January 12, 1904 – Henry Ford sets Speed Record –

Seeking to prove his cars were built better than most, Henry Ford set a world land speed record on a frozen Michigan lake. At the time, the Ford Motor Company was struggling to get financial backing for its first car, the Model T. The automotive pioneer drove his No. 999 Ford Arrow across Lake St. Clair, which separates Michigan and Canada, at a top speed of 91.37 mph.

The Ford No. 999 was powered by an 18.8-liter inline four-cylinder engine that could produce up to 100 hp. Image courtesy Henry Ford Museum.

“The lake played an important role in automobile testing in the early part of the century,” explains Mark Dill in Racing on Lake St. Clair. “Roads were atrocious, and there were no speedways.”

Six years after Henry Ford’s record run, the Detroit Free Press reported “Auto beats flyer at its own game” when another Ford racer outpaced an ice boat on Lake St. Clair. Photo courtesy Model T Ford Club of America.

Lake St. Clair provided a flat, smooth surface that was conditioned with hot cinders to improve traction, according to Dill, author of The Legend of the First Super Speedway — the Battle for the Soul of American Auto Racing. Henry Ford’s 91 mph world speed record took place four years after America’s first auto show. The Blue flame, a natural gas-powered rocket car, reached a world speed record of 630 mph in 1970.

January 12, 1919 – North Louisiana Oilfield Discovery

Claiborne Parish made headlines when Consolidated Progressive Oil Company completed a giant oilfield discovery well four miles west of Homer in northern Louisiana. “Homer was a happening place, and all people could think about was oil,” reported Wesley Harris in Oil Boom Overwhelmed Homer.

“Imagine Homer’s courthouse square with no place to park, nowhere to eat, and business establishments packed to overflowing,” Harris added. Homer’s oil boom followed another giant oilfield discovery about 50 miles west at Caddo-Pines in 1905 (see First Louisiana Oil Wells).

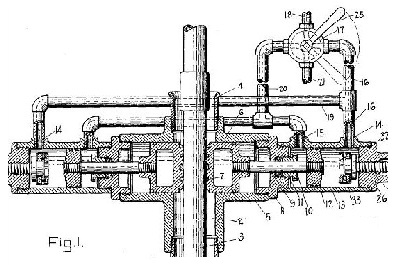

January 12, 1926 – Texans patent Ram-Type Blowout Preventer

Seeking to end dangerous and wasteful oil gushers, James Abercrombie and Harry Cameron patented a hydraulic ram-type blowout preventer (BOP). About four years earlier, Abercrombie had sketched out the design on the sawdust floor of Cameron’s machine shop in Humble, Texas. Petroleum companies embraced the new technology, which would be improved in the 1930s.

James Abercrombie’s design used hydrostatic pistons to close on the drill stem. His improved blowout preventer set a new standard for safe drilling.

First used during the Oklahoma City oilfield boom, the BOP helped control production of the highly pressurized Wilcox sandstone (see World-Famous “Wild Mary Sudik”). The American Society of Mechanical Engineers recognized the Cameron Ram-Type Blowout Preventer as an “Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark” in 2003. Learn more in Ending Oil Gushers – BOP.

January 14, 1928 – Dr. Seuss begins illustrating Standard Oil Ads

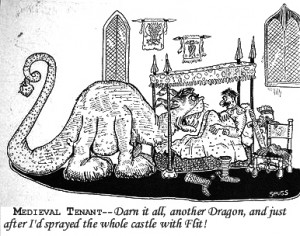

New York City’s Judge magazine published its first cartoon drawn by Theodor Seuss Geisel — who would develop his skills as “Dr. Seuss” while working for the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey.

In the 1928 cartoon that launched his professional career as an advertising illustrator, Geisel drew a peculiar dragon trying to dodge Flit, a popular bug spray of the day. “Quick, Henry, the Flit!” soon became a catchphrase nationwide. Flit was one of Standard Oil of New Jersey’s many consumer products derived from petroleum.

During the Great Depression, Theodor S. Geisel — Dr. Seuss — created many advertising campaigns for the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey. Image courtesy University of California San Diego Library.

Hundreds of Geisel’s fanciful critters populated Standard Oil advertisements throughout the Great Depression, providing him with much-needed income. Ad campaigns included cartoon creatures for Esso gasoline, lubricating oils, and Essomarine engine oil and greases.

The children’s book author later acknowledged his Standard Oil experience “taught me conciseness and how to marry pictures with words.” Learn more in Seuss I am, an Oilman.

January 14, 1954 – Oil discovery in South Dakota

A Shell Oil Company wildcat well in Harding County, South Dakota, began producing oil from about 9,300 feet deep, revealing South Dakota’s first oilfield. Drilled in what proved to be the Buffalo field, the well produced more than 341,000 barrels of oil in five decades.

