Making “wet gas” in early 20th century Oklahoma oilfields.

When Robert Galbreath and Frank Chesley completed their Ida Glenn No. 1 well on November 22, 1905, they revealed another giant oilfield south of Tulsa. The discovery well, drilled with cable-tool technology, struck oil-bearing sands at a depth of only 1,450 feet.

Production from Oklahoma’s latest giant field not only supplied Tulsa refineries, it brought other opportunities, including the commercial use of casinghead gas.

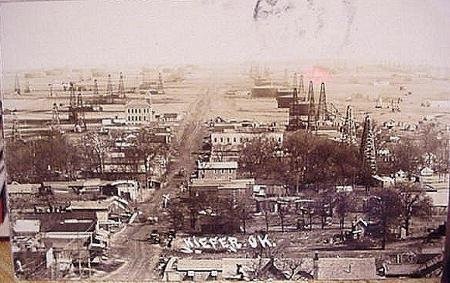

Twenty miles south of Tulsa, the railroad town of Kiefer was above the Glenn Pool oilfield. Circa 1909 photo courtesy Tulsa City-County Library.

Petroleum exploration and production companies had long known pumping oil unpredictably brought dissolved gases to the surface, where reduced pressure released highly flammable gas. Dangerous “kicks” of light hydrocarbon fumes at producing oil wells were routinely vented or ignited and flared off for safety.

Although flaring burned much of an oil well’s methane content, early 20th-century technologies made it possible to extract valuable condensates before the gas was wasted. Oilfield engineering advances enabled processing an oil well’s gaseous mix into a liquid, resulting in gasoline of between 40 and 60 octane.

The gasoline made from the well’s fumes became known as casinghead gas (or casing head gas), wet gas, drip gas, absorption gasoline, residue gas, condensation gasoline, white gas, natural gasoline, and other names.

Compared to the 86-octane gasoline distilled from petroleum by refineries, casinghead gas was more unstable, volatile, and dangerous to transport. The low-cost condensate gasoline still had commercial possibilities.

Glenn Pool Boom at Kiefer

In 1909, Douglas Warner “D.W.” Franchot opened the first of many casinghead gasoline plants spawned by the discovery of the Glenn Pool. A Yale graduate and Civil War veteran, he had been a successful Ohio oil producer.

Franchot chose a construction site at the railroad siding town of Kiefer, a new boom town, “where there could be found every known method or device for separating a man and his money,” according to the newspaper Mounds Enterpriser.

D.W. Franchot & Company was established in Kiefer, Oklahoma, because the booming Glenn Pool oil town was on the St. Louis & San Francisco Railway.

But for D.W. Franchot & Company, Kiefer was a great location because it was on the St. Louis & San Francisco Railway (the “Frisco” line) connecting the Glenn Pool to Tulsa.

The notoriety of Kiefer’s oil boom rivaled that of Pithole, Pennsylvania, after the Civil War, and the giant oilfield discovery at Spindletop, Texas, in 1901.

“There was a two or three story building on the creek, just east of the railroad in Kiefer, where the workers could get a shave and haircut, get a bath, get a meal, get the service of a prostitute, get drunk, gamble, and get rolled without ever leaving the building,” a Mounds Enterprise reporter claimed.

“It was not uncommon to find the dead body of one of these oil field workers in the creek, floating in the waist-deep oil,” the newspaper added. Shotgun-toting guards were hired to protect the Ida Glenn No. 1 oilfield discovery well.

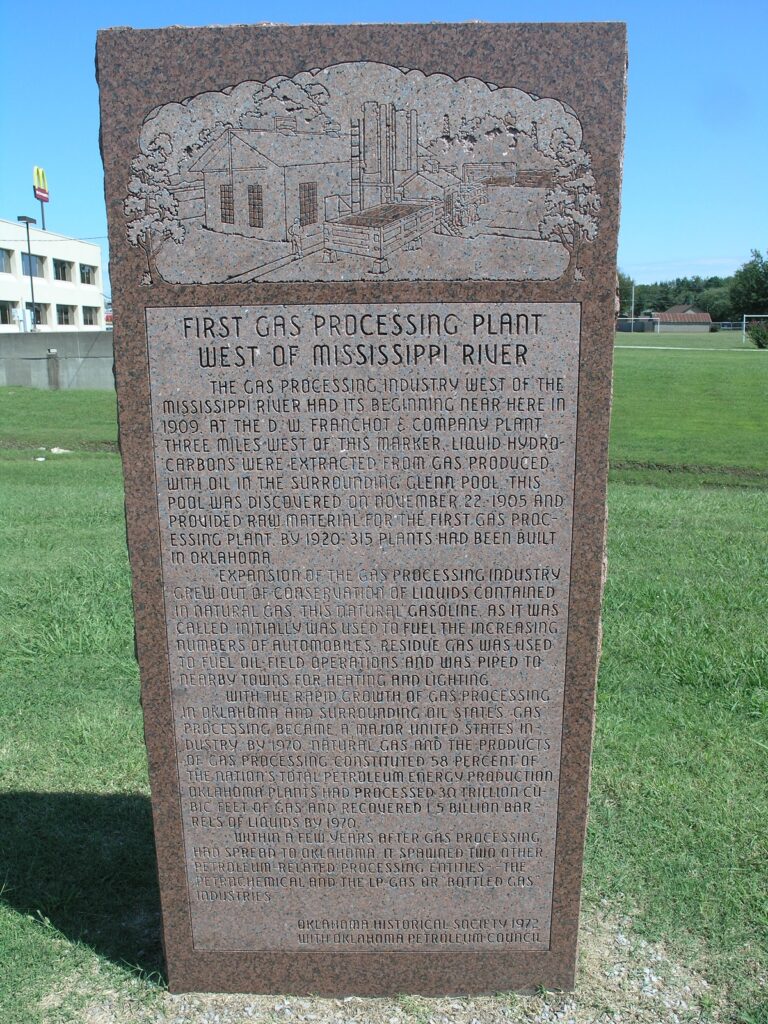

The D.W. Franchot & Company casinghead gas plant was the first to be built west of the Mississippi River. Despite Kiefer’s reputation, investment potential brought numerous ventures.

