Abundant 19th-century natural gas supplies attracted manufacturers away from coal.

Natural gas discoveries of the 1880s revealed the giant Trenton Field in Indiana, which extended into Ohio. New pipelines and abundant gas supplies would attract manufacturing industries to the Midwest — where small towns competed with cities to attract new industries. It was an Indiana natural gas boom too good to last.

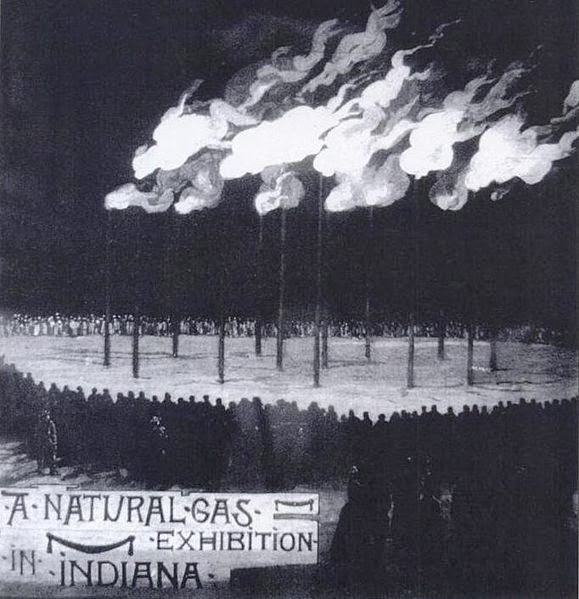

First used to promote abundant natural gas supplies, Indiana lawmakers banned flambeaux displays in 1891 — among the first states to legislate conservation. Photo of Findlay during its 1888 Gas Jubilee courtesy Hancock Historical Museum.

Discoveries of natural gas near the Indiana towns of Eaton and Portland quickly ignited a drilling boom. Petroleum exploration and production would change the state’s economy and provide a new energy source for manufacturers.

Distilled Coal Gas

By 1859, the same year that Edwin L. Drake drilled the country’s first U.S. oil well in Titusville, Pennsylvania, almost 300 “coal gas” companies operated in the 33 United States.

Coal gas was produced in a distillation process that extracted it from wood or coal. After further purification, the gas was distributed via low-pressure street mains to consumers. America’s first public street lamp used this manufactured gas to illuminate Market Street in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1817. This coal gas would illuminate the homes of almost five million customers.

Although natural gas was known to burn cleaner, hotter, and more efficiently than coal gas, pre-Civil War technology made handling it too dangerous for commercial applications. When drilling for oil, natural gas was often found — a colorless, odorless, highly flammable and unwelcome hazard.

Drillers sought oil to send to refiners for distilling into kerosene, a safe and affordable lamp fuel. Demand for kerosene brought wooden derricks to the Allegheny River Valley (see Derricks of Triumph Hill), and the coal gas business continued to prosper, but natural gas remained an impediment.

Although wasteful, natural gas demonstrations attracted crowds — and manufacturers like Kokomo Opalescent Glass Works, which continues to operate today. Photo from Leslie’s Illustrated Magazine, January 18, 1889.

After the Civil War, the great industrial cities of the North continued to expand and new manufacturing centers developed where natural resources and transportation met. Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and Toledo built coal-fired foundries and factories where iron, steel, and glass were produced in huge quantities for an expanding nation.

Indiana Gas Boom

Throughout the Midwest, railroads brought new industries into what were once almost exclusively agrarian economies. Coal and increasingly oil were in great demand as natural gas began entering the energy mix.

Indiana’s first official natural gas well is credited to G. Bates, who found gas while drilling for oil at a depth of 500 feet in 1867. Two decades later, nearby gas wells piped gas into Francesville, Pulaski County, for about four years. With manufacturers dependent on coal-fired boilers, the search for coveted coal seams continued.

In 1885, Andrew Carnegie said that the natural gas he used for steelmaking had replaced 10,000 tons of coal a day.

In 1876, W.W. Worthington, superintendent of the Ft. Wayne & Southern Railroad, and partner George W. Carter, an experienced quarry owner, explored for coal by boring a two-inch-wide test core 50 feet from railroad tracks in Eaton, Indiana. At a depth of 606 feet, they ran into “an ill-smelling gas” that readily ignited into a two-foot high flame.

Worthington and Carter had drilled into a natural gas deposit suffused with malodorous sulfur. Disappointed with not finding coal, they capped their pipe and moved on. Carter would return to the site about 10 years later.

Meanwhile, natural gas as an energy source began clearing skies in Pennsylvania. The state’s numerous iron and steel blast furnaces offered the first large-scale industrial use of natural gas, especially in “Smoky City,” Pittsburgh. Industrialist Andrew Carnegie proclaimed in 1885 ths natural gas he used for making steel had replaced 10,000 tons of coal a day.