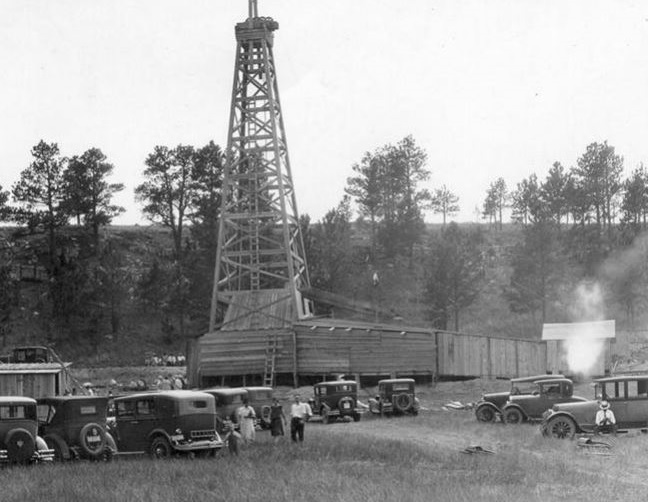

This cable-tool rig in 1929 drilled a “dry hole” in Custer County of the “Mount Rushmore State.” Photo courtesy South Dakota Department of Environment and Natural Resources.

Although South Dakota had a long history of petroleum exploration (natural gas production began in 1899), Harding County produced most of the state’s oil. Since the 1980s, South Dakota oil production has ranged between about 1 million and 2 million barrels of oil per year, according to the U.S. Energy Information Agency (EIA). Oil production in 2023 fell to 929,000 barrels, the lowest level since before 1981.

Modern Bakken shale production has not extended into South Dakota, but other oil-producing formations have been found (also see First North Dakota Oil Well).

January 17, 1911 – North Texas Boom begins at Electra

The Producers Oil Company discovered the Electra oilfield in North Texas, bringing the first commercial oil production to Wichita County. The Waggoner No. 5 well produced 50 barrels per day from a depth of 1,825 feet on land owned by local rancher William Waggoner, who had found traces of oil while drilling a water well for his cattle.

Named after rancher William Waggoner’s daughter, Electra would become the “Pump Jack Capital of Texas.” Photo by Bruce Wells.

“At first, there weren’t any cars, and about the only thing oil was good for was to help repel chicken house mites,” noted a county historian about the discovery well, which attracted the attention of many independent producers. On April 1, the nearby Clayco No. 1 gusher would send the oil fortunes of Electra further skyward.

January 18, 1919 – Congregation rejects drilling in Cemetery

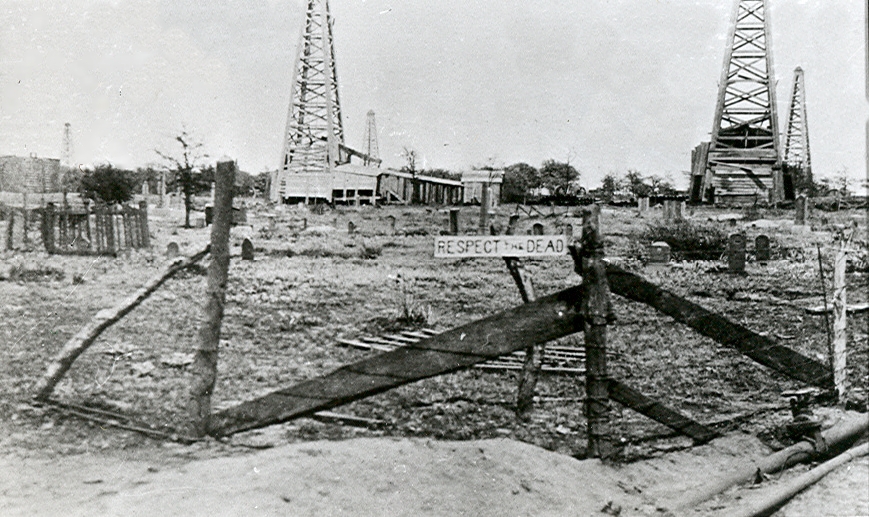

World War I had ended two months earlier as oil production continued to soar in North Texas. Reporting on the “Roaring Ranger” oilfields, the New York Times noted that speculators had offered $1 million for rights to drill in the Merriman Baptist Church cemetery, but the congregation could not be persuaded to disturb the interred.

“Lone Star Bonanza, the Ranger Oil Boom of 1917-1923,” the North Texas church cemetery photo by Robert Vann about three miles south of the “Roaring Ranger” oilfield discovery.

Posted on a barbed-wire fence surrounding the graves not far from producing oil wells, a sign proclaimed, “Respect the Dead.” The Merriman cemetery — and a new church — can be visited three miles south of Ranger. Learn more in Oil Riches of Merriman Baptist Church.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Legend of the First Super Speedway – the Battle for the Soul of American Auto Racing (2020); I Invented the Modern Age: The Rise of Henry Ford (2014); Drilling Technology in Nontechnical Language

(2012); Theodor Geisel: A Portrait of the Man Who Became Dr. Seuss

(2010); The Bakken Goes Boom: Oil and the Changing Geographies of Western North Dakota

(2016); Early Texas Oil: A Photographic History, 1866-1936

(2000); Ranger, Images of America

(2010); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2026 Bruce A. Wells.