Secret WW II project sent Oklahoma drillers to British oilfield, adding one million barrels of oil production by 1944.

As the United Kingdom fought for its survival during World War II, a team of American oil drillers, derrickhands, roustabouts, and motormen secretly boarded the converted troopship HMS Queen Elizabeth in March 1943. Once their story was revealed years later, they would become known as the Roughnecks of Sherwood Forest.

The 42 volunteers from Noble Drilling and Fain-Porter Drilling companies taken before they secretly embarked for the United Kingdom on March 12, 1943, aboard HMS Queen Elizabeth, which had been converted into a troop transport. Photo courtesy Guy Woodward Collection, American Heritage Center.

By the summer of 1942, the situation was desperate. The future of Great Britain — and the outcome of World War II — depended on the supply of petroleum. At the end of that year, demand for 100-octane fuel had grown to more than 150,000 barrels every day — and German U-boats ruled the Atlantic.

British Secretary of Petroleum, Geoffrey Lloyd in August 1942 called for an emergency meeting of his country’s Oil Control Board to assess the “impending crisis in oil.”

U.S. oil tanker Pennsylvania Sun was torpedoed by U-571 on July, 15, 1942, about 125 miles west of Key West, Florida, at a time when Britain’s oil reserves were 2 million barrels below safety reserves. Photo courtesy of National Museum of the U.S. Navy.

The United Kingdom’s desperate situation would lead to the “little-known, or at least seldom recognized, all-important role oil and oilmen played in the prosecution of the war,” according to two historians who extensively researched war archives there and the United States.

In 1973, Guy Woodward and Grace Steele Woodward published The Secret of Sherwood Forest – Oil Production in England During World War II. “The amazing and hitherto untold story, born in secrecy, has remained buried in the private diaries, corporate files and official records of government agencies,” the Woodwards explained.

“In the final analysis, oil was indeed the key to victory of the Allies over the Axis powers,” the authors concluded.

Dedicated in 2001, an Oil Patch Warrior stands in Ardmore, Oklahoma. The bronze statue is an exact duplicate of one erected 10 years earlier near Nottinghamshire, England. Photos courtesy of the Dukes Wood Oil Museum (closed in 2021).

Two identical bronze statues separated by the Atlantic Ocean commemorate the achievements of American roughnecks. The first seven-foot statue was erected in 1991 near the village of Eakring in Dukes Wood, about 15 miles north of Nottinghamshire, England. A decade later, a twin roughneck statue would greet visitors to Memorial Square in Ardmore, Oklahoma.

Separated by more than 4,605.05 miles (7,411.12 km), the bronze oil patch warriors commemorate Americans who produced oil during a critical time of the war — by drilling in Sherwood Forest.

The Unsinkable Tanker

The once top-secret story begins in August 1942, when Britain’s wartime secretary of petroleum, Geoffrey Lloyd, called an emergency meeting of the country’s Oil Control Board.

U-boat attacks and the bombing of dockside storage facilities had brought the British Admiralty 2 million barrels below its minimum safety reserves. The oil supply outlook was bleak.

A Republic P-47 in Italy is fueled in this February 1945 photograph “passed for publication” by Allied field press censors. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Meanwhile, German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s rampaging North African campaign threatened England’s access to Middle East oilfield sources. England’s principal fuel supplies came by convoy from Trinidad and America and were subjected to relentless Nazi submarine attacks.

Many at the Oil Control Board meeting were surprised to learn England had a productive oilfield of its own, first discovered in 1939 by D’Arcy Exploration. The company was a subsidiary of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, founded in 1908, a predecessor to British Petroleum, BP.

The obscure English oilfield was in Sherwood Forest, at Eakring and Dukes Wood. The field produced modestly from 50 shallow wells.

Noble Drilling Corporation financed a May 1991 trip for 14 survivors of the original crew to return to Duke’s Wood in Sherwood Forest. Photo courtesy of the Dukes Wood Oil Museum.

Extreme shortages of drilling equipment and personnel kept Britain from further exploiting the field. Perhaps America might help. Following the meeting — and under great secrecy — D’Arcy Exploration Managing Director Phillip Southwell was sent to the Petroleum Administration for War (PAW) in Washington, D.C.

Southwell explained that England lacked the equipment and expertise for rapid drilling, even in shallow fields. His secret mission was to secure American assistance for expanding production in the Eakring field, regarded as an “unsinkable tanker.”

“Ninety-four wells produced high quality oil, an amazing achievement,” the BBC would later note. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

According to Jim Day, former CEO of the Noble Corporation, Southwell met with representatives from four oil companies, including Lloyd Noble, president of Noble Drilling, and Frank Porter, president of Fain-Porter Drilling. Officers from the two other companies, California contractors, “quickly bowed out, saying they would not be of any use.”

