A popular 1837 book by Washington Irving helped reveal natural resources of the Far West.

Tales of a Wyoming “tar spring” convinced the experienced Pennsylvania oilfield explorer Mike Murphy to drill a shallow well in 1883. He sold his oil to Union Pacific to lubricate train axles. Others would follow in the search for Wyoming oilfields.

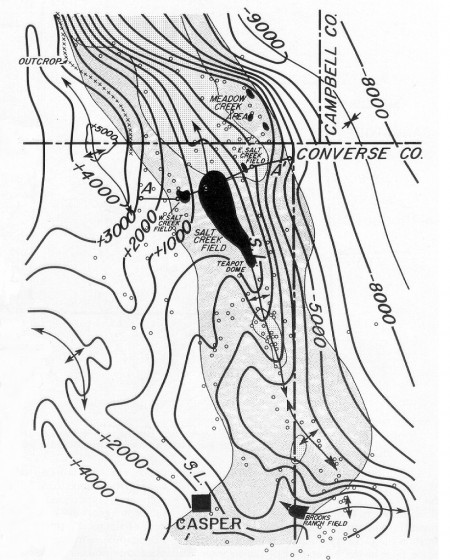

Civil War veteran Philip Shannon explored for oil at Salt Creek outside of Casper in 1890. His well revealed what proved to be a 22,000-acre oilfield. An oil gusher drilled by a Dutch company made headlines in 1908.

But the story of Wyoming’s petroleum really began with Washington Irving, author of “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.”

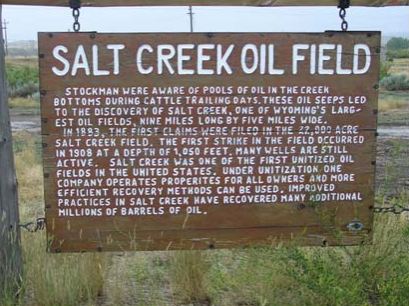

Discovered in 1908, Wyoming’s giant Salt Creek oilfield would produced more than 650 million barrels of oil over the next 100 years — and even more remains in the ground.

Irving, who also penned the short story “Rip Van Winkle,” became fascinated with the American Northwest in 1834 while writing about John Jacob Astor’s fur trading empire. Irving met explorer Capt. Benjamin Bonneville, whose exploits inspired the writing of another book.

Using Bonneville’s notes and maps, Irving in 1837 published The Adventures of Captain Bonneville: or, Scenes beyond the Rocky Mountains of the Far West. The widely read account of the four-year expedition featured details of life on the fur-trapping trail.

In what would become the Wyoming Territory, Bonneville made an 1832 trip down the Popo Agie River and noted seeing natural oil seeps. “In this neighborhood, the captain made search for ‘the great Tar Spring,’ one of the wonders of the mountains, the medicinal properties of which he had heard extravagantly lauded by the trappers,” Irving wrote.

The Salt Creek-Midwest field in Wyoming brought laws allowing companies to pool their interests and let a single company efficiently operate (drill, pump, and maintain) oil production.

“After a toilsome search, his expedition found a tar-like substance at the foot of a sand-bluff, a little east of the Wind River Mountains, where it exuded in a black, sticky stream,” Irving added.

Capt. Bonneville’s men, “hastened to collect a quantity of it, to use as an ointment for the galled backs of their horses, and as a balsam for their own pains and aches.” Irving added.

“From the description given of it, it is evidently the bituminous oil, called petroleum or naphtha, which forms a principal ingredient in the potent medicine called British Oil,” Irving explained. “In New York, it is called Seneca Oil, from being found near the Seneca lake.”

Tar Springs and Salt Creek

Tales of the “Great Tar Spring” would lead to Wyoming’s earliest hand-dug oil wells during the Civil War.

“The first recorded oil sale in Wyoming occurred along the Oregon Trail when, in 1863, enterprising entrepreneurs sold oil as a lubricant to wagon-train travelers” explains Wyohistory.org. “The oil came from Oil Mountain Springs some 20 miles west of present-day Casper.”

Indians had long known where oil could be found floating on the surface of Salt Creek, 20 miles north of Casper, Wyoming.

Meanwhile, America continued to grow westward, encouraged by periodic, if transitory, gold rushes. Growing consumer demand for kerosene lamp fuel brought the search for oil.

