A giant Mid-Continent oilfield revealed in 1915 by the emerging science of petroleum geology.

Desperate for their town to live up to its name, community leaders of El Dorado, Kansas, sought petroleum riches after natural gas discoveries at nearby Augusta and at Paola, south of Kansas City. But it would be oil, not natural gas, that brought prosperity east of Wichita.

On the centennial of the October 1915 discovery well, the Butler County Times-Gazette noted the significance of the giant Kansas oilfield, which annually produced about 29 million barrels of oil just three years after its discovery.

A historic marker erected in 1940 at the Stapleton No. 1 well commemorates the October 5, 1915, scientifically discovered oilfield at El Dorado, Kansas. Photo by Bruce Wells.

“In 1915, about 3,000 people called the rural agricultural community of El Dorado home,” the newspaper reported. “They had no idea events toward the end of that year would begin something that would forever change not just El Dorado, but the state and an entire industry.”

Petroleum Geologists

The science of petroleum geology played a key role in discovering the El Dorado oilfield — and the many other Mid-Continent fields that followed. Drilled by Wichita Natural Gas, a subsidiary of Cities Service Company, the October 5 exploratory well revealed a 34-square-mile oilfield.

The Stapleton No. 1 well produced 95 barrels a day from 600 feet before being deepened to 2,500 feet to produce 110 barrels of oil a day from the Wilcox sands. Discoveries one year earlier in nearby Augusta had prompted El Dorado city fathers to seek a geological study of the area, according to Larry Skelton of the Kansas Geological Survey.

“Pioneers named El Dorado, Kansas, in 1857 for the beauty of the site and the promise of future riches but not until 58 years later was black rather than mythical yellow gold discovered when the Stapleton No. 1 oil well came in on October 5, 1915,” explained Skelton in his 1997 USGS Journal article.

By 1914 interest was growing in Butler county and south central Kansas. “A few positive finds had been made, but nothing exciting,” Skelton noted in “Striking It Big in Kansas” for the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG).

“Henry Doherty, founder of Cities Service in 1910, was seeking new gas reserves and opted for scientific exploration in lieu of wildcatting,” he wrote in the 2002 AAPG Explorer article.

After the giant El Dorado oilfield discovery in 1915, exploration companies increasingly realized the importance of petroleum geologists. Photo courtesy Kansas Oil Museum.

Doherty hired geologists Charles Gould and Everett Carpenter in Oklahoma and sent them to Augusta in Butler County. Gould had organized the Oklahoma Geological Survey in 1908 and served as its first director until 1911. According to Skelton, the geologists mapped prominent anticlinal structures in Permian Age limestone.

Finding Oil at Anticlines

By late 1914, several Augusta exploratory wells found commercial volumes of natural gas. Several wells also found oil. These developments “chafed El Dorado city fathers.”

According to geologist Skelton, drillers had unsuccessfully searched for hydrocarbons since the 1890s in the area about 15 miles northeast of Augusta. El Dorado city leaders decided to hire Erasmus Haworth, the state geologist and chairman of the University of Kansas geology department.

“He mapped a large anticline on the same formations used by Gould and Carpenter at Augusta and selected a site that proved to be a dry hole,” Skelton explained.

Undeterred, Cities Service subsidiary Wichita Natural Gas bought the town’s 790 leased acres for $800, verified Haworth’s work and began drilling in late September 1915. The Stapleton No. 1 well found oil within a week. “Using scientific geological survey methodology for the first time, Cities Service had identified a promising anticline,” Skelton noted, adding the field work outlined the El Dorado Anticline.

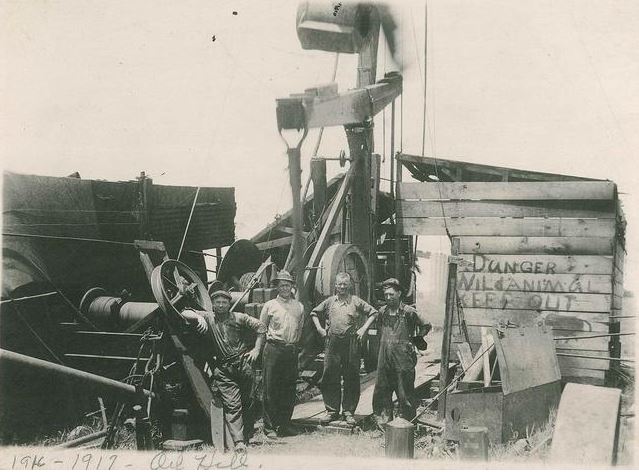

As Butler County wells multiplied, Oil Hill became the largest “company town” in the world with more than 8,000 residents. Photo courtesy Kansas Oil Museum.

