Irene Hathaway sold encyclopedias door to door before taking a chance in Texas with the Big Indian Oil & Development Company and becoming a woman wildcatter.

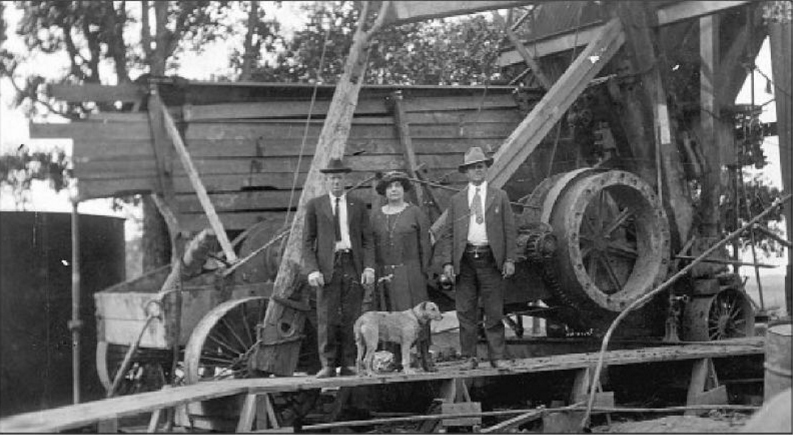

Irene Hathaway stands with two unidentified men at the first oil well in Cooke County, Texas, in 1924. Photo courtesy F.W. Blagg, Morton Museum of Cooke County.

Drilling for petroleum in unexplored regions – wildcatting – began with the first American oil well in 1859.

Over the years and despite advances in drilling technologies and the science of geology, nine out of 10 wildcat wells would be dry holes.

Despite the risk, thousands of companies and investors took the expensive gamble and drilled exploratory wells. A few of these wildcatters became legendary, but most were soon forgotten. They almost always were men. Almost always.

Irene Hathaway decided to become a Texas wildcatter while visiting a small town in 1918. She was a single woman in her 50s from Kansas City, Missouri, who went to Texas to peddle encyclopedias. She came across the tiny hamlet of Callisburg, populated by about 100 hardy farming souls. After hearing rumors of “huge untapped reservoirs of oil,” she began searching for anyone who would gamble on a lease.

“One of my favorite stories of Cooke County is that of wildcatter Ms. Irene Hathaway,” notes Jayleane Mays Smith, director of the Morton Museum in Gainesville, who researched the oil-patch business woman. She found that Hathaway had begun leasing land in 1919 near Callisburg in northeastern Cooke County.

In 1922 the encyclopedia saleswoman convinced representatives of the Big Indian Oil & Development Company to drill two miles east of Callisburg. She also convinced farmer Bud W. Davis to lease his land for drilling, “which at that time was sheer speculation,” Mays Smith notes in a 2014 article.

Drilling started at 6:30 p.m. on Tuesday, August 15, 1922, reported the Gainesville Daily Register. “The machinery and the bit began boring into the earth. The vibration could be felt over a wide area.”

Hathaway took up residence in Gainsville, just a few miles from the well. She visited often as drilling continued month after month – for two years.

“The company was ready to abandon the location, but Irene was convinced oil was there,” Mays Smith reports. “She strongly encouraged them to continue drilling just a little while longer, even making them an offer to pay the workers with money from her own pocket.”

On November 9, 1924, Big Indian Oil & Development brought in an oil gusher from 3,535 feet deep. Mays Smith says the Davis family reportedly was seated at the kitchen table, “leisurely enjoying a Sunday dinner when their 16-year-old son, Ray, looked out the window and shouted, ‘The well’s blowin’! Let’s run down and see it!'”

Mays Smith further reports that Bud Davis calmly said, “‘Eat your dinner, son. They’ll take care of that well ‘til we get through eatin. ‘”

News of the wildcat discovery spread quickly. Within days more 5,000 spectators had come to watch the company tame its No. 1 Davis well. Lease prices skyrocketed for miles around as oil fever spread.

“I believe this story lives on because people were fascinated not only by the drilling process, but also by Ms. Hathaway and her vision,” concludes Mays Smith.

