After months of hard drilling, a North Texas oil well roared in at Ranger in 1917.

As World War I continued in Europe, the “Roaring Ranger” oilfield discovery well of October 1917 in Eastland County, Texas, revealed a giant oilfield that would help fuel the Allied victory.

Residents of the town of Ranger — about halfway between Dallas and Abilene — had been eager to find oil, especially after reading newspaper accounts of an oilfield discovery on April Fool’s Day 1911 at Electra in neighboring Wichita County. A decade earlier in southeastern Texas, the “Lucas Gusher” at Spindletop Hill had launched the modern U.S. petroleum industry.

Detail of a photo showing “Roaring Ranger,” the McCleskey No. 1 well, erupting oil in Eastland County and launching a North Texas drilling boom. Photo courtesy Ranger Historical Preservation Society.

As the area’s cotton farmers struggled with severe drought, Ranger town officials hoped to strike “black gold.” For help, they turned to William K. Gordon, vice president of the Texas and Pacific Coal Company in Thurber. His company mined shale from hills near Thurber.

“Roaring Ranger”

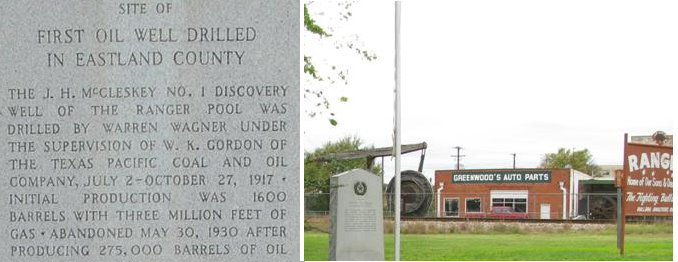

After one failed test with a shallow well, Gordon agreed to drill the second attempt up to 3,500 feet deep. Drilling with basic cable-tool technology, Gordon and contractor Warren Wagner spudded the exploratory wildcat well on July 2, 1917, on the McCleskey farm, two miles south of Ranger.

After more than three months of drilling, the J.H. McCleskey No. 1 well erupted a geyser of oil on October 17, 1917, from a depth of 3,432 feet.

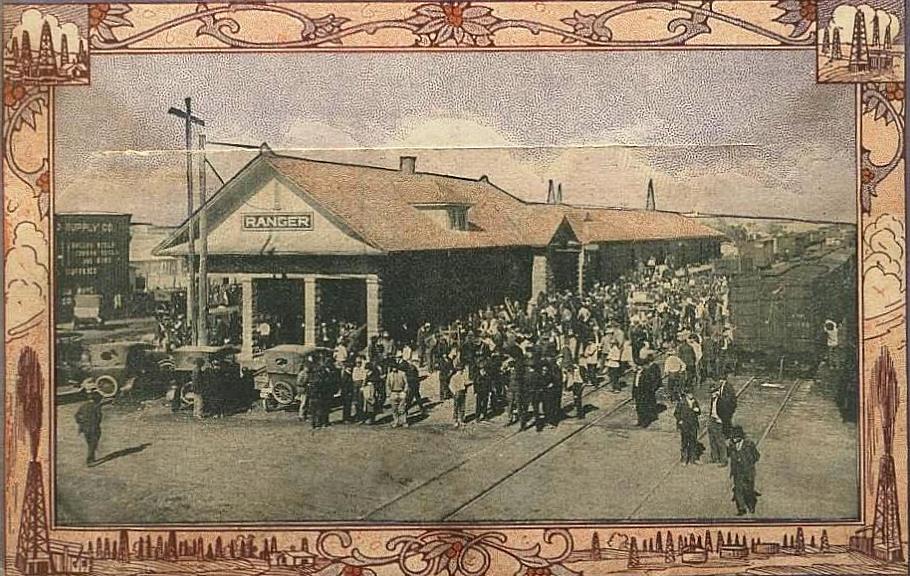

Following the October 1917 oilfield discovery, the Texas and Pacific Railroad transported people, equipment, and petroleum in and out of Ranger. A circa 1920 postcard shows the depot, future home of the Roaring Ranger Oil Boom Museum.

When completed, “Roaring Ranger” initially produced 1,600 barrels of high-gravity oil per day. Later oil gushers yielded up to 10,000 barrels of oil daily. Within 20 months, Texas and Pacific Coal Company stock jumped from $30 a share to $1,250 a share.

The suddenly wealthy petroleum exploration company added “oil” to its name, reorganizing as the Texas Pacific Coal and Oil Company.

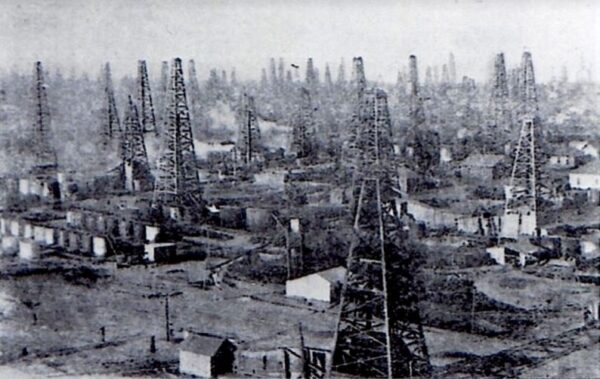

“Almost overnight, you couldn’t even see the homes for the derricks,” said Ranger historian Jeane B. Pruett. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

Eastland County oil discoveries brought economic booms to Ranger, Cisco, and Desdemona — today a ghost town. As leasing intensified in and around Desdemona by 1918, convincing the congregation of a Baptist Church to allow drilling proved to be a challenge (see Oil Riches of Merriman Baptist Church).

