Thousands of glass-negative images document the earliest scenes of America’s petroleum industry.

Soon after the first American oil well in 1859 launched the U.S. petroleum industry in remote northwestern Pennsylvania, an English emigrant began documenting life in the oilfields.

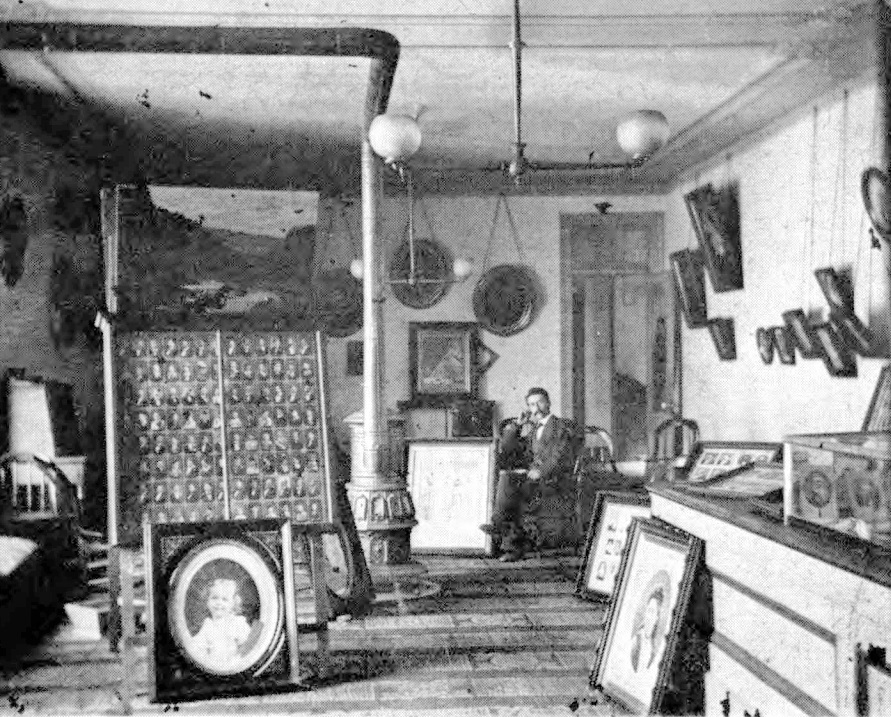

John A. Mather (1829-1915) photographed the people, places and technology from the earliest days of oil exploration. In the fall of 1860, he set up his first studio in Titusville, Pennsylvania — where he would begin to amass more than 20,000 glass-plate negatives.

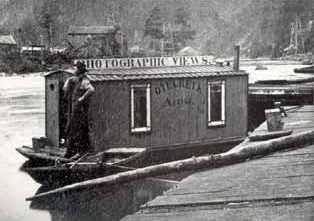

Oil Creek Artist

Titusville and nearby Oil City and Franklin, in the heart of the growing Pennsylvania oil regions (soon joined by the boom town of Pithole), proved ideal locations for documenting the people, events and evolving drilling technologies of petroleum exploration and production.

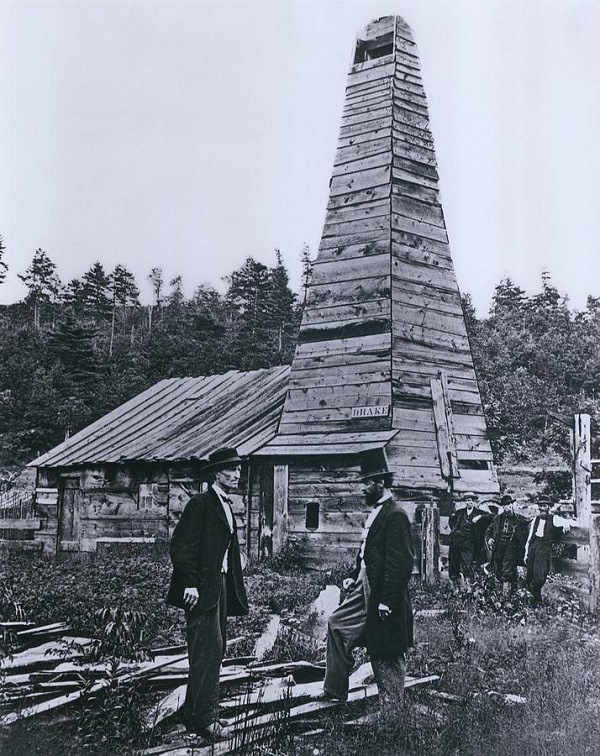

Iconic but often misidentified 1866 photo by John A. Mather features Edwin L. Drake (in top hat) with friend Peter Wilson standing at the rebuilt derrick and engine house of the 1859 first U.S. commercial oil well. Photo courtesy Drake Well Museum and Park.

What Civil War photographers Matthew Brady and James Gardner documented on battlefields, Mather accomplished in Pennsylvania’s oilfields. In 1866, Titusville’s “Oil Creek Artist” photographed the now iconic image of Edwin L. Drake, standing at the original drilling site (rebuilt after the first oil well fire).

