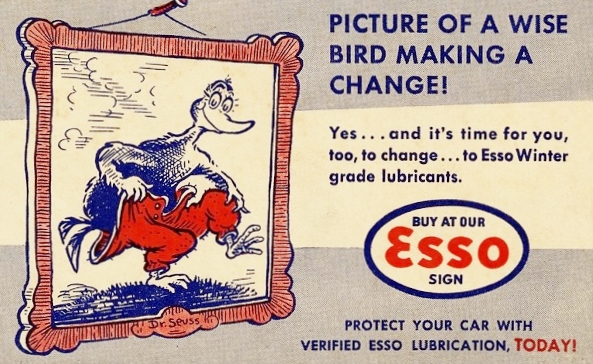

January 14, 1928 – Dr. Seuss begins illustrating Standard Oil Ads –

New York City’s Judge magazine published its first cartoon drawn by Theodor Seuss Geisel — who would develop his skills as “Dr. Seuss” while working for the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey.

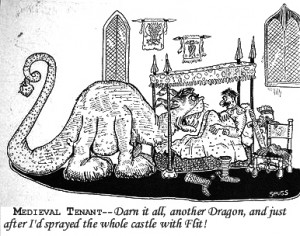

In the 1928 cartoon that launched his professional career as an advertising illustrator, Geisel drew a peculiar dragon trying to dodge Flit, a popular bug spray of the day. “Quick, Henry, the Flit!” soon became a catchphrase nationwide. Flit was one of Standard Oil of New Jersey’s many consumer products derived from petroleum.

During the Great Depression, Theodor S. Geisel — Dr. Seuss — created popular advertising campaigns for the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey.

Hundreds of Geisel’s fanciful critters populated Standard Oil advertisements throughout the Great Depression, providing him with much-needed income. Ad campaigns included cartoon creatures for Esso gasoline, lubricating oils, and Essomarine engine oil and greases. The children’s book author later acknowledged his Standard Oil experience, “taught me conciseness and how to marry pictures with words.”

Learn more in Seuss I am, an Oilman.

January 14, 1954 – Oil discovery in South Dakota

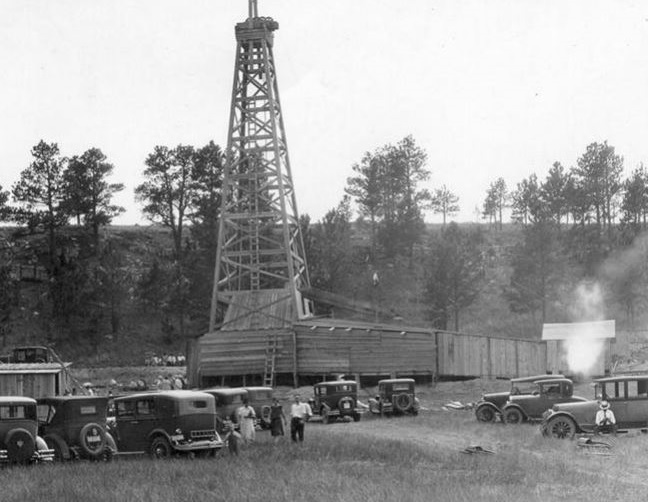

A Shell Oil Company wildcat well in Harding County, South Dakota, began producing oil from about 9,300 feet deep, revealing South Dakota’s first oilfield. Drilled in what proved to be the Buffalo field, the well produced more than 341,000 barrels of oil in five decades.

This cable-tool rig in 1929 drilled an expensive “dry hole” in Custer County of the “Mount Rushmore State.” Photo courtesy South Dakota Department of Environment and Natural Resources.

Although South Dakota had a long history of petroleum exploration (natural gas production began in 1899), Harding County produced most of the state’s oil. Since the 1980s, South Dakota oil production has ranged between about 1 million and 2 million barrels of oil per year, according to the U.S. Energy Information Agency (EIA). Oil production in 2023 fell to 929,000 barrels, the lowest level since before 1981.

Modern Bakken shale production has not extended into South Dakota, but other oil-producing formations have been found (also see First North Dakota Oil Well).

January 17, 1911 – North Texas Boom begins at Electra

The Producers Oil Company discovered the Electra oilfield in North Texas, bringing the first commercial oil production to Wichita County. The Waggoner No. 5 well produced 50 barrels per day from a depth of 1,825 feet on land owned by local rancher William Waggoner, who had found traces of oil while drilling a water well for his cattle.

Named after rancher William Waggoner’s daughter, Electra, would become the “Pump Jack Capital of Texas.” Photo by Bruce Wells.