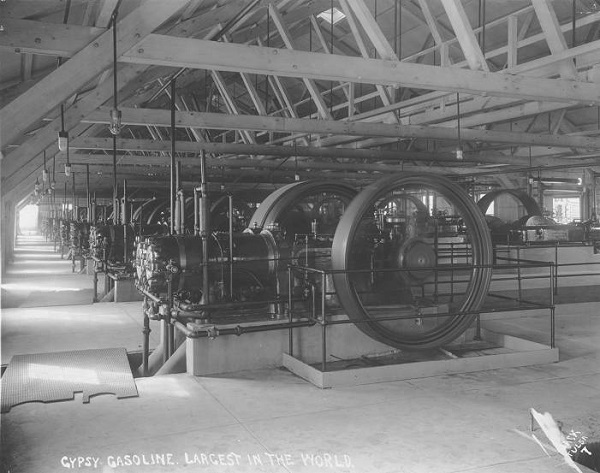

The booming town soon hosted Quaker Oil, Crosby & Gillespie, Chestnut & Smith, McJunkin & Company, Prairie Oil & Gas, the Glenn Gas Company, and the Gypsy Oil Company, which would boast its Kiefer casinghead gasoline plant as the “largest in the world.”

Among the many new oilfield ventures attracted to Kiefer and the Glenn Pool, the Gypsy Oil Company boasted its casinghead gasoline plant was the world’s largest.

According to the Oklahoma Historical Society (OHS), by 1920 there were 315 casinghead plants in the state. A marker in Kiefer notes that in its heyday, the town was larger than Tulsa and home to 22,000 citizens, seven banks, three theaters, two lumber yards, an opera house, 16 barber shops, and numerous entertainment houses.

However, as the OHS also has noted of the Glenn Pool, “Flush production between 1906 and 1908 ranged from eighteen to twenty million barrels per year before gas depletion, caused by massive venting, decreased the gas pressure.”

Glenn Pool’s decline would take Kiefer with it, and as the Great Depression began, the town’s population dropped to 600. After half a century of operation, Kiefer’s last casinghead gas company, Warren Petroleum, closed in 1974. About 2,000 people lived in the former boom town in 2020.

In 1972, a granite historic marker, “First Gas Processing Plant West of Mississippi River,” was erected near Kiefer. It noted, “After gas processing had spread to Oklahoma, it spawned two other petroleum-related processing entities. The petrochemical and the LP gas or bottled gas industries.”

“The gas processing industry west of the Mississippi River had its beginning near here in 1909 at the D.W. Franchot & Company Plant three miles west of this marker,” notes a Glenpool marker erected in 1972 by the Oklahoma Historical Society with the Oklahoma Petroleum Council.

The early hazards of casinghead gas were exposed by fatal disasters, including a 1915 explosion in downtown Ardmore, Oklahoma, and the tragic 1937 New London school explosion in Texas, which ended the widespread use of condensate gasoline. Venting and flaring of oilfield well gas would continue.

Venting and Flaring

A lack of gathering line infrastructure at the Glenn Pool oilfield necessitated gas venting and flaring, but environmental concerns and the loss of potential tax revenues prompted state lawmakers to intervene. All of the 33 producing states have adopted regulations to limit or prevent the waste of gas resources.

However, flaring limits and other regulations have varied from state to state — and casinghead gas has remained a principal offender. Drilling technologies, designed for safety and environmental protection, now include step-flaring and other innovations, where surging gases can be processed, stripped of useful products, and reduced to carbon dioxide and water vapor.

As with the Glenn Pool boom 100 years earlier, associated gas production from modern wells must be carefully managed, especially in the Permian Basin in Texas and the Bakken Formation in North Dakota. By 2017, both states vented or flared gas volumes up to 20 times those reported by the other states.

Oil and natural gas operations remain the largest industrial source of U.S. methane emissions, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which in December 2023 issued a final rule with procedures for states to reduce emissions — including, for the first time, from existing sources nationwide.

Economically viable alternatives to venting and flaring include new technologies that use compressed natural gas systems and modular, remotely operated mini-gas-to-liquid plants. Other methods feature staged flaring, smokeless combustion, and sensor methane surveillance.

Further, modular electricity generation and truck-mounted liquefied natural gas plants have become more practical, according to the World Bank, which has noted, “Remotely operated mini-gas-to-liquid plants may often, in the right circumstances, be economically viable alternatives to flaring.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Petroleum Geology In Oklahoma (2013); Tulsa Oil Capital of the World, Images of America

(2004); Tulsa Where the Streets Were Paved With Gold – Images of America

(2000). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Casing Head Gasoline at Glenn Pool.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: aoghs.org/products/casing-head-gasoline-at-glenn-pool. Last Updated: September 22, 2025.Original Published Date: March 30, 2023.