Public fascination with Mid-Continent “black gold” discoveries briefly switched to natural gas in 1906.

As petroleum exploration wells reached deeper by the early 1900s, highly pressurized natural gas formations in Kansas and the Indian Territory challenged well-control technologies of the day.

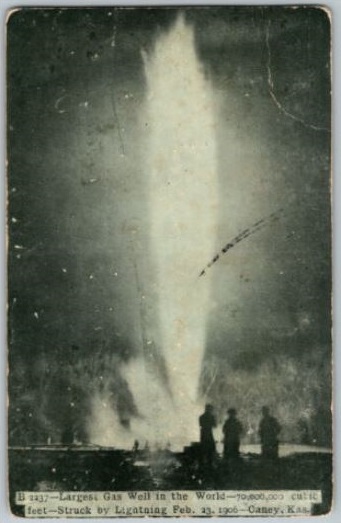

Ignited by a lightning bolt in the winter of 1906, a natural gas well at Caney, Kansas, towered 150 feet high and at night could be seen for 35 miles. The conflagration made headlines nationwide, attracting many exploration and production companies to Mid-Continent oilfields even as well control technologies tried to catch up.

A Colorado publishing company’s postcard of the Caney, Kansas, highly pressurized natural gas well struck by lightning on February 23, 1906.

Newspapers as far away as Los Angeles regularly updated readers as the technologies of the day struggled to put out the Caney well fire, “which defied the ingenuity of man to subdue its roaring flames.”

The Denver publisher Williamson Haffner Company printed and sold postcards with the caption: “Largest Gas Well in the World — 70,000,000 cubic feet — Struck by Lightning Feb. 23, 1906 — Caney, Kas.” The reverse side of one postcard sent to Attica, Indiana, on October 24, 1907, noted: “We came down here today in a carriage, 25 miles, going back in the morning. From your Mother.”

With effective oilfield firefighting technologies still evolving, it would take five weeks to bring the Kansas town’s wild well under control. It took several attempts to smother the column of fire using specially fabricated steel hoods.

Oil and Natural Gas Discoveries

By the early 1900s, abundant natural gas supplies were attracting manufacturing industries to the Midwest. Major gas fields had been discovered between Caney and Bartlesville in Indian Territory (the state of Oklahoma in 1907). About 20 miles apart, the towns were connected by the Caney River.

Caney had been founded in 1869 as a trading post. Osage Indians frequently camped along the Little Caney River before being moved to present-day Osage County, Oklahoma.

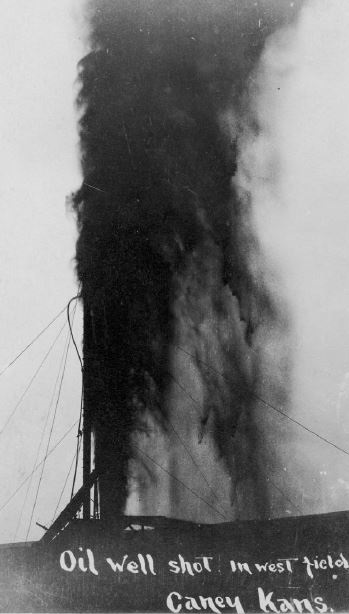

Intrepid oilfield workers struggled to cap the blazing well using cranes and specially fabricated steel hoods. Photo courtesy Jeff Spencer.

“Chief Black Dog of the Osage tribe blazed a trail ’30 horses wide’ along the Kansas-Indian Territory border and set a camp of the Osage tribe in the Caney vicinity,” reported the City of Caney. The region’s petroleum industry came to life thanks to the man who helped found Bartlesville.

In 1875, Jacob Bartles operated a trading post on the Caney River in the Cherokee Nation. He employed two ambitious young men, George Keeler and William Johnstone. They later started their own general store on the other side of the river. In 1897 — a decade before Oklahoma statehood — the two men drilled a well at a river bend near their store.

The Nellie Johnstone No. 1 well, today surrounded by Bartlesville’s Discovery One Park, was the First Oklahoma Oil Well. Several very large natural gas well completions were made during the early 1900s between Caney, Kansas, and Bartlesville, Indian Territory, according to oil patch historian and petroleum geologist Jeff Spencer of Bellville, Texas.