By 1867, the Union Pacific Railroad reached the easternmost boundary of the Wyoming Territory, spawning new towns all along its route. Because the right of way included substantial land grants on each side of the tracks, railroads were very much in the real estate business and promoted settlement in order to develop their property.

Still, by 1870 the pioneer population of Wyoming was just over 9,000 in a territory of 97,809 square miles.

The government owned almost half of the territory and encouraged development of mineral resources in these public lands through the federal Placer Act. Back East, declining production from Pennsylvania oilfields prompted the young petroleum industry to look westward.

First Drilled Wyoming Oil Well

Mike Murphy was a Pennsylvania-born Irishman who had come to the Nebraska Territory in 1854 as a land surveyor. He served in the territorial legislature until being lured to Colorado in search of gold in 1859. Murphy went to Montana looking for gold, and by 1876 he was off to the Black Hills, still prospecting.

When he returned to Wyoming in 1883, Murphy and his brother Frank bought an oil lease from Dr. George B. Graff — on the very site of Capt. Bonneville’s “great tar spring.” The Murphy brothers drilled for oil and found it at 300 feet in what would become known as the Chugwater formation.

The historic well’s oil was sold to the Union Pacific to lubricate railcar axles. News spread quickly and inspired others to stake their own “placer” mineral claims on promising sites. One of these sites was the Salt Creek valley area north of old Ft. Caspar, which would one day yield millions of barrels of oil.

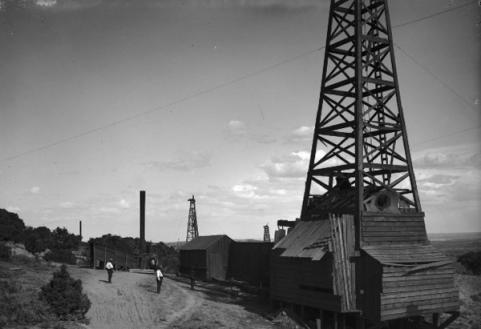

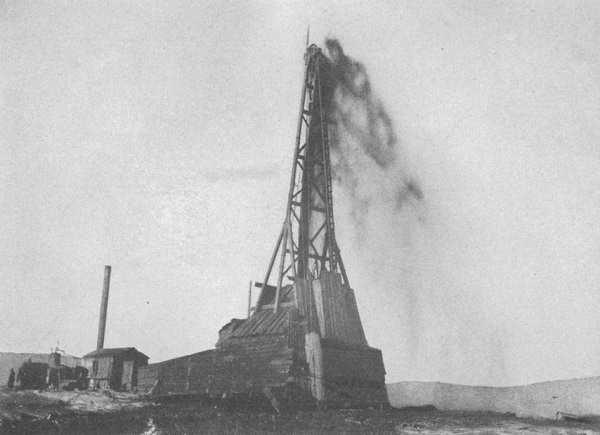

Development of the Salt Creek oilfield began in the late 1880s continued through the 1930s. Above is an Atlantic and Pacific Oil Company well circa 1903. Photo by J.E. Stimson, courtesy Wyoming State Archives.

Placer claims on government lands could be filed in 20-acre blocks by an individual or 160 acres by an “association” of eight individuals. For the claimant to be granted a legitimate patent on the land, the law required drilling a well, at least $500 in improvements, “oil in commercial quantity” (often disputed) and a $2.50 per acre fee.

Complicating the process was the government’s inclination to withdraw lands from the public domain. Competing legitimacy disputes, claim jumping, litigation, and even gun play were the natural byproducts of placer claims.

More Black Gold Discoveries

In 1887, perhaps lured by tales of Mike Murphy’s oil discovery, a tenacious but unsuccessful gold prospector by the name of Cy Iba returned from California with his four sons, two daughters, and their families. He began staking his own and “association” placer claims in Salt Creek. Iba and his family dug and timbered and staked and re-staked, eventually accumulating 30 claims in anticipation of one day selling valuable oil leases.

Meanwhile, Wyoming continued to grow with the railroads. The Fremont, Elkhorn & Missouri Valley Railroad pushed westward and delivered its first passengers to what would become Casper, Wyoming, in June 1888. Two years later, Iba came into conflict with a group of New York investors headed by H.D. Schoonmaker.

This group, “The Central Association of Wyoming,” had acquired its own placer claims. Iba sued and after several years of litigation, he settled for an 80-acre tract of the disputed “Jackass Claim.” Years later, the “Iba 80” would become one of the Salt Creek oilfield’s best producers.