Noble and Porter remained at the meeting, “speaking at length to Southwell, (who still hadn’t divulged the location of the oil fields), but finally — reluctantly — said they couldn’t help. Porter’s company was too small for the task, and Noble had just committed his resources to the Northwest Territories of Canada.”

Pressing his case, Southwell pursued Noble to the CEO’s hometown of Ardmore to negotiate a deal.

American volunteer derrickhand Herman Douthit fell to his death. Photo detail from American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming.

Noble had purchased his first drilling rig in 1921 while living in Ardmore. Porter, originally from Brooklyn, New York, worked in Ardmore oilfields in 1916 before founding his Oklahoma City drilling company in 1939. Their two companies — like much of the U.S. petroleum industry — were already heavily committed to wartime production.

Ardmore Meeting

Southwell, mindful of England’s desperate situation and doggedly persistent, soon followed Noble to Oklahoma. Arriving in Dallas (the closest major airport to Ardmore), he rented a car and was allocated one tank of tightly rationed gasoline. Southwell made the trip on faith, trusting he would find fuel for the return trip to Dallas.

On September 13, 1942, a Sunday, Southwell arrived at Noble’s home in Ardmore at 10 a.m. Noble answered the door wearing pajamas.

Stirred by patriotic fervor, unable to resist the lure of a challenge or perhaps just impressed by Southwell’s persistence in chasing him across the country, Noble told Southwell that if Porter would join in, Noble Drilling would commit to the venture. Noble would purchase the necessary equipment for D’Arcy and recruit men to run the rigs. Noble surprised Southwell by telling him he wouldn’t expect any profit. The work would be Noble Drilling and Fain-Porter Drilling’s contribution to winning the war.

Noble then convinced Porter to join the mission and Southwell left for Dallas — after the famed oilman secured him a tank of gas.

— from “Oil Field Warriors,” by Jim Day, Noble Research Institute, Winter 2011.

Thanks to D’Arcy Exploration’s Phillip Southwell (later Sir Phillip), Noble Drilling joined with Fain-Porter Drilling on a one-year contract to drill 100 new wells in the Eakring field.

Oklahoma drillers Lloyd Noble (1896-1950) of Ardmore and Frank M. Porter (1892-1962), originally from Brooklyn, N.Y., helped Great Britain produce more than one million barrels of oil. Photo of Noble courtesy Noble Research Institute. Porter photo courtesy Frank P. Stone.

Noble and Porter volunteered to execute the contract for cost and expenses only. PAW approved the Ardmore deal, and a contract was signed in early February 1943.

The English Project: Secret Drilling

On March 12, 1943 a team of 42 newly recruited Noble and Fain-Porter drillers, derrick hands, motor operators, and other roughnecks embarked on the converted troopship HMS Queen Elizabeth.

Four drilling rigs for “The English Project” would be transported to England on four different ships. Although one ship was lost to a German submarine, another rig was subsequently shipped safely.

The Americans stayed at Kelham Hall. Isolated from the community, the Anglican monastery was ideal for the yearlong operation.

The American oilmen joined project managers Eugene Rosser and Don Walker at billets prepared for them in an Anglican monastery at the historic Kelham Hall, near Eakring. The influx of the Americans from Oklahoma was rumored to be for making a movie, probably a Western. It was said that John Wayne would soon arrive.

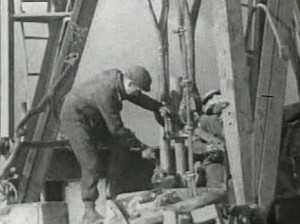

Within a month, sufficient equipment had arrived to enable spudding the first well. Two others quickly followed. Four crews worked 12-hour tours with “National 50” rigs equipped with 87-foot jackknife masts.

When the oilfield workers left to return to America on March 3, 1944, they had added more than 1.2 million barrels of oil to the output of the Eakring oilfield. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The roughnecks amazed their British counterparts with their drilling speed in the field, which had been producing oil from about 7,465 feet since the 1930s.

Using innovative methods, the Americans drilled an average of one well per week in Dukes Wood, while the British took at least five weeks per well. The British crews had made it a practice to change bits at 30-foot intervals. The Americans kept using the same bit as long as it was “making hole.”

By August, the Yanks of Sherwood Forest had completed 36 new wells, despite the challenges of wartime rationing of fuel, food, and other shortages.

U-Boat attacks on convoys threatened to cut off England’s oil supply. In 1942, Royal Air Force ground crewmen refueled a Supermarine Spitfire Mark II. Photo courtesy Imperial War Museum.

By January of 1944, the American oilmen were credited with 94 completions and 76 producing oil wells. But not without cost. While working Rig No. 148, derrickhand Herman Douthit was killed when he fell from a drilling mast.