Kansas Boom Town

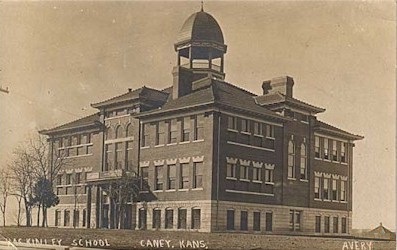

Oil wells completed near Caney by 1903 resulted in oil tank farms, oil pumping stations and refineries being built in the area. Caney soon added several brick and glass plants fueled by natural gas.

“Glass manufacturing arrived in southeastern Kansas to take advantage of the large gas supplies,” Spencer noted in a 2007 article for the Petroleum History Institute (PHI) journal Oil-Industry History. Between 1902 and 1906, three glass factories opened near Caney.

However, the risks of highly pressurized gas formations became evident on February 23, 1906, when lightning struck the New York Oil and Gas Company’s derrick four miles outside Caney.

An undated postcard of an early oil well near Caney, Kansas, after it has been “shot” with nitroglycerin. Photo courtesy Jeff Spencer.

The well had reached about 1,430 feet deep after three weeks of drilling. Estimates of the well’s gas flow at the time of the lightning strike were over 30 million cubic feet of gas a day. By the time the fire was extinguished, the flow had reached as high as 70 million cubic feet of gas a day.

“Residents of Caney could read their newspapers at night by the glow of the burning gas well and even though it was early March, trees and flowers bloomed near the well site,” noted Spencer, who updated his article in 2012.

“Nearby towns of Independence, Coffeyville, Bartlesville, and Caney all claimed the attraction,” he reported. “Excursion trains brought thousands of tourists to the site.”

Citing a 1907 article discovered in The Wide World Magazine, Spencer described efforts to extinguish the blazing well, quoting author W.H. Cotton: “Appliances hitherto generally used in such emergencies were useless; some new schemes must be devised to cope with the situation.”

A specially welded iron hood was made to smother the flaming well using a crane to lower the heavy, unwieldy device. Several unsuccessful attempts were made with this first hood. A second hood then was constructed and lowered over the flame. It too failed, as did several attempts with a third.

“A fourth hood had been built and delivered, but it was cumbersome, owing to its excessive weight,” Spencer explained in the PHI article. A larger crane would be needed.

Success finally came after retrying the third hood. Hundreds had watched these experiments of oilfield well control technology. “All was breathless silence. Cameras were previously focused, and every possible preparation made to witness the event so looked for,” W.H. Cotton reported.

Meanwhile, an article in the Chanute Tribune reported speculation that Caney’s gas well fire had been permitted to burn as a publicity stunt.

Cahege Oil & Gas Company

More petroleum companies explored around Caney. As would happen many times in the industry’s competitive boom-and-bust cycles, few would prosper. Many more would not survive.

Petroleum wealth brought industries to Caney, Kansas, and helped build McKinnley School, pictured circa 1909.

Some historians have noted that a young Harry F. Sinclair drilled his first oil well at Caney in 1905, before making his fortune at the Glenn Pool oilfield near Tulsa a few years later (see Making Tulsa the Oil Capital).

Among the quickly organized exploration ventures seeking riches at Caney, the Cahege Oil & Gas Company of Carrollton, Missouri, in 1904 leased 15,000 acres. Local newspaper business editors endorsed the company’s exploration effort, proclaiming, “We believe the stock-holders have a good thing ahead.”

However, the two wells drilled by Cahege Oil & Gas Company did not produce commercial quantities and the company failed, going broke the year before Carney’s headline and postcard-making gas well fire.

Another small Kansas town prospered far more than Caney, thanks to petroleum. On October 6, 1915, the Stapleton No. 1 oil well in El Dorado utilized the increasingly important science of geology to reveal a massive Mid-Continent oilfield. The El Dorado discovery led to another Kansas Oil Boom.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Caney, Kansas: The Big Gas City (1985); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); The Natural Gas Revolution: At the Pivot of the World’s Energy Future

(2013). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Kansas Gas Well Fire.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/technology/kansas-gas-well-fire. Last Updated: February 11, 2025. Original Published Date: October 24, 2016.