Among the veterans visiting booming Eastland County after the war was a young Conrad Hilton, who visited Cisco intending to buy a bank. When he witnessed the long line of roughnecks waiting for a room at the Mobley Hotel, he decided to buy the hotel (see Oil Boom Brings First Hilton Hotel).

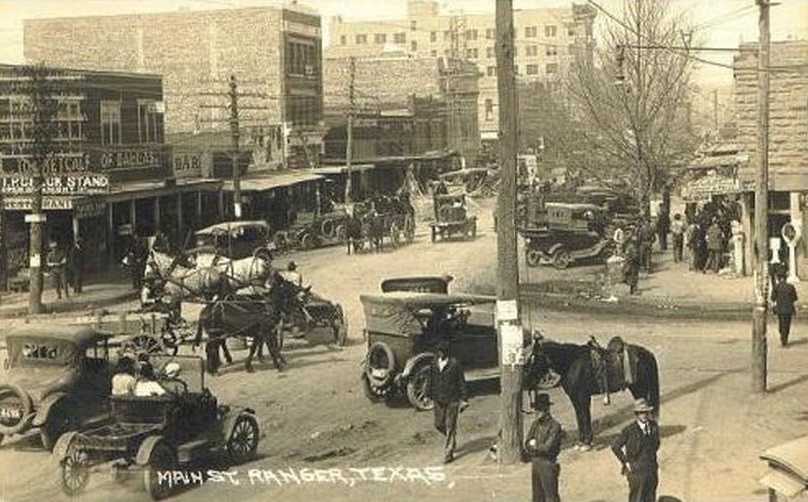

The Abilene Reporter-News reported Ranger’s population swelled from less than 1,000 to more than 30,000 — mostly men. Opportunities for illicit financial gain also attracted notorious oilfield hucksters like J.W. “Hog Creek” Carruth (see Exploiting North Texas Oil Fever).

The 2016 Roaring Ranger Day Parade took place on the 99th birthday of the town’s famous oil gusher. Photo courtesy Ranger Historical Preservation Society.

Eastland County’s drilling and production boom grew rapidly as petroleum companies rushed to Ranger to develop the giant oilfield, according to historian Damon Sasser.

By 1919, the Texas Pacific Coal and Oil Company had 22 oil wells — and eight refineries open or under construction. More freight was unloaded in Ranger by the railroad than at any other place upon its line, including stations in Fort Worth, Dallas and New Orleans.

The J.H. McCleskey No. 1 discovery well of October 1917 created a mammoth oil boom at Ranger and across Eastland County, Texas. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

The flood of people also brought Texas Rangers to the boom town, which had begun as a Ranger camp in the 1870s. When Ranger jails overflowed, the lawmen handcuffed prisoners to telephone poles.

Meanwhile, independent and major exploration companies discovered nearby oilfields, including the Parsons, Sinclair-Earnest, and Lake Sand fields.

Photos courtesy Sarah Reveley and Barclay Gibson, who have photographed Texas Historical Commission markers and helped locate hundreds of historic sites from Louisiana to New Mexico.

Production from the Breckenridge oilfield in neighboring Stephens County was 10 million barrels of oil by 1919. It peaked at more than 31 million barrels of oil in 1921.

“Wave of Oil” wins WW I

“Roaring Ranger” and the region’s production had proved essential to the Allied victory in World War I. When the armistice was signed in 1918, a member of the British War Cabinet declared, “The Allied cause floated to victory upon a wave of oil.”

Ranger’s boom ended in the early 1920s when excess oil production caused wells to fail, but the discoveries confirmed the existence of a large petroleum-producing region, the Mid-Continent, with hundreds of oilfields stretching from Texas into Oklahoma and Kansas.

Eastland County oil discoveries, which began with the “Roaring Ranger” well of 1917, brought economic booms to Ranger, Cisco, and Desdemona. Photo courtesy Jeane B. Pruett and the family of W.K. Gordon Jr.

Established by the Ranger chamber of commerce in 1982, the Roaring Ranger Oil Boom Museum — inside the original Texas and Pacific Railway’s depot — exhibits drilling equipment, historic photos and a vintage cable-tool rig.

Ranger residents annually celebrate their 1917 oilfield discovery with a festival and parade down Main Street. When the parade crosses the historic train depot’s tracks, participants pass a small, gray granite marker dedicated to the “First Oil Well Drilled in Eastland County.”

The 1936 Texas Centennial marker remains “a highly cherished monument that Ranger should be very proud of,” according to Eastland County resident Sarah Reveley, who documented many Texas Historical Commission sites.

Other dedicated advocates for preserving local petroleum history included Jeane B. Pruett (1935-2022), a longtime friend of the American Oil & Gas Historical Society.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Ranger, Images of America (2010); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power

(2008); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Roaring Ranger wins WWI.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/roaring-ranger-wins-wwi. Last Updated: October 10, 2025. Original Published Date: July 1, 2004.