Post-Civil War oilfields launched Allegheny petroleum boom.

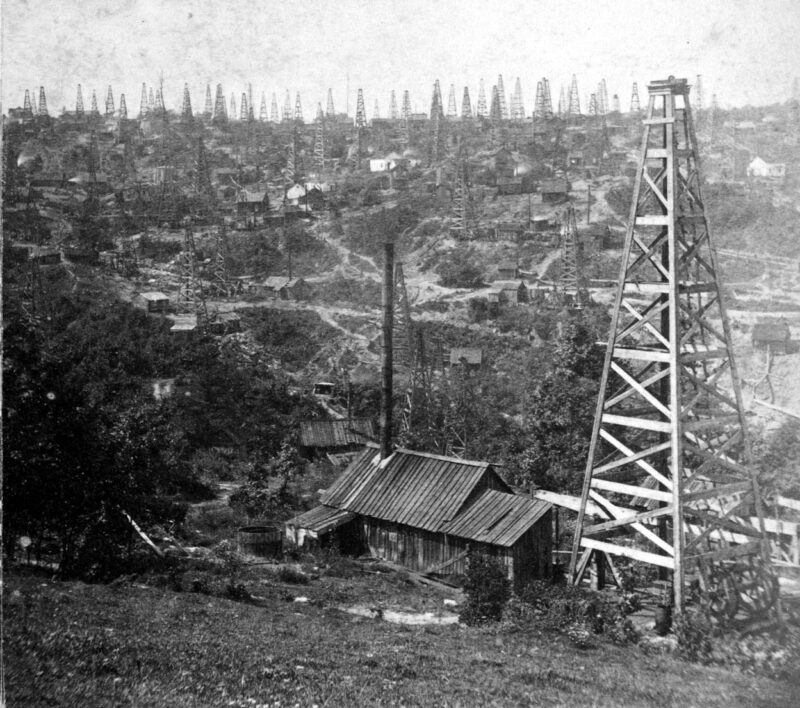

Soon after the Civil War ended and demand for kerosene lamp fuel soared, the rapidly growing U.S. petroleum industry discovered oilfields west of Tidioute, Pennsylvania. Wooden derricks replaced trees on Triumph Hill.

Formerly quiet Pennsylvania hillsides of hemlock woods vanished in early October 1866 when oil fever came to Triumph Hill. The U.S. oil industry was barely seven years old. About 15 miles east of the 1859 first American oil well at Titusville, an 1866 oil discovery at Triumph Hill sparked a rush of uncontrolled development.

An 1870s photograph of the east side of Triumph Hill, near Tidioute, Pennsylvania, by Frank Robbins of Oil City. Image is right half of a stereo card rendered black and white for clarity from original sepia tone. Photo courtesy Biblioteca Nacional Digital Brazil.

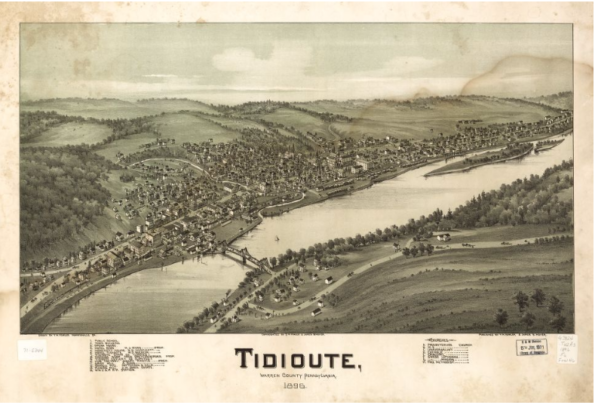

The oil drilling craze would not last long, but boom towns sprang up at Gordon Run and Daniels Run west of Tidioute on Pennsylvania’s Allegheny River.

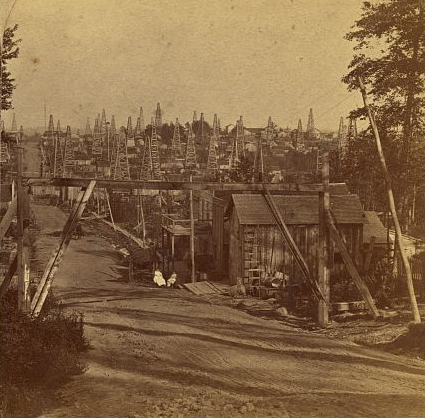

Like the earlier discoveries at Titusville, Rouseville, and Pithole, hillside trees were turned into derricks and oil storage tanks as drilling intensified. News about a deadly Rouseville oil well fire in April 1861 had been overshadowed by the Civil War.

The excitement at Tidioute (pronounced tiddy-oot) was joined by the roughneck-filled towns of Triumph and Babylon, where “sports, strumpets and plug-uglies, who stole, gambled, caroused and did their best to break all the commandments at once.”

Fresh from the oilfields at booming Pithole 25 miles to the southwest, the infamous Ben Hogan, self-proclaimed “Wickedest Man in the World,” operated a bawdy house on the Triumph hillside along the Allegheny River.

Latest Pennsylvania Oil Boom

Despite growing recognition that crowded drilling reduced reservoir pressures and production, the exploration and production bonanza, which began with the first well on October 4, 1866, prompted a frenzy of drilling as investors tried to cash in before the oil ran out.

