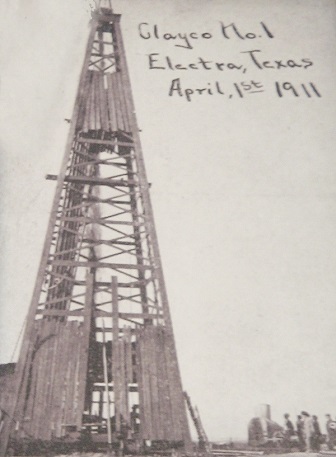

Some thought the 1911 oil discovery at Electra was an April Fool’s Day joke.

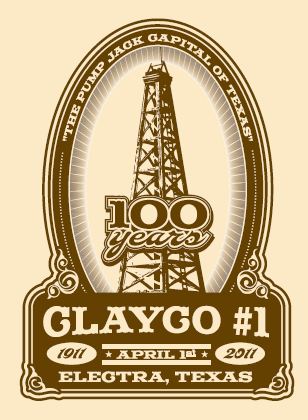

When a geyser of oil erupted from the Clayco No. 1 well near Electra on April 1, 1911, the giant oilfield discovery launched a boom that brought prosperity and more drilling to North Texas. Lawmakers would name Electra the “Pump Jack Capital of Texas.”

Just south of the Red River, Electra was a small, cotton-farming community barely four years old when petroleum exploration companies rushed to North Texas in 1911.

Excitement from “black gold” had not slowed by 1917, when another wildcat well erupted at Ranger in neighboring Eastland County. When a third massive oilfield discovery brought a drilling boom to nearby Burkburnett and Wichita Falls in 1918, even Hollywood noticed.

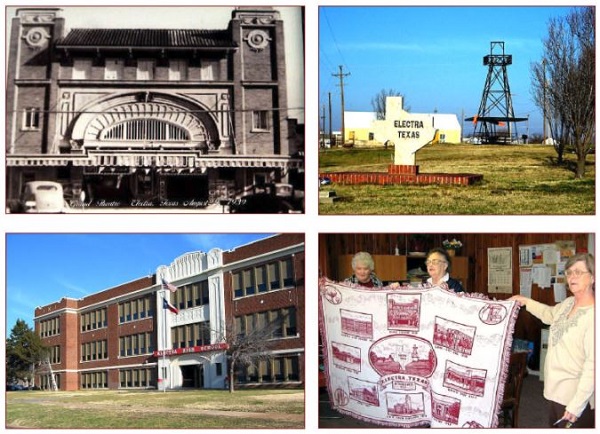

The 1911 oilfield discovery at Electra, Texas, helped finance construction of the community theater in 1920 and the high school in 1923. A Chamber of Commerce Afghan featured derricks in 2005, thanks to members Shirley Craighead, Georgia Eakin and Jeanette Miller. Color photos by Bruce Wells.

The series of oilfield discoveries brought hundreds of drillers and service companies to the sparsely populated region and launched new oil exploration companies. With the boom towns making national headlines, some speculators took advantage of unwary investors as far away as New York and California.

Mesquite Trees and Oilfields

The surge in North Texas oil production also would fuel America’s Model T Fords, help bring an Allied victory in World War I, convince Conrad Hilton to buy his first hotel, and inspire the Academy Award-winning movie “Boomtown.”

As early as 1913, new Mid-Continent oilfields like Electra were producing almost half of all the oil in the Lone Star State, where the first Texas oil well had been drilled in 1866. Refineries began to appear in Wichita Falls in 1915 when Wichita County alone reported 1,025 producing wells.

In October 1917, as World War I raged in Europe, a giant oilfield discovery was made at Ranger in Eastland County. The “Roaring Ranger” well gained international fame as the town whose oil wiped out critical shortages during the war, allowing the Allies to “float to victory on a wave of oil.”