First Wyoming Wildcatter

Noted Wyoming historian Mike Mackey in 1997 noted that Philip Martin Shannon was Wyoming’s first “legitimate” petroleum explorer because, “he plans on coming to Wyoming, drilling wells, refining the product, and finding a market for it.”

Shannon was a Civil War veteran and successful Pennsylvania oil businessman who first visited the area in 1884, Mackey wrote in a 1997 book about early developments of Wyoming’s oil industry.

With a small group of investors, he chose to drill on the northeast side of the Salt Creek activity, and began shipping equipment from Pennsylvania to the new Casper railroad station — still a 50-mile wagon haul from the proposed drilling site.

In August 1890, just one month after Wyoming became the 44th state, Shannon completed his first well. Even unrefined, the new state’s oil proved to be an excellent lubricant. The producing zone would become known as the Shannon sandstone.

“Dutch Well No. 1, December 1908, before well was capped,” noted the original caption for a well that produced 600 barrels of oil a day from 1,050 feet. Some Salt Creek wells produced from as shallow as 22 feet. Photo courtesy Department of Interior, USGS.

“Wyoming will become the greatest and wealthiest mineral producing state in the Union,” proclaimed Casper newspaper The Wyoming Derrick.

Within 20 months, Shannon and his associates had two producing wells, one dry hole, and a fourth well underway. Their only market for this unrefined lubricating oil was the railroads. Shannon negotiated agreements with the Fremont, Elkhorn & Missouri Valley Railroad as well as the Cheyenne & Northern.

Still, his oil had to be laboriously hauled in barrels by wagon to the railhead in Casper. The first delivery of 45 barrels took five days using a string team of 14 horses and three tandem wagons. In the distant East, a pessimistic Harper’s Magazine reported, “it is noticeable now that this oil excites little human interest, and interests still less capital.”

Salt Creek saw its first full scale water-flood development in 1962. In 2003, the field successfully completed a pilot carbon dioxide injection program.

Casper Refinery

To expand their markets, Shannon and his Pennsylvania investors began building a refinery in Casper in 1894. Wyoming’s population had grown to over 62,000. Within a year, the new refinery was able to produce 100 barrels a day of 15 different grades of lubricant, from “light cylinder oil” to heavy grease.

Shannon and his associates incorporated as the Pennsylvania Oil and Gas Company with 6,000 shares of stock. The company’s assets included the Casper refinery and placer claims on over 3,000 acres of the north perimeter of Salt Creek.

By 1904, the Pennsylvania Oil and Gas Company owned 14 small wells, each producing ten to 40 barrels per day – more than the Casper refinery or the market could accommodate.

Despite a growing population (1900 census counted 92,531) and improved railroad access, transportation costs meant that Wyoming oil could not successfully compete for the distant eastern markets. The Pennsylvania Oil and Gas Company struggled from the lack of infrastructure.

By October 1904, the company was sold to French and Belgian investors — who fared no better. The Casper refinery was closed.

Troubles with Placer Claims

Early petroleum companies faced many challenges trying to develop Wyoming’s exploration and production industry. The legitimacy problems of placer claims remained problematic for many years to come.

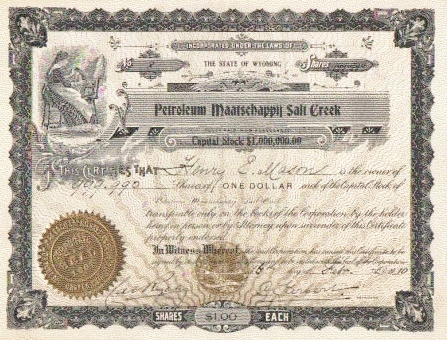

Wyoming’s first real petroleum boom began in 1908 when the Dutch-owned Petroleum Maatschappij Salt Creek Company completed the “Big Dutch” well about 40 miles north of Casper.

By 1912, every individual or company in the Salt Creek oilfield was either suing or being sued. Isolation from the petroleum-hungry eastern markets also endangered every oil venture.

Meanwhile, in a Wyoming valley on the border of Montana, a discovery well opened the giant Elk Basin oilfield on October 8, 1915. Drilled by the Midwest Refining Company, the wildcat well produced up to 150 barrels of oil a day of a high-grade, “light oil.”