Like Brady, Mather abandoned making one-of-kind daguerreotypes and ambrotypes in favor of wet plate negatives using collodion — a flammable, syrupy mixture also called “nitrocellulose.” With one glass plate, many paper copies of an image could be printed and sold.

However, unlike most of the era’s studio photographers, Mather transported his camera and chemicals into the industrial chaos of early Pennsylvania oilfields. But like most people in the new oil region, Mather was susceptible to “oil fever;” he hoped to drill some successful wells himself.

Oil Fever

Above all, the oil regions continued to boom. The gamble of drilling for new oilfield discoveries brought excitement. As “oil fever” spread, polka and waltz song sheets like the Petroleum Court Dance became popular.

Having narrowly missed the opportunity for a one-sixteenth share of the Sherman Well, which proved to be the “best single strike of the year,” Mather and three associates invested in oil wells near booming Pithole Creek. He proved to be better at using a camera.

John Mather photographs courtesy Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine and Drake Well Museum, Titusville. Above, the interior of his Titusville studio, circa 1865.

Mather’s investment in finding oil at Pithole Creek did not lead to producing any commercial quantities. He tried again on the Holmden Farm off West Pithole Creek. His unsuccessful drilling effort proved to be one of the last wells in the infamous boom town Pithole.

Many tried, but few in the increasingly crowded oil regions would rival the wealth of the celebrated “Coal Oil Johnny.” Years later, Mather acknowledged that the excitement of the drilling for “black gold” was so great that he “forsook photography for the oil business.”

Meanwhile, the young U.S. petroleum industry learned some hard lessons. Highly pressurized wells and disasters like the 1861 fatal Rouseville oil well fire brought attention to a new science, petroleum geology.

Detail from the 19th-century stereoview “Oil Regions of Pennsylvania,” published by C. W. Woodward of Rochester, N.Y., featuring John Mather’s floating studio and dark room.

Returning to the oilfields with his camera, Mather’s rolling darkroom and floating studio traveled up and down Oil Creek. In 2008, photographic historian John Craig (1943-2011) noted the discovery of a Mather image in a stereoview card published by C.W. Woodward.

“We have had the card for years and assumed that the boat belonged to Woodward,” the historian noted. “When I made the scan I noticed that the side of the boat carried a sign ‘Oil Creek Artist.’ I Googled and found that the studio/darkroom boat belonged to John A. Mather.”

At its peak, Mather’s collection amounted to more than 16,000 glass negatives. The trade magazine Petroleum Age described his oilfield photography as “so perfect in finish it stands the test of time.”

Oil Creek Flood and Fire

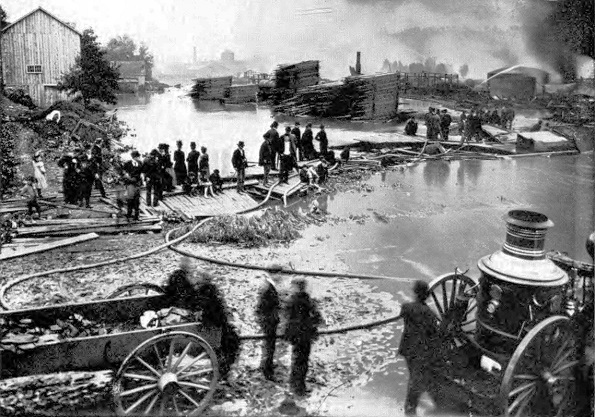

On Sunday morning June 5, 1892, and after weeks of rain, Oil Creek’s overflowing Spartansburg Dam failed at about 2:30 a.m. A wall of water and debris swelled towards Titusville and its oil works, seven miles downstream.

“On rushed the mad waters, tearing away bridge after bridge, carrying away horses, homes and people,” one newspaper reported about the flood’s devastation. Then fire erupted from ruptured benzine and oil storage tanks.