“At first, there weren’t any cars, and about the only thing oil was good for was to help repel chicken house mites,” noted a county historian about the discovery well, which attracted the attention of many independent producers. On April 1, the nearby Clayco No. 1 gusher would send the oil fortunes of Electra further skyward.

January 18, 1919 – Congregation rejects drilling in Cemetery

World War I had ended two months earlier as oil production continued to soar in North Texas. Reporting on “Roaring Ranger” oilfields, the New York Times noted that speculators had offered $1 million for rights to drill in the Merriman Baptist Church cemetery, but the congregation could not be persuaded to disturb the interred.

“Lone Star Bonanza, the Ranger Oil Boom of 1917-1923,” photograph of a North Texas church cemetery by Robert Vann.

Posted on a barbed-wire fence surrounding the graves not far from producing oil wells, a sign proclaimed, “Respect the Dead.” Today, the cemetery — and a new church — can be found three miles south of Ranger.

Learn more in Oil Riches of Merriman Baptist Church.

January 19, 1922 – USGS predicts Oil Shortage, Again

The U.S. Geological Survey predicted America’s oil supplies would run out in 20 years. It was not the first or last false alarm. Warnings of shortages had been made for most of the 20th century, according to geologist David Deming of the University of Oklahoma. His 1950 report, A Case History of Oil-Shortage Scares, documented six claims prior to 1950 alone.

Among the end of oil supplies predictions named in the report: The Model T Scare of 1916; the Gasless Sunday Scare of 1918; the John Bull (United Kingdom) Scare of 1920-1923; the Ickes (Interior Secretary Harold Ickes) Petroleum Reserves Scare of 1943-1944; and the Cold War Scare of 1946-1948. Predictions of U.S. oil shortages began as early as 1879, when the Pennsylvania state geologist said remaining oil supplies would keep kerosene lamps burning for just four more years.

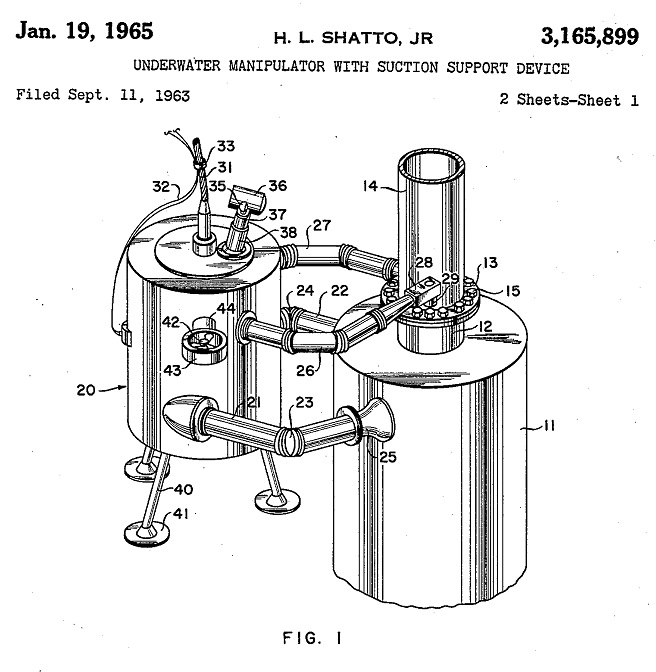

January 19, 1965 – “Underwater Manipulator” patented

Howard Shatto Jr. received a 1965 U.S. patent for his “underwater manipulator with suction support device.” His concept led to the modern remotely operated vehicle (ROV) now used most widely by the offshore petroleum industry. Shatto helped make Shell Oil Company an early leader in offshore oilfield technologies.

Howard Shatto Jr. would become “a world-respected innovator in the areas of dynamic positioning and remotely operated vehicles.”

Underwater robot technology can trace its roots to the late 1950s, when Hughes Aircraft developed a Manipulator Operated Robot — Mobot — for the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission. Beginning in 1960, Shell Oil began transforming the landlocked Mobot into a marine robot, “basically a swimming socket wrench,” noted one engineer.

In his 1965 patent — one of many he received — Shatto explained how his robot could install production equipment at greater depths than divers could safely work. The ROV inventor also would become known as the offshore industry’s father of dynamic positioning.

Learn more in ROV – Swimming Socket Wrench.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Theodor Geisel: A Portrait of the Man Who Became Dr. Seuss (2010); Early Texas Oil: A Photographic History, 1866-1936

(2000); Ranger, Images of America

(2010); Diving & ROV: Commercial Diving offshore (2021); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2009); Portrait in Oil: How Ohio Oil Company Grew to Become Marathon

(1962); Ohio Oil and Gas, Images of America

(2008); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.