Irene Hathaway was 80 when she died in 1949 in Gainesville – without great wealth, but with a story that survives in the Bob Bullock Museum Texas Story Project, Ms. Irene Hathaway, Wildcatter. In 2012 Cooke County oil revenues reached more than $575 million.

Today, a Texas Historical Commission marker commemorates Cooke County’s first oil-producing well, noting a “carnival atmosphere prevailed while sightseers and reporters flocked to the lease. One enterprising man charged admission until questioned by a worker.”

Big Indian Oil & Development Company

A 1976 Texas Historical Commission marker documented Cooke Country’s first oil well of 1924.

Big Indian Oil & Development had been formed in Kansas City, Kansas, on April 8, 1920, with C.A. Doudrick as president and Harry Doudrick as secretary-treasurer. Stock sales were key to financing the company and promising oil prospects like Hathaway’s were key to its success – and survival.

Although the Cooke County 1924 well settled into producing just 10 barrels of oil a day, production would last until 1970. Interviewed in 1979, land owner Bud Davis remembered the feverish investing caused the county’s first oil well:

“It caused a lot of money to be spent there because people come in there and bought acreage…some of them eight to ten miles away,” he said. “They didn’t know where that oil went to and they was just so anxious to get a little interest in some oil there they just buy whatever they could buy.”

Only a month after completing the No. 1 Davis well, Big Indian Oil & Development sold it and other suddenly valuable holdings near Callisburg. The company wanted to finance further drilling using more advanced rotary technology.

This January 1935 Big Indian Oil & Development Company newsletter to investors was among the last.

By June 16, 1926, a Sherman, Texas, newspaper noted Big Indian Oil & Development had signed two year extensions on several leases with Vacuum Oil Company, a subsidiary of Standard Oil. It also was announced the company (now with offices in Gainsville) had received an offer to expand exploration efforts into Mexico.

However, the company struggled during the Great Depression and with production from the giant East Texas oilfield lowering oil prices. One of the last company newsletters advised shareholders in January 1935: “The industry thus approaches the new year with courage and with hope. It has experienced a year marred to some extent by hot oil and price wars…”

Big Indian Oil had completed its Cooke County well when Texas oil sold for $1.52 a barrel. The East Texas oilfield soon produced more than 216 million barrels of oil, driving prices even lower. When prices reached 94 cents per barrel in 1935, Big Indian Oil & Development did not survive.

Legendary Oilmen & Women

Oilmen like Thomas Slick became famous when they beat the odds and struck oil. Once known as Dry Hole Slick, in 1922 he discovered the giant Cushing oilfield and became known as Oklahoma’s King of the Wildcatters. By 1929 his net worth was between $35 million and $100 million.

But Slick was the exception in the high-risk U.S. oil patch, where far more exploration ventures struggled by or went bankrupt. With investors and speculators paying the bills in this male dominated industry, it took determined women like Irene Hathaway to succeed. Earlier there was Mrs. Byron Alford.

During the industry’s earliest days in Pennsylvania, Alford was the “Only Woman in the World who Owns and Operates a Dynamite Factory,” proclaimed a Bradford newspaper in 1899. As owner of Mrs. Alford’s Nitro Factory, she was an astute businesswoman in the midst of America’s first billion dollar oilfield, which in 1881 supplied 77 percent of the world’s oil.

Another example is a former piano teacher who gained control of the Los Angeles oilfield – and for decades was known as the California Oil Queen. Emma Summers’ first Los Angeles well was drilled about a mile west of today’s Dodger Stadium.

“I saw a chance in the oil business and sunk a well, and that carried me on and on until I couldn’t stop,” she later explained. Her wells produced 50,000 barrels a month.

At first she sold her oil through local brokers, but eventually took on that challenge in addition to managing her supplies, 40 horses, 10 wagons and a blacksmith shop. “There are men in Los Angeles who do not like Emma A. Summers,” noted a 1911 issue of Sunset magazine as her petroleum interests grew.

Summers, who died in a Glendale nursing home in 1941 at age 83, had a “genius for affairs.” Her control of Los Angeles oilfields earned the former piano teacher her title.

___________________________________________________________________________________

The stories of other exploration attempts to join petroleum exploration booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research at Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

Please support the American Oil & Gas Historical Society and this website with a donation. © AOGHS.