Horace Horton’s Spheres

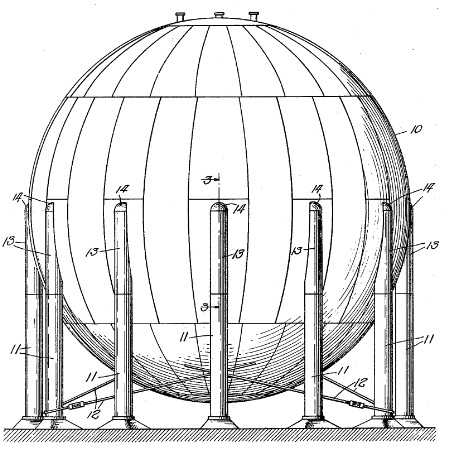

Chicago Bridge & Iron Company in 1923 began erecting giant, spherical pressure vessels.

Seen from the highway, the spheres look like massive eggs or fanciful Disney architectural projects. A 19th-century iron bridge manufacturer from Chicago conceived the idea for these globes — at first made by riveting together wrought iron plates. Modern highly pressured vessels are vital for storing and transporting liquified natural gas (LNG).

Chicago Bridge & Iron Company (CB&I) officially named “Hortonspheres” — also called Horton spheres — after Horace Ebenezer Horton (1843-1912), the company founder and designer of water towers and rounded storage vessels. His son George would patent designs standing among the great innovations to come to the oil patch.

Hortonspheres, the trademarked name of massive containers for storing and transporting liquified natural gas (LNG), were invented by a bridge-building company.

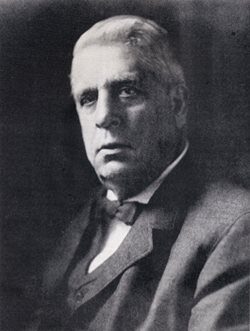

Horace Horton grew up in Chicago, where he became skilled in mechanical engineering. He was 46 years old when he formed CB&I in 1889. His company prospered, building seven bridges across the Mississippi River.

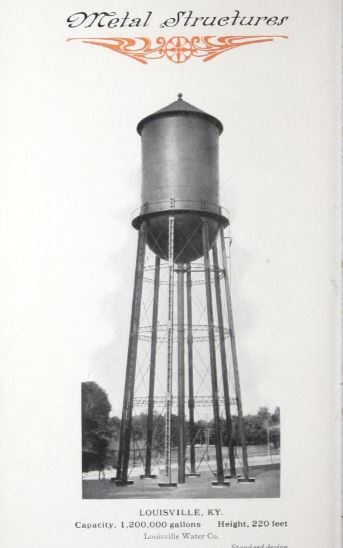

Horton then expanded the company’s Washington Heights, Illinois, fabrication plant to begin manufacturing water tanks. It was a decision that would bring water towers to hundreds of towns.

Horace Ebenezer Horton (1843-1912) founded the company that would build the world’s first “field-erected spherical pressure vessel.”

CB&I erected its first elevated water tank in Fort Dodge, Iowa, in 1892, according to the company, which has noted that “the elevated steel plate tank was the first built with a full hemispherical bottom, one of the company’s first technical innovations.”

When Horton died in 1912, his company was just getting started. Soon, the company’s elevated towers were providing efficient water storage and pipeline pressure that benefited many cities and towns. CB&I’s first elevated “Watersphere” tank was completed in 1939 in Longmont, Colorado.

Improved Oilfield Structures

The company brought its steel plate engineering expertise to the oil and natural gas industry as early as 1919, when it built a petroleum tank farm in Glenrock, Wyoming, for Sinclair Refining Company (formed by Harry Sinclair in 1916).

Horace E. Horton’s company designed spherical storage vessels for his Chicago Bridge & Iron Company. Photo courtesy CB&I.

CB&I’s innovative steel plate structures and construction technologies proved a great success. The company left bridge building entirely to supply the petroleum infrastructure market.

A spherically bottomed water tower shown in the Chicago Bridge & Iron Company 1912 sales book.

Newly discovered oilfields in Ranger, Texas, in 1917 and Seminole, Oklahoma, in the 1920s were straining the nation’s petroleum storage capacity. A lack of pipelines and storage facilities in booming West Texas was a big problem.

In the Permian Basin, an exploration company’s executives were desperate to store soaring oil production. They hired engineers to design an experimental tank capable of holding up to five million barrels of oil at Monahans, Texas. Construction in early 1928 took three months working 24 hours a day.

Roxana Petroleum Company’s massive storage structure used concrete-coated earthen walls 30 feet tall. The oil reservoir was covered with a cedar roof to slow evaporation.

But when no solution could be found for leaking seams, the oil storage attempt was abandoned.The concrete oval, which briefly became a water park in 1958, later became home to Monahans’ Million Barrel Museum.