The Elk Basin extended from Carbon County, Montana, into northeastern Park County, Wyoming. Geologist George Ketchum, who owned a small farm at Cowley, Wyoming, had first recognized the potential of the basin and explored the area in 1906 with C.A. Fisher.

Fisher was the first geologist to map sections of the Bighorn Basin southeast of Cody, Wyoming, where oil seeps had been found as early as 1883. The Wyoming discovery in unproved territory attracted speculators, investors, and new companies – including the Elk Basin United Oil Company.

Even with the advent of railroad tank cars, Wyoming oil could not compete in eastern markets because of transportation costs. These early problems eventually yielded to the tenacity of the stubborn oilmen who confronted them. In 1920, the “Oil and Gas Leasing Act” finally provided relief from the legal wrangling over placer claims.

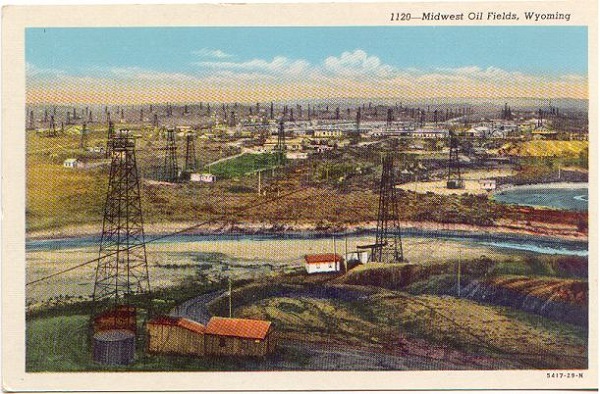

In Midwest, “the heart of central Wyoming, you will discover its history has a taste of the oilfield pioneers and new oilfield related industries.”

Salt Creek Oil Boom

Wyoming’s first real oil boom would have to wait until the Dutch-owned Petroleum Maatschappij Salt Creek Company’s well erupted on October 23, 1908, bringing a new flood of entrepreneurs and investors.

Although Salt Creek was known to be productive, the central Salt Creek dome received little attention until noted Italian geologist Dr. Cesare Porro recommended the drilling site to Petroleum Maaschappij in 1906. Drillers J.E. Stock and his father, working for the English company Oil Wells Drilling Syndicate, completed the well at 1,050 feet with production of 600 barrels of oil a day.

Development of Salt Creek oilfield began in 1889 with the majority occurring between 1915 and 1930. U.S. Department of the Interior records indicate oil was found at depths as shallow as 22 feet in 1911.

Wyoming ‘s Salt Creek Oil Field Museum was founded in 1980 by author and historian Pauline L. Schultz (1915-2011), who received the U.S. National Humanities Medal in 2005.

By 1930, about one-fifth of all oil produced in the United States came from Salt Creek. More than 4,000 petroleum wells have since been drilled in the ten producing zones of the 22,000-acre field. In 2007 alone, Salt Creek produced almost three million barrels of oil.

A 2014 article posted by historian Tom Rea explained another aspect to the field’s story:

November 19, 1925 was a cold night for football in the oil boom town of Midwest, Wyoming. “Don’t Miss It,” the Casper Herald had advised the day before. “Something New, Football at Night, Casper vs. Midwest.”

“Floodlights,” the newspaper continued, would be “assisted by open gas flares for light and warmth — the roads are fine…”

Fine perhaps, Rea noted, but still dirt in 1925 and Midwest 40 miles north of Casper.

For the football game, Midwest Refinery Company electricians set up twelve floodlights of 1,000 candlepower each around the field, four more of 2,000 candlepower, and from the top of an oil derrick near the field, a huge searchlight swung its beam over the players and the crowd.

Rea’s account added that electricity had come to the oilfields around Midwest earlier in 1925, “when the company built an electric plant to power thousands of oil well pumps.”

Rea also noted in Boom, Bust, and After — Life in the Salt Creek Oil Field that new laws in the 1930s allowed companies to pool their interests and hire a single company to operate — drill, pump, and maintain — the fields.

Pauline Schultz’s Oil Museum

The Salt Creek oilfield would produced more than 650 million barrels of oil over the next 100 years — with even more remaining in the ground. Using advanced technologies, companies began injecting carbon dioxide into wells; the added pressure has kept oil flowing.