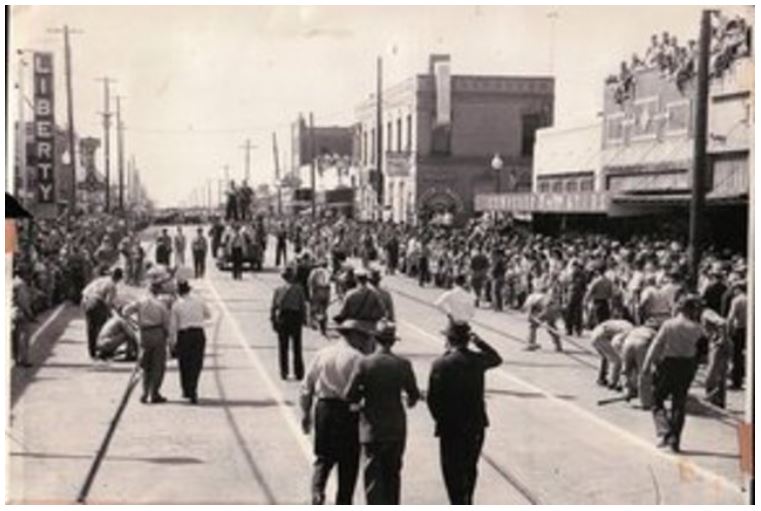

April 1, 2011, marked the centennial of the Clayco No. 1 well. Electra celebrated with a parade and ceremony at the well’s historic marker.

Within two years of the Ranger discovery, eight North Texas refineries were open or under construction and Ranger banks held $5 million in deposits.

Visiting Cisco after the Great War, a young Conrad Hilton saw long lines of roughnecks seeking a place to stay. Instead of the bank he had intended to buy, Hilton bought the two-story, red-brick hotel (see Oil Boom Brings First Hilton Hotel).

North of Cisco near the Oklahoma border, the Fowler No. 1 well at Burkburnett on July 28, 1918, produced 3,000 barrels of oil per day — triggering another boom that brought more companies to North Texas. An award-winning 1940 movie with Clark Gable, Claudette Colbert, Hedy Lamarr, and Spencer Tracy would be based on the wildcatters at the boom town of Burkburnett.

Today, the 2,800 residents of this oil patch community host an annual Pump Jack Festival celebrating their oilfield’s discovery well. Photo by Bruce Wells.

These discoveries further demonstrated the existence of a large petroleum-producing region in the central and southwestern United States — the Mid-Continent, which today includes hundreds of oilfields reaching from Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas into parts of Louisiana and Missouri.

Pump Jacks at Electra

The drilling boom at Electra, just south of the Red River border with Oklahoma, began in January 1911. Producers Oil Company revealed Electra’s oil potential when the Waggoner No. 5 well produced 50 barrels of oil a day from a depth of 1,825 feet. The discovery at a relatively shallow depth attracted the attention of a few independent operators.

Then came the oil gusher on April 1, 1911. At first, nobody believed what was happening when the Clayco Oil & Pipe Line Company’s Clayco No. 1 well erupted in a region previously known for its mesquite trees, bales of cotton, and cattle.

When news of the oil gusher spread, most people in town thought it was an April Fools joke — until they saw the black plume of oil in the sky. With a total depth of only 1,628 feet, the Electra oilfield discovery brought a rush of hundreds of exploration companies, investors — and many speculators (see Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?).

“That day secured Electra’s place in the history books as being one of the most significant oil discoveries in the nation,” proclaimed Bernadette Pruitt, a contributor to the Dallas Morning News. The Clayco gusher on cattleman William T. Waggoner’s lease settled into production of about 650 barrels per day.

Hundreds of other shallow-producing well completions quickly followed, leading to the oilfield’s peak production of more than eight million barrels in 1913.

A geyser of oil on cattleman William Waggoner’s lease settled into production of about 650 barrels per day from 1,628 feet. Hundreds of shallow-producing wells soon follow.

Founded in Wichita County in 1907, Electra was named after the spoiled daughter of cattle baron W.T. Waggoner (according to Texas Monthly, legend has it that Electra once blew $1 million in a single day at Neiman Marcus).

The rancher, whose property surrounded most of the town, had complained about finding oil when drilling water wells for his massive herds of cattle.

After the oil discovery, Electra’s population grew from 1,000 residents to more than 5,000 within months. But Pruitt explained that the chaos often associated with oil booms was kept to a minimum, because much of the surrounding land had been leased.

“Downtown Electra was packed in 1951 when the city celebrated the 40th anniversary of the Clayco No. 1 well discovery.” Photo and caption from downtown anniversary parade courtesy Electra Times Record News.

Pump Jack Festival

Electra celebrated the centennial of its oil discovery with a festival in 2011. The Texas legislature proclaimed the community “Pump Jack Capital of Texas” — with 5,000 of the counter-balanced pumping units in a 10-mile radius (see All Pumped Up — Oilfield Technology).

“Like mesquite trees, the jacks are such landscape fixtures that most Electrans pay little attention to them,” said Pruitt. “But tourists do…They’d move their hands up and down and say, ‘What’s that out there?'”