Douthit was buried with full military honors at the Cambridge American Cemetery.

The English Project contract was completed in March 1944 with the Americans logging 106 completions and 94 producers. England’s oil production had shot from 300 barrels of oil a day to more than 3,000 barrels of oil a day.

Without fanfare, the roughnecks returned to the United States and the families they had left a year before. Their mission and success remained secret until November 1944, when the Chicago Daily Tribune ran a story, “England’s Oil Boom,” on a back page. Few took notice at the time.

Honoring Oklahoma Roughnecks

By the end of the war, more than 3.5 million barrels of crude had been pumped from England’s “unsinkable tanker” oilfields. Petroleum industry expertise would again come into action – solving the challenge of oil pipelines across the English Channel – read about the operation in PLUTO, Secret Pipelines of WW II.

British Petroleum continued to produce oil from Dukes Wood until the field’s depletion in 1965.

The story remained largely unknown until the 1973 University of Oklahoma Press publication of The Secret of Sherwood Forest – Oil production in England during World War II by Guy and Grace Woodward. Then, Tony Speller, a member of Parliament, in 1989 visited Tulsa for a speaking engagement. He was given a copy of the book.

Surprised and intrigued by the story it told, Speller joined with members of the International Society of Energy Advocates, Noble Drilling Company employees, and others who believed that the singular accomplishment of this handful of Americans should be remembered. Artist Philip Jay O’Meilia was chosen to create a bronze tribute to these men.

O’Meilia, born in 1927 in Tulsa, Oklahoma, was inducted into the Oklahoma Hall of Fame in 1999. Interviewed for this article in 2012, he recalled ideas for the statue’s design quickly evolved.

“The notion of an ‘oil patch warrior’ soon developed…at parade rest with a roughneck’s best weapon – a Stillson wrench – instead of a rifle,” O’Meilia said. He also remembered how authenticity was critical, down to period gloves and hard hat.

“They even sent me a pair of original overalls so I would get it exactly right,” he explained in his interview with the American Oil & Gas Historical Society.

Those who look very closely will see the telltale impression of a pack of cigarettes in the oil patch warrior’s pocket. “Lucky Strike,” explained the artist with a laugh, because” Lucky Strike Green Has Gone to War!” was a advertising campaign at the time.

O’Meilia died in Tulsa on January 26, 2022, at age 94.

Statues dedicated in 1991 and 2001

In May 1991, Noble Drilling Corporation funded the return of 14 surviving oilmen to the dedication of O’Meilia’s seven-foot bronze Oil Patch Warrior in Sherwood Forest. Ten years after the ceremony in England, the citizens of Ardmore discovered that the original molds remained in O’Meilia’s Colorado foundry.

“Our mission was to create a memorial park that would honor those who sacrificed their lives, those who served in the military during times of war and peace, and the oil drillers and energy industry that came to England’s rescue in World War II,” explained Jack Riley, chairman of the Memorial Square committee.

O’Meilia recast the Sherwood Forest Oil Patch Warrior for Ardmore from the original molds. The statue was dedicated on November 10, 2001, with representatives from Noble Oil and Fain-Porter joining veterans at the ceremony. A brick walkway through Memorial Square displays the names of Ardmore area veterans.

“Memorial Square honors veterans who are responsible for the freedom we enjoy today – and the energy industry, which is responsible for the economic strength of our community,” declared Wes Stucky, president of the Ardmore Development Authority.

Adam Sieminski and wife Laurie visited the Sherwood Forest statue in 2005. Photo courtesy Adam Sieminski.

Time has taken away many of those on both sides of the Atlantic who struggled to preserve democracy. Fortunately, in these two imposing bronze Oil Patch Warriors, separated by an ocean of history, the story of the roughnecks of Sherwood Forest can always be remembered.

Editor’s Notes – Dukes Wood Oil Museum closed in 2021. Jay O’Melia’s Oil Patch Warrior (a replacement copy made of resin and stainless steel to deter scrap metal thieves) can be found in the Nottinghamshire countryside at Rufford Abbey Country Park.

American Oil & Gas Historical Society supporting member Adam Sieminski, past director of the Energy Information Administration, visited the original Sherwood Forest statue in 2005 and provided AOGHS with photos — and The Secret of Sherwood Forest — Oil Production in England During World War II. In August 2009, he helped sponsor the society’s participation in a two-day history field trip to Titusville, Pennsylvania (see the “Energy Economists Rock Oil Tour”.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Secret of Sherwood Forest: Oil Production in England During World War II (1973); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power

(2008). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information: Article Title – “Roughnecks of Sherwood Forest.” Author: Aoghs.org Editors. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-in-war/roughnecks-of-sherwood-forest. Last Updated: November 5, 2025. Original Published Date: November 28, 2012.