The use of natural gas in steel mills also revealed that it could provide a competitive advantage to manufacturers with the good fortune to be located near a source (See Natural Gas is King in Pittsburgh). Energy-dependent industries looked for promising locations. Discoveries of gas fields brought attention, and producing towns and cities vigorously competing to attract new businesses.

“Great Karg Well”

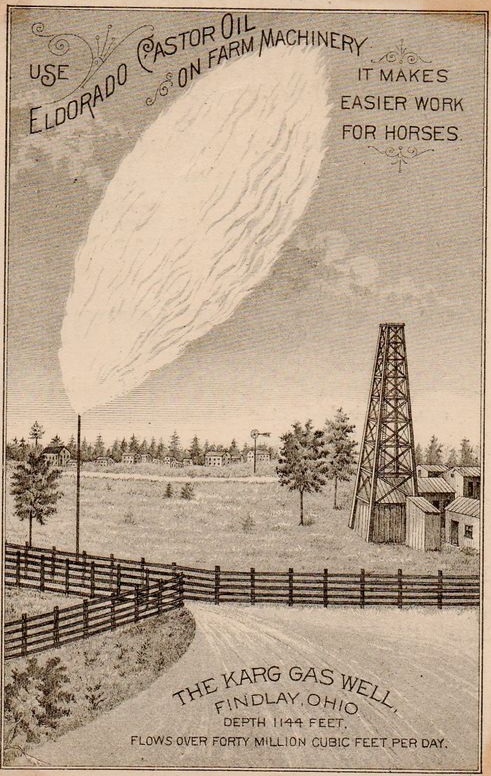

Near Findlay, Ohio, the spectacular “Great Karg Well” erupted natural gas on January 20, 1886, with an initial flow of 12 million cubic feet per day. With the limited technology of the day, the well’s pressure could not be brought under control and ignited, producing a towering plume of fire that burned for four months (learn more about controlling wells in Ending Oil Gushers – BOP).

One hundred miles southwest of Findlay, in Portland, Indiana, foundry owner Henry Sees followed the dramatic news from Findlay. He became convinced there was natural gas to be found in Portland as well. His enthusiasm eventually persuaded local investors; in 1886 they formed The Eureka Gas & Oil Company to drill in Portland.

An 1886 natural gas well’s pressure could not be controlled by technology of the day; it became a tourist attraction. Image courtesy Hancock Historical Museum.

On March 28, 1886, at a depth of 700 feet, Eureka Gas & Oil discovered a giant Indiana natural gas field.

The Portland Sun newspaper announced “NATURAL GAS!” in Indiana, reporting, “a strong blaze shot up from six to eight feet and was allowed to burn for some time for the edification of the multitude who jostled about, fell over each other and crowded the derrick house.”

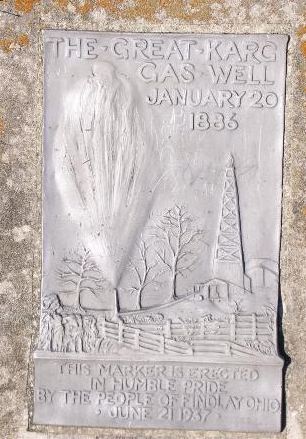

Many companies promoted Ohio’s natural gas supplies, which attracted glass companies from around the world, until the gas ran out. Image courtesy Historical Marker Database.

Eureka Gas & Oil Co. raised additional funds to drill another well a half-mile away. Drilling continued until a sudden and continuous rush of natural gas scrambled the crew to extinguish any nearby source of ignition. When the second well’s gas was piped out from the derrick and safely lighted, it flamed 15 feet into the air.

The well’s output was estimated to be 100,000 cubic feet per day. Investors quickly formed the Portland Natural Gas & Oil Company to continue drilling natural gas wells and pursue delivery to the town.

Like Indiana, Ohio greatly benefited from natural gas discoveries — as indicated by this 1937 marker “erected in humble pride by the people of Findlay, Ohio.” Photo courtesy Hancock Historical Museum.

By April 1887, five miles of main pipe was supplying natural gas to offices, residences and 50 large torches or “flambeaux” for street lighting. That same month, local businessmen organized the Manufacturers’ Gas & Oil Company for the specific purpose of providing free gas to manufacturers as an incentive to locate their factories in Portland.

Trenton Field Discovery

George W. Carter was among the thousands who traveled to Ohio in 1886 to see the Great Karg Well. Carter was the quarry owner who had searched for coal unsuccessfully in Eaton, Indiana, 10 years earlier.

At the well, Carter instantly recognized a disagreeable but familiar odor and declared, “That stuff smells like our coal mine!” Carter returned to Eaton, determined to drill at the railroad site he and W.W. Worthington had once deemed worthless.