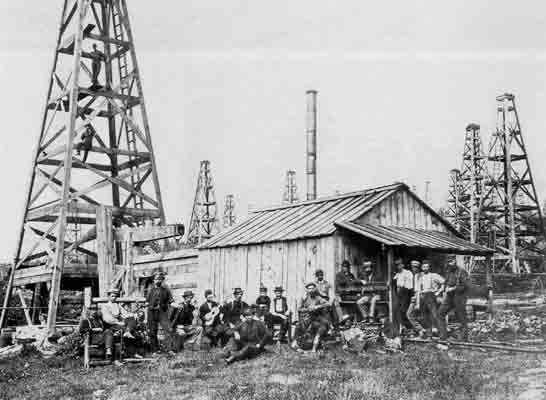

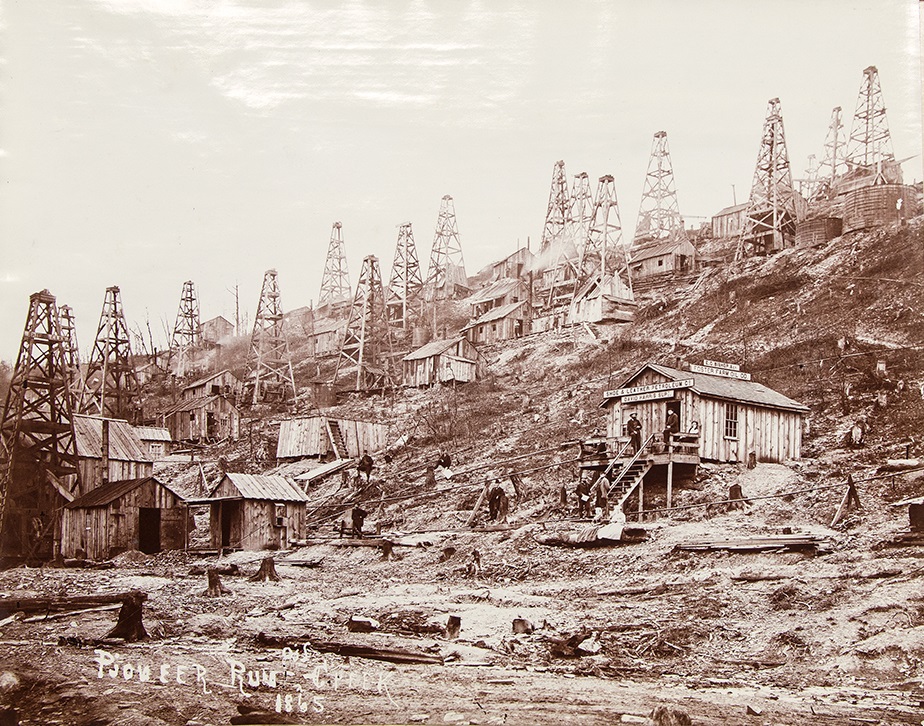

Oilfield workers pose on and among their oil derricks and engine houses in this 1864 John Mather photo from the Drake Well Museum collection in Titusville, Pennsylvania.

Newspapers all over America carried stories of the disaster. In Montana, the Helena Independent headlines included: “Waters of an Overflowing Creek Become a Rushing Mass of Flames” and victims being, “Spared by the Deluge Only to Become the Prey of the Fire.”

John Mather’s photographs documented family life in remote early oil boom towns. He also briefly caught “oil fever” and unsuccessfully invested in a few wells in the booming Pithole Creek field.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle added: “The Waters Subside and The Flames Die Away, Revealing the Full Extent of the Calamity.” Oil City and Titusville were “Nearly Wiped From Off the Earth.”

Unfortunately, Mather’s studio flooded to a depth of five feet, destroying expensive equipment — and most of his life’s work of prints from glass plate negatives.

Pennsylvania oil towns were “Nearly Wiped From Off the Earth” by an 1892 fire and flood that destroyed thousands of Mather’s prints and glass plates. Photo from Drake Well Museum collection.

As the fires and flood continued, Mather set up his camera and photographed the disaster in progress with his bulky equipment, which already was being rendered obsolete by new imaging technologies.

Photography Legacy

Just a few years before the Titusville flood, George Eastman of Rochester, New York, introduced celluloid roll film and created an entirely new market: amateur snapshot photography.

Expertise in preparing fragile glass plates and dangerous chemicals was no longer required. Instead, Kodak offered, “You Press the Button, We Do the Rest.”

The “Oil Creek Artist” visited potential customers using his floating darkroom.

As oil booms moved to discoveries in other states, including the massive 1901 “Lucas Gusher” in Texas, Mather worked little in his later years. His financial circumstances diminished with age and illness.

The Artist of Oil Creek died poor and without fanfare on August 23, 1915, in Titusville. His death certificate reported the cause as cerebral hemorrhage, “complicated by suppression of urine.”

An 1865 John Mather photograph of wooden derricks, engine houses, oilfield workers, an office (and tree stumps) at Pioneer Run – Oil Creek, Pennsylvania.

To preserve John A. Mather’s petroleum industry legacy, the Drake Well Memorial Association purchased 3,274 surviving glass negatives for about 30 cents each.

The Drake Well Museum has preserved the photographer’s surviving work. The museum and surrounding park allow visitors to explore rare artifacts and a visual record of the early U.S. oil and natural industry. Visit the Titusville museum along Oil Creek and other Pennsylvania petroleum museums.

More Resources

“Virtually unknown, certainly unheralded, and completely unappreciated — in these few words is a description of John Aked Mather, pioneer photographer, ” proclaimed Ernest C. Miller and T.K. Stratton in their January 1972 article, “Oildon’s Photographic Historian,” in The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine (Volume 55, Number 1).

Born in Heapford Bury, England, in 1829, the son of an English papermill superintendent, Mather joined his two brothers in America in 1856. He soon became “transfixed by the beauty of the Pennsylvania and Eastern Ohio regions,” explains a NWPaHeritage article, adding he developed an “obsessive desire to capture the industry in its entirety.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Western Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage (2008); Around Titusville, Pa., Images of America

(2004); Cherry Run Valley: Plumer, Pithole, and Oil City, Pennsylvania, Images of America (2000); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Oilfield Photographer John Mather.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-art/oilfield-photographer-john-mather. Last Updated: May 30, 2025. Original Published Date: March 11, 2005.