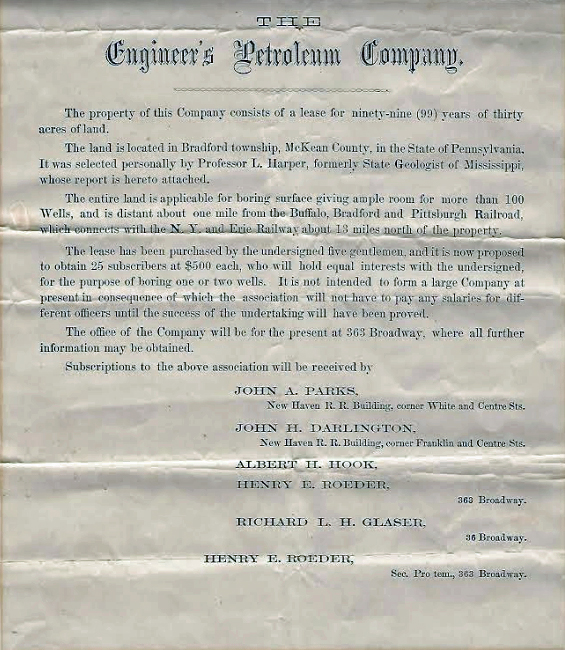

To attract investors, Engineer’s Petroleum Company cited geological reports about likely sites for successful oil wells, accompanied by this document offering lease units for sale. Document image courtesy Charles Laser.

To attract investors, Engineer’s Petroleum Company cited the best geological science of the day. Company executives also sought the well-regarded expertise of former Mississippi State Geologist Lewis Harper. The geology professor used Hildreth’s long-standing structural trap guidance to select a promising 30-acre site, “giving ample room for more than 100 oil wells.”

The exploration company selected a site southwest of Bradford Township, on a tributary of the West Bank of Tunungwant Creek. “This dale is evidently formed by upheavals which have taken place towards the end of the Devonian period, it is not simply a dale formed by the flowing of water run down from the hills,” Harper noted, further explaining:

“If now, before the upheaval of these hills from a horizontal position, petroleum had been formed or such animal or vegetable matter had been accumulated which gives origins to petroleum, this must have run down from the inclined planes and accumulated in the ground which has not been upheaved in the dale formed by the three hills.”

Unfortunately for Engineer’s Petroleum Company and its investors, Professor Harper and his colleagues’ theories were wrong about Pennsylvania’s anticline petroleum geology. Pennsylvania oilfields were mostly found in formations very different from those in Ohio. Historian and author Ray Sorenson has noted the misinterpretation (see Rocky Beginnings of Petroleum Geology) by pointing out, “theories of trapping did not work in the absence of anticlines.”

Early exploration company executives had learned geologists’ theories for finding oil were often no better than traditional creekology (and helpful oil seeps), dowsers, witching, or blind luck. James C. Donnell, later president of the Ohio Oil Company, began his career in Bradford’s early oilfields and declared, “The day The Ohio has to rely on geologists, I’ll get into another line of work.”

Experience and the science of petroleum geology advanced together over coming years, improving the odds of drilling and completing a successful well. Donnell had to revise his opinion of “college boys” when Ohio Oil Company’s first geologist, C.J. Hares, discovered 19 oil and natural gas fields. Donnell declared Hares to be, “the greatest geologist in the world.”

Engineer’s Petroleum Company, which never found oil at its “dale formed by the three hills,” would go bankrupt. But it would be proved right to have looked in the Bradford area. In 1871, another speculative venture, the Foster Oil Company, drilled a series of small producers east of the Main Branch of Tunungwant Creek, about five miles north of the old Engineer’s Petroleum site.

The Penn-Brad Museum and Historical Oil Well Park is located just south of Bradford on Route 219, near Custer City. Photo by Bruce Wells.

The Foster Oil Company wells revealed what ultimately led to America’s first billion-barrel oilfield. Production from the Bradford field peaked in 1881 when it produced more than 27 million barrels of oil – more than 75 percent of the world’s total output that year.

Today, in Custer City, a few miles south of Bradford, the Penn-Brad Oil Museum preserves “the philosophy, the spirit, and the accomplishments of a little-known oil country community — taking visitors back to the early oil boom times of ‘The First Billion Dollar Oil Field.'”

In addition to its historic oilfield – and being home to Zippo Manufacturing Company since the early 1930s – Bradford also boasts the world’s oldest continuously operating petroleum refinery; the American Refining Group, Inc. began processing 10 barrels of Pennsylvania crude oil a day in 1881.

_______________________________________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2020 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Engineers Petroleum Company.” Author: Aoghs.org Editors. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/stocks/engineers-petroleum-company. Last Updated: March 24, 2020. Original Published Date: March 24, 2020.