Oil discovery on widow’s East Texas farm confirmed the size of largest oilfield in the lower 48 states.

Some people claimed a gypsy told Malcolm Crim he would discover oil in East Texas three days after Christmas. Others said it was because his mother, Lou Della “Mama” Crim, was a pious woman.

On December 28, 1930, the exploratory well Lou Della Crim No. 1 began producing an astonishing 20,000 barrels of oil a day. Even then, few appreciated the true significance of the Rusk County well drilled by Mrs. Crim’s eldest son, Malcolm.

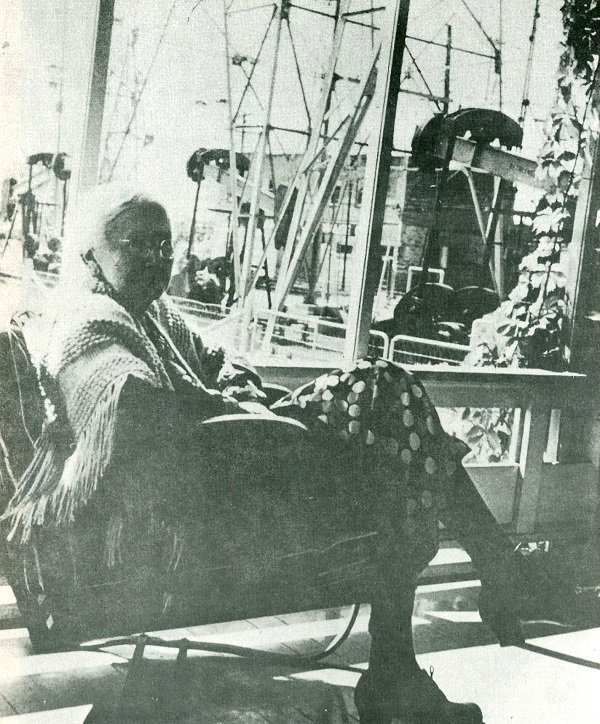

“Mrs. Lou Della Crim sits on the porch of her house and contemplates the three producing wells in her front yard,” notes the caption of this undated photograph about the wells that followed the historic 1930 discovery on her farm. Image courtesy Caleb Pirtle and Neal Campbell, Words and Pictures.

The region’s latest oil discovery brought headlines in Dallas newspapers, especially since Mrs. Crim’s well was about nine miles north of an earlier oil gusher on another widow’s farm. Everyone at first thought a second East Texas oilfield had been found.

In October, the Daisy Bradford No. 3 well of Columbus “Dad” Joiner had disproved experts who claimed East Texas contained no oil. Yet the distance between these discoveries convinced geologists — and major petroleum exploration companies — that the wells had found separate oilfields.

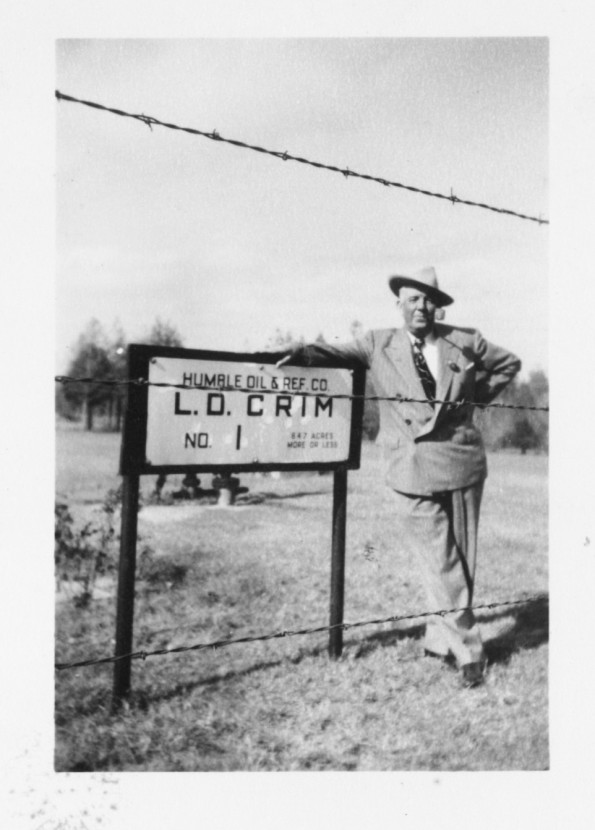

Malcolm Crim stands at site of his famous 1930 East Texas oil well, the Lou Della Crim No. 1, named after his mother.