“Oil wealth would build infrastructure, schools, churches, and civic pride in Electra for generations,” explained Mayor Curtis Warner in 2013, adding that the motto of the chamber of commerce and agriculture’s logo was “Cattle, Crude, and Combines.”

In 1994, Electra’s Grand Theatre became a community fundraising and rehabilitation project; a new floor and handicap-accessible entry were completed in 2009. Photo courtesy Electra Star News.

Festival highlights include petroleum history photographs exhibited inside Electra’s Grand Theatre; a walking tour of antique oil equipment, including the Clayco well’s boiler; a special Chuck Wagon Gang Lunch and Chili Cook-Off; and educational events for young people.

“Electra’s downtown historic Grand Theatre on Waggoner Street has been a community landmark since 1919. Designed by the Ft. Worth architectural firm of Meador and Wolf, it cost $135,000. The Grand once hosted Vaudeville traveling troupes, and both silent and talking picture shows.

A historic marker for the Clayco No. 1 well just outside Electra includes the names of the drilling crew, the well’s depth (1,628) and, “Here flowed oil April 1, 1911, opening one of world’s largest oilfields.” Photo courtesy Wichita County Historical Commission.

Although work remains “to save the Grand,” the theatre was recognized by the Texas Historical Commission with Registered Texas Historical Landmark status in 2006 and today hosts community theatre and events.

Buffalo-Texas Oil Company

Typical of widely publicized oil booms (see Pithole Creek, Pennsylvania), many who rushed to Electra seeking quick profits, just as quickly departed. Intense competition throughout the Mid-Continent discoveries made drilling prospects harder to find. Most companies arrived too late. Unable to find equipment or afford lease prices, some went bankrupt without drilling a single well.

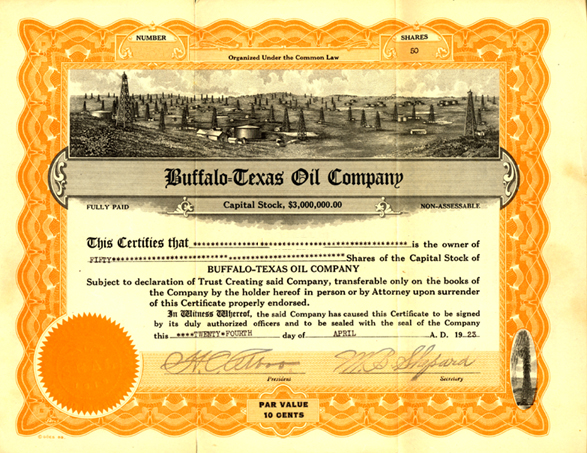

The successive drilling booms in Electra, Ranger and Burkburnett brought newly formed companies to North Texas — but as historian Pruitt noted, much of the land already had been leased. Typical of those seeking quick profits was the Buffalo-Texas Oil Company, which began issuing stock certificates to investors in 1919. Using stock sales to fund drilling was common, but sufficient capital often could not be raised to drill a well — especially as equipment and service prices soared.

Buffalo-Texas Oil Company’s stock certificate includes a vignette of derricks. The very same scene can be found on certificates from other quickly organized oil exploration companies.

Some of Buffalo-Texas Oil’s certificates cite capital of $3 million in 1923 — but the stock issue may have been an unsuccessful effort to raise sufficient venture capital to purchase leases and proceed with exploration.

Although the company’s establishment corresponds with a post-WW I surge in demand for petroleum, Buffalo-Texas Oil folded in 1928 with a final offer of a half cent per share. The company never drilled a well.

Like other start-up exploration companies in a rush to print stock certificates to impress potential investors, Buffalo-Texas Oil, the Double Standard Oil & Gas Company, and many others used the same oilfield vignette. The certificates featured scenic hills crowded with wooden derricks and oil tanks — the same scene found on certificates of many companies formed (and failed) at about the same time.

Learn more about the companies that competed for investors during oilfield booms in the Centralized Oil & Gas; the Double Standard Oil & Gas; the Evangeline Oil Company; the Texas Production Company; and the Tulsa Producing and Refining Company.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Early Texas Oil: A Photographic History, 1866-1936 (2000); Wildcatters: Texas Independent Oilmen

(1984); The Big Rich: The Rise and Fall of the Greatest Texas Oil Fortunes

(2009); Texas Oil and Gas (2013). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Pump Jack Capital of Texas.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/pump-jack-capital-of-texas. Last Updated: April 10, 2025. Original Published Date: March 11, 2005.