By 1923, CB&I’s storage innovations like its “floating roof” oil tank had greatly increased safety and profitability as well as setting industry standards. That year the company built its first Hortonsphere in Port Arthur, Texas.

Liquefied Natural Gas

Soon, spherical vessels of all sizes were being used for storage of compressed gases such as propane and butane. Hortonspheres also hold liquefied natural gas (LNG) produced by cooling natural gas at atmospheric pressure to minus 260 degrees Fahrenheit, at which point it liquefies.

As an iconic engineering example of form following function, the sphere is the ideal shape for a vessel that resists internal pressure.

In the first Port Arthur installation and up until about 1941, the component steel plates were riveted; thereafter, welding allowed for increased pressures and vessel sizes. As metallurgy and welding advances brought tremendous gains in Hortonspheres’ holding capacities, they also have proven to be an essential part of the modern petroleum refining business.

CB&I constructed fractionating towers for many petroleum refineries, beginning with Standard Oil of Louisiana at Baton Rouge in 1930. The company also built a giant, all-welded 80,000-barrel oil storage tank in New Jersey.

Since its first sphere in 1923, Chicago Bridge & Iron by 2013 fabricated more than 3,500 Hortonspheres for worldwide markets in capacities reaching more than three million gallons — reportedly the world’s top spherical storage container builder.

Poughkeepsie Hortonsphere

Fascinated by geodesic domes and similar structures, Jeff Buster discovered a vintage Hortonsphere in Poughkeepsie, New York. In 2012 he contacted the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation.

A Hortonsphere viewed in 2012 from the “Walkway over the Hudson” in Poughkeepsie, New York. It was dismantled in 2013. Photo courtesy Jeff Buster.

Buster wanted the agency to save Horton’s sphere at the corner of Dutchess and North Water streets. He asked that an effort be made “to preserve this beautiful and unique ‘form following function’ structure, which is in immediate risk of being demolished.”

Buster posted a photo of the Poughkeepsie Hortonsphere on a website devoted to geodesic domes. “The jigsaw pattern of steel plates assembled into this sphere is unique,” he wrote.

“The layout pattern is repeated four times around the vertical axis of the tank,” Buster added. “With the rivets detailing the seams, the sphere is extremely cool and organic feeling.”

Although the steel tank, owned by Central Hudson Gas and Electric Company, was demolished in late 2013, Buster’s photo has helped preserve its oil patch legacy.

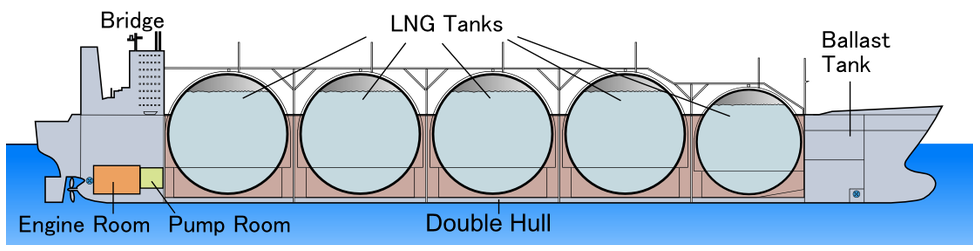

Liquified Natural Gas at Sea

Sphere technology became seaborn as well. On February 20, 1959, after a three-week voyage from Lake Charles, Louisiana, the Methane Pioneer — the world’s first LNG tanker — arrived at the world’s first LNG terminal at Canvey Island, England.

Ships began transporting liquified natural gas as early as 1959. Modern LNG tankers are many times larger and protected with double hulls.

The Methane Pioneer, a converted World War II liberty freighter, contained five, 7,000-barrel aluminum tanks supported by balsa wood and insulated with plywood and urethane. The 1959 successful voyage across the Atlantic demonstrated that large quantities of liquefied natural gas could be transported safely across the ocean.

Most modern LNG carriers have between four and six tanks on the vessel. New classes have a cargo capacity of between 7.4 million cubic feet and 9.4 million cubic feet. Each ship is equipped with its own re-liquefaction plant.

In 2015 — about 100 years after Horace Ebenezer Horton died — Mitsubishi Heavy Industries announced constructing of the next-generation LNG carriers to transport the shale gas produced in North America. Rapid growth of U.S. natural gas production came from hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) of shale formations in North Dakota and other states.

In 2023, there were 772 LNG storage vessels worldwide, according to Statista.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); Sheer Will: The Story of the Port of Houston and the Houston Ship Channel (2014). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2023 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Horace Horton’s Spheres.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/transportation/hortonspheres/. Last Updated: September 17, 2024. Original Published Date: December 14, 2016.