No one was aware that the two “wildcat” exploratory wells were part of what was a geological phenomenon, according to historian and oil museum founder Joe White of Kilgore.

“An incredible deposit of oil in the Woodbine formation had ‘pinched out’ as it tilted upward against the Sabine Uplift, creating the massive East Texas oilfield,” White explained in 2004. The two wells launched a drilling frenzy remarkable even for Texas, home of the 1901 “Lucas Gusher” at Spindletop Hill and “Roaring Ranger” oilfield of 1917.

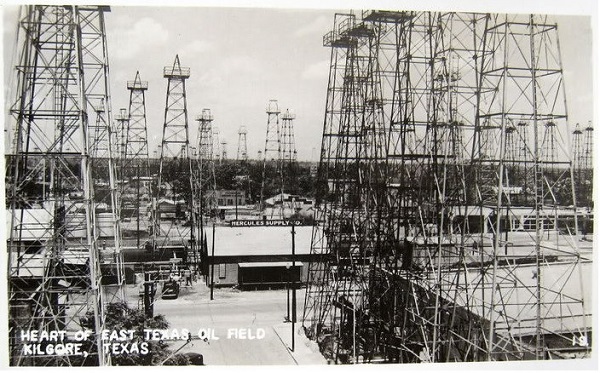

Surrounded by cotton farms in the grip of a devastating drought, Kilgore’s population grew from 700 to 10,000 in just a few days after the discovery, according to White, who founded the East Texas Oil Museum in 1980, the 50th anniversary of the Daisy Bradford well.

A Geologic Wonder

Like “Dad” Joiner, Malcolm Crim had ignored reports from geologists who claimed, in good conscience, that the earth below Kilgore was barren and worthless, explained author Caleb Pirtle III in 2011. “The drought-stricken soil grew a few vegetables for families to eat but little else.”

Discovered in 1930, the East Texas oilfield brought great wealth to Kilgore and other small towns. The field’s massive production gave the Allies the petroleum reserves needed to help win World War II.

But Malcolm Crim was not a farmer. “He owned a little mercantile store downtown, peddling, he once said, everything from candy to coffins,” Pirtle noted. As the end of the 1920s approached, Crim’s business cash drawer “was filled with a few coins and greenbacks, but mostly IOUs.”

A fifty-cent fortune from a gypsy had given Crim a psychic glimpse of the land under his mother’s farm “turning black with oil,” explained Pirtle, who has written more than 55 books (see Amazon bio), including three about the East Texas oilfield: Echoes from Forgotten Streets, Visions of Forgotten Streets, and Life on Kilgore’s Unforgettable Streets.

The psychic gypsy seemed to know a lot about Malcolm Crim’s past, so “there was no reason for him to doubt that she had a clear view of his future as well,” Pirtle added.

The East Texas oilfield remains the largest and most prolific oil reservoir ever discovered in the contiguous United States.

Crim obtained scattered leases, including some on the farm of his mother. He needed a petroleum company with a skilled driller — but no company wanted to risk an expensive exploratory well on a gypsy’s vision, Pirtle said. They knew of the many “dusters” drilled by “Dad” Joiner in the late 1920s.

“No one had watched the exasperating failures of Dad Joiner’s poor boy venture with more interest than Malcolm Crim,” Pirtle noted. “Even while the old wildcatter was preparing to drill Daisy Bradford No. 3, Crim was meeting in Kilgore with two employees of a little independent Fort Worth oil company operated by Ed Bateman.”

Bateman, a former newspaperman with the Dallas Times Herald, became intrigued with the promise of oil in East Texas, according to Pirtle. While searching for leases, Bateman had met a driller named Elmer Hays, who promised to help him find a lease “if you’ll let me drill the well.”

Hays introduced Bateman to Crim, because it was time that “two good men with the same dream finally got together.”

Crim was not a difficult man to find, according to Pirtle, who also wrote The Man Who Believed in Fortune Tellers. He cited Hays’ sister saying, “You just pick out the man in the raggedest britches and the slouchiest hat.”