Detail from a Frank Robbins stereographic view of the west side of Triumph Hill, “showing buildings, storage tanks, and derricks, as well as two children sitting in chairs outside a building on Triumph Hill, near Tidioute, Pennsylvania,” — Library of Congress.

By the summer of 1867, Triumph Hill was producing 2,000 barrels of oil a day. The flood of oil bought lower prices — an early example of the petroleum industry’s boom and bust cycles.

Photographer Frank Robbins of Oil City published stereographic images of Triumph Hill, declaring it to be “the most magnificent oil belt (as oil men call a strip of producing land) ever yet discovered.”

He added, “On this belt which is but two miles long, and less than one mile wide — were over 180 producing wells, nearly every one of which was in operation at once.”

Robbins, who moved his studio to Bradford in 1879 when that region was on its way to becoming “America’s first billion-dollar oilfield,” also printed postcards for sale to tourists.

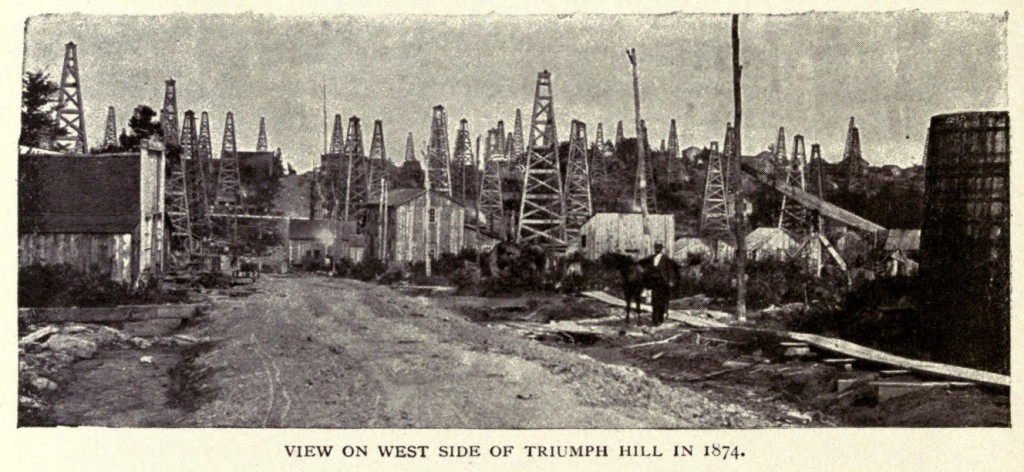

An image from the 1903 edition of “Sketches in Crude-Oil; some accidents and incidents of the petroleum development in all parts of the globe” by James McLaurin.

“Triumph Hill turned out as much money to the acre as any spot in Oildom,” noted James McLaurin in his 1896 book Sketches in Crude-Oil (some accidents and incidents of the petroleum development in all parts of the globe).

Many of the hill’s wells averaged 25 barrels of oil a day, McLaurin reported, adding that “the sand was the thickest – often ninety to one hundred and ten feet – and the purest the oil region afforded.” The tempo of oil exploration around Tidioute and boom town debauchery slowed as the region’s daily production fell.

Drilling discipline and well spacing, reservoir engineering and other oilfield management skills would evolve, but Triumph Hill’s glory dissipated within five years as overproduction drained the field.

Today, Triumph Hill remains one of the many quietly beautiful and forest-covered sites along the Allegheny River Valley that has earned a special place in America’s petroleum history.

Tidioute also is among the earliest panoramic maps of America’s petroleum communities. The view was created by Thaddeus Mortimer Fowler, a popular “bird’s-eye view” cartographer. Learn more about Fowler and his maps in Oil Town “Aero Views.”

Traveling from Pennsylvania to Texas at the turn of the century, Thaddeus Mortimer Fowler created oil town “aero views” – panoramic maps of many of America’s earliest petroleum communities. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Early Oilfield Photography

Pioneer petroleum industry photographers like “Oil Creek Artist” John A. Mather documented Northwestern Pennsylvania boom towns. He and others like Frank Robbins captured views of North American oil booms, according to geologist and historian Jeff Spencer, noting, “Common scenes included oil gushers, oilfield fires, teamsters, and boom towns.”

Frank Robbins documented the emerging 1860s Pennsylvania petroleum industry, Spencer noted in a 2011 article for the journal Oil-Industry History. “He was one of the most prolific producers of stereoscopic views of oilfields in the Oil City and Bradford, Pennsylvania, and Olean, New York area,” Spencer noted.

Stereoscopic view by Frank Robbins: “Drake Well, the first oil well.” Courtesy New York Public Library.

Robbins photographed scenes from oilfields at Triumph Hill, Tidioute, Petrolia, and Pithole, according to Spencer, who in 2003, published Texas Oil and Gas (Postcard History Series) — learn more in Postcards from the Texas Oil Patch. For more resources on oilfield images, see petroleum photography websites.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Cherry Run Valley: Plumer, Pithole, and Oil City, Pennsylvania, Images of America (2000); Around Titusville, Pa., Images of America

(2004); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Derricks of Triumph Hill.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/triumph-hill-oil. Last Updated: September 26, 2024. Original Published Date: July 3, 2015.