The Salt Creek Museum in Midwest displays artifacts and more than 4,000 photographs of the Salt Creek and Teapot Dome Naval Reserve No. 3 oilfields, illustrating the area’s history from 1889 to today, according to Curator Pauline L. Schultz, who was born on June 7, 1915, and died on October 30, 2011. She founded Midwest’s oil museum in 1980.

In 2007, Schultz was awarded a National Humanities Medal from President George W. Bush, and her National Endowment for the Humanities biography has extensive oil history preservation accomplishments. Her father — born in Titusville, Pennsylvania, home of the first U.S. oil well — initially moved the family to Midwest oilfields in 1924.

The Salt Creek Museum collection includes a complete set of Midwest Refining Company books from 1920 to 1930. The Salt Creek field, about 40 miles north of Casper, was once among the largest light crude oilfields in the world.

The oilfield became famous for its gushers and a pipeline to a Casper refinery was built in 1911. Salt Creek was surpassed in the 1920s by the nearby Teapot Dome field — source of a financial scandal during the Warren G. Harding administration.

Buffalo Bill’s Oil Company

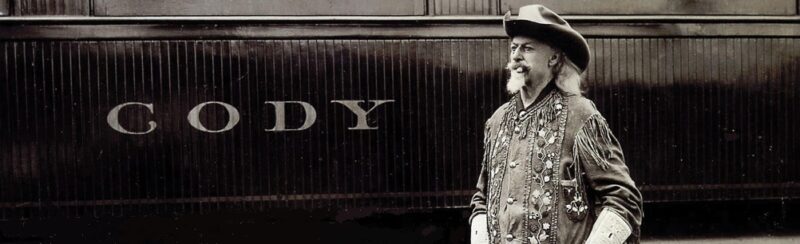

Col. William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, already famous for his Wild West Show, tried his luck in the Wyoming oil patch — as did an arctic explorer of more dubious fame.

Col. W.F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody promoted an oilfield on the Shoshone Anticline near Cody, Wyoming. Circa 1915 photo courtesy Buffalo Bill Center of the West.

In 1902 and and again in 1910, Cody formed oil companies and filed oil placer claims south of Cody. Although he promoted his “Bonanza Oil District” to potential investors, his efforts ended in dry holes.

Read about Col. Cody’s petroleum adventures in Buffalo Bill Shoshone Oil Company.

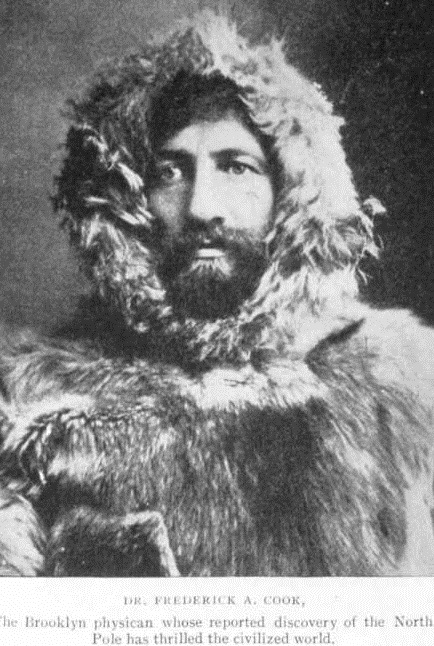

Infamous explorer of North Pole Dr. Frederick Cook, who fraudulently promoted Wyoming oil ventures in 1917.

In 1917, the discredited Arctic expedition leader Dr. Frederick Albert Cook conducted geological explorations in Wyoming for his newly formed company, the Texas Eagle Oil Company of Fort Worth.

The controversial North Pole explorer’s fraudulent claims led to several failed oil company ventures, a mail fraud conviction, and jail time. Learn more in Arctic Explorer turns Oil Promoter.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Adventures of Captain Bonneville: or, Scenes beyond the Rocky Mountains of the Far West, 1837 (reprint, 2009); Black Gold, Patterns in the Development of Wyoming’s Oil Industry (1997); The Salt Creek Oil Field: Natrona County, Wyo., 1912 (reprint, 2017); Kettles and Crackers – A History of Wyoming Oil Refineries

(2016). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information: Article Title – “First Wyoming Oil Well.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/first-wyoming-oil-well. Last Updated: October 17, 2024. Original Published Date: December 1, 2008.