The fortunes of Kilgore’s mercantile store owner changed forever on December 28, 1930 – as did those of many who lived on the 140,000 acres in five counties above the East Texas oilfield.

No sooner had the oil wells come in than Malcolm Crim, owner-operator of his family’s local general store, with whom everyone in town did business, declared that all debts were forgiven. Crim invited his customers down to the store where he tore up their IOU papers into scraps and burned them saying “we’re wiping the slate clean, we’re even with everybody.”

He knew what conditions were like for his fellow citizens and he knew immediately how the discovery of oil would change all of their situations for the better. It was also an early example of the many similar charitable acts for the good of the community that the Crims performed in the following years. — From Neal Campbell, Words and Pictures.

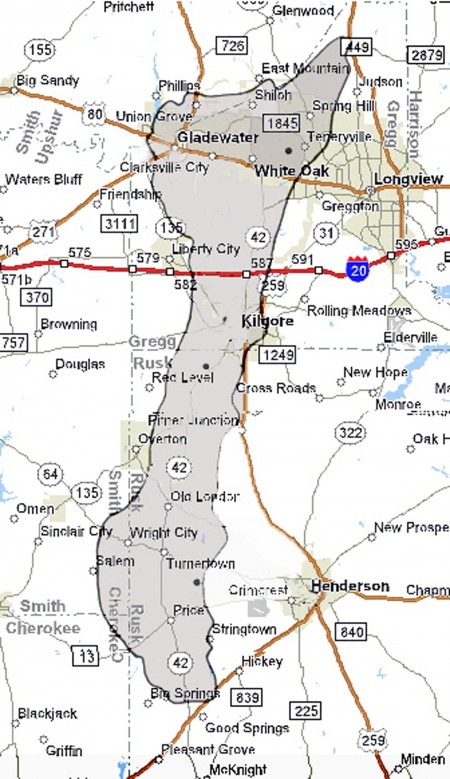

In January 1931 a third well proved the East Texas oilfield was the largest ever when Fort Worth wildcatter W.A. “Monty” Moncrief drilled the J.K. Lathrop well on a lease in Gregg County (see Moncrief makes East Texas History). This historic well produced 18,000 barrels of oil a day, 15 miles north of the Lou Della Crim No. 1.

During World War II, the need to get oil to East Coast refineries led to the construction of special pipelines (see Big Inch Pipelines of WW II).

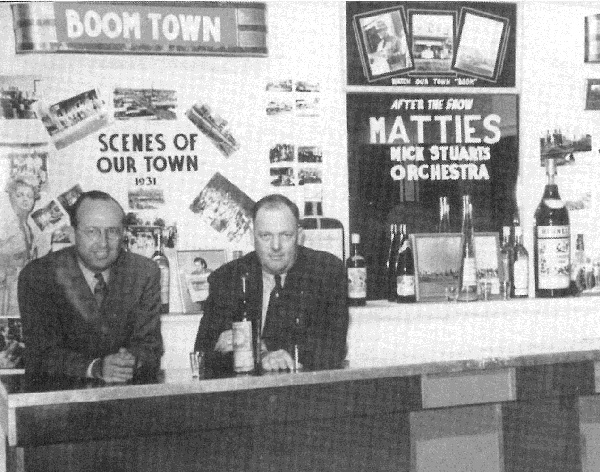

“The two men who gave Kilgore entertainment and fireworks, Liggett Crim, left, and Knox Lamb, prepare for the opening of Boom Town, starring Clark Gable and Spencer Tracy. The movie revived memories of Kilgore’s own boom, featured with old photographs on the counter.” Caption of undated photograph. Image courtesy Neal Campbell, Words and Pictures.

The East Texas oilfield — which proved to be 43 miles long and 12.5 miles wide — produced more than five billion barrels of oil by the end of the 20th century. Aided by improved reservoir management technologies, the oil production from the Black Giant continues.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Black Giant: A History of the East Texas Oil Field and Oil Industry Skullduggery & Trivia (2003); Texas Rich: The Hunt Dynasty (1982); Historic Photos of Texas Oil

(2012); Texas Oil and Gas, Postcard History

(2013). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Lou Della Crim Revealed.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/lou-della-crim-revealed. Last Updated: December 19, 2025. Original Published Date: April 29, 2013.