With the Ohio gas discoveries exciting speculation, Carter and Worthington convinced Ft. Wayne and Eaton investors of the long-abandoned borehole’s potential. They established Eaton Mining & Gas Co. in late February 1886. After drilling beyond the earlier 606-foot depth, they hit a strong flow of natural gas at 922 feet on the night of September 15, 1886.

With a two-inch pipe extended 18 feet above the derrick, the gas produced a flame reportedly visible in Muncie, 10 miles away. It heralded what proved to be the 5,120-square-mile Trenton natural gas field.

The discoveries of natural gas in Eaton and Portland ignited an Indiana exploration and production boom that changed the state’s economy. As the scramble began, the Indianapolis News reported, “It’s a poor town that can’t muster enough money for a gas well…”

The Trenton field, as it would become known, spread over 17 east central Indiana counties. It was the largest natural gas field known in the world. Within three years, over 200 companies in Indiana were exploring, drilling, distributing, and selling natural gas from more than 380 producing wells.

Gas was so plentiful that customers were charged by the month or year rather than for a metered amount of gas.

The rapid growth and industrialization that Findlay, Portland and Eaton experienced was repeated again and again in Indiana’s “Gas Belt.” Cities like Muncie, Kokomo, Anderson, and Marion competed to attract new industries with offers of free natural gas, land, railway sidings, and tax credits.

On October 6, 1886, in Kokomo, a 900-foot-deep natural gas well in a corn field created the Indiana Natural Gas Company and led to establishment of the Opalescent Glass Works two years later. In continuous operation ever since, Kokomo Opalescent Glass began selling thousands of pounds of stained glass to Tiffany Glass Company and electric insulators to Edison General Electric.

By 1890, lured by generous incentives, 162 “Gas Belt” factories were built, creating over 10,000 jobs. Among the new industries were tinplate mills in Anderson, Gas City, and Elwood as well as 21 new glass factories. Ball Brothers Glass Manufacturing relocated to Muncie from Buffalo, N.Y.

As the gas boom continued, communities took great pride in what they thought to be their unlimited supply of natural gas. Estimated production in 1890 was almost 40 billion cubic feet. It became fashionable to erect arches of perforated iron pipe and let them burn brightly day and night for month after month.

Industries looked for promising locations in Indiana and Ohio as towns competed to attract them. Photo of downtown Findlay during Gas Jubilee of 1888 courtesy Hancock Historical Museum.

There were calls for conservation, but they went largely unheeded.

Boom to Bust

In 1893 the State Inspector of Natural Gas wrote, “The waste has been criminal and the day of repentance is fast approaching, and can only be delayed by practicing the most rigid economy and unrelaxed efforts in the husbandry of this valuable resource of our State.” Signs of the approaching crisis became increasingly evident — dropping pressure at wellheads.

By 1902, low pressure in the majority of the state’s gas wells was resulting in salt-water intrusion. Increasing numbers of wells stopped producing natural gas. Many of the manufacturers who had come to Indiana for the ready supply of cheap energy either went out of business or had to move when their natural gas sources failed.

Glass manufacturing companies were particularly hard hit.

In 1907, Indiana Glass Company consolidated several failing glass companies in Dunkirk — and imported Kentucky and West Virginia coal to create its own gas.

Thousands of jobs were lost to plant closings in other manufacturing industries. National Tin Plate, Ames Shovel, Indiana Box, American Wire & Nail, Viehl Carriage, and Anderson Bottling all succumbed to the depletion of natural gas. Indiana’s gas boom ended almost as quickly as it had begun. By 1913, Indiana was importing natural gas from West Virginia to meet demand.

The gas boom was over, and Indiana became a consumer rather than producer of natural gas in the 1920s. The consumption and waste so characteristic of Indiana’s gas boom provided other states an important lesson, the necessity to manage the use of natural resources.

Positive Legacy

The economic boom’s positive impact remains in many Indiana communities, according to Discover Indiana, which note the city of Kokomo more than doubled in population.

“The history of Indiana’s gas boom is one of entrepreneurs, inventions, and squandered natural wealth,” explains a Discover Indiana article. “It is the story of the turning point that made Howard County, Kokomo, and many other communities in east-central Indiana what they are today.”

The state’s public history project offers other insights and links to resources, including the Howard County Historical Society in Kokomo and the Hays Museum, once the mansion of Elmer Hays, designer of “a device to remove moisture from natural gas, which had been clogging the new pipelines with ice.”

In Ohio, the Hancock Historical Museum in Findlay preserves natural gas history — and is less than two miles from the site of the famous Karg well, which a historic marker on June 21, 1937, “erected in humble pride by the people of Findlay, Ohio.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); Natural Gas: Fuel for the 21st Century (2015); Natural Gas for the Hoosier State

(1995). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information: Article Title – “Indiana Natural Gas Boom.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/indiana-natural-gas-boom. Last Updated: March 22, 2025. Original Published Date: February 1, 2010.