Butler County’s geologic revelations encouraged Gulf Oil, Standard Oil, and other companies to acquire leases around Augusta and El Dorado. In addition to Henry Doherty, industry leaders like Archibald Derby, John Vickers and William Skelly established successful El Dorado oil-producing and refining companies.

“So the idea from that point forward, no oil company in the world would go and drill a well without seeking the advice of a geologist first,” proclaimed Warren Martin of the Kansas Oil Museum.

“Before 1915, geologists were seen in the same vein as witching and doodlebugs. They were just charlatans,” explained Martin in a 2015 Butler County Times-Gazette article on the centennial of Stapleton No. 1 well.

“It fundamentally transformed it from that point going forward,” Martin added. “Geology was established as one of the great science industries.” Learn more in Rocky Beginnings of Petroleum Geology.

Meanwhile, a 1903 well drilled on a farm near Dexter, Kansas, erupted as a “howling gasser,” and town residents gathered to celebrate the discovery of a natural gas field, which turned out to be helium (see Kansas “Wind Gas” Well). Many people had anticipated riches similar to towns in Ohio and Indiana, where natural gas supplied manufacturers during the Indiana Natural Gas Boom.

Kansas Drilling Boom

With the influx of thousands of workers after the El Dorado oilfield discovery, even Wichita accommodations were overwhelmed. Butler County’s population, about 23,000 in 1910, nearly doubled in 1920. To house its workers, Empire Gas & Fuel Company (formerly Wichita Natural Gas) built a 64-acre town northwest of El Dorado.

When the United States entered World War I, oil production escalated with the El Dorado field producing almost 29 million barrels of oil in 1918 — about nine percent of the nation’s oil.

The Kansas Oil Museum includes drilling and production equipment. The museum annually hosts a “Rockfest celebration of geology and oil and gas culture.” Photo by Bruce Wells

Although Oil Hill and its more than 8,000 residents, swimming pool, tennis courts and small golf course would disappear by the late 1950s, at the time it was called the largest “company town” in the world.

The Stapleton No. 1 well, which produced oil until 1967, can be visited by tourists — as can El Dorado’s Kansas Oil Museum, which includes 20 acres of rig displays, equipment exhibits and models of the region’s refinery history. The museum hosts events in an Energy Education Center, offers a variety of K-12 programs, and annually celebrates a “Rockfest” for aspiring geologists.

The Kansas museum’s pumping unit exhibits, the largest one on the grounds, educates visitors about evolving production technologies. It includes a 1970s pumpjack donated by Hawkins Oil Company. Visitors explore a variety of buildings depicting a typical petroleum boom town like Oil Hill.

The state’s earliest oil production began in 1892 at Neodesha in eastern Kansas — the first Kansas oil well — later proclaimed the first commercial discovery west of the Mississippi River. A natural gas well along the Oklahoma border at Caney, ignited in 1906 and took five weeks to bring under control (see Kansas Gas Well Fire).

Exploratoon and production exhibits welcome visitors to the Stevens County Gas & Historical Museum in Hugoton, a western Kansas community named in honor of French writer Victor Hugo.

In far western Kansas, the Hugoton Natural Gas Museum has preserved the history of a multistate natural gas geologic formation since 1961.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Fire in the Rock: A history of the oil and gas industry in Kansas, 1855-1976 (1976); History of Paola, Kansas

(1956); Caney, Kansas: The Big Gas City (1985); Anomalies, Pioneering Women in Petroleum Geology, 1917-2017 (2017); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Kansas Oil Boom.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/kansas-oil-boom. Last Updated: September 28, 2025. Original Published Date: October 4, 2015.