Once called “night riders of the hemlocks,” petroleum sleuths separated oil well fact from fiction.

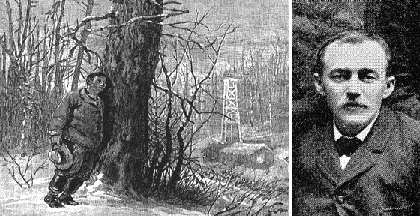

During the cold winter of 1888, 37-year-old oil scout Justus C. McMullen succumbed to pneumonia contracted while investigating oil production from a well in the wooded hills near Canonsburg, Pennsylvania.

McMullen, publisher of the Bradford “Petroleum Age” newspaper, already had contributed much to America’s early petroleum industry as a journalist and oilfield detective.

Oil scouts like Justus McMullen often braved harsh winters (and sometimes armed guards) to visit well sites. Their intelligence debunked rumors about oil wells.

The first U.S. oil well in 1859 launched a Pennsylvania drilling boom and created a new industry. With oil prices rising, margin trading of oil certificates became common, but unpredictable downturns ruined many a “black gold” fortune seeker. If a speculator believed prices would fall, he could sell short and turn a profit.

Optimism, pessimism and rumor influenced prices as trade in “paper oil” flourished at the early oil exchanges in Titusville, Oil City, and Petroleum Center. Enter the oil scout to separate oil production fact from fiction.

Night Riders

Since the petroleum industry’s earliest days, “scout tickets” have been the written reports of the progress of oil or natural gas wells drilling in the producing area, according to historian Robert Langenkamp of Cushing, Oklahoma. Scouting “tight holes” required more effort.

“The reports contain all pertinent information — all that can be found out by the enterprising oil scout; operator, location, lease, drilling contractor, depth of well, formations encountered, results of drill stem tests, logs, etc.,” Langenkamp explained in his 2018 Handbook of Oil Industry Terms & Phrases.

“On tight holes the scout is reduced to surreptitious means to get information” about the progress of the drilling, so the scout “talks to water hauler, to well-service people who may be talkative or landowner’s brother-in-law,” the author noted.

“The bird-dogging scout estimates the drill pipe set-backs for approximate depth; he notes the acid trucks or the shooting (perforating) crew; and through his binoculars, he judges the expressions on the operator’s face: happy or disgruntled,” reported Langenkamp, further explaining how modern oilfield detectives have worked since the 19th century.

Oilfield Detectives Association

Among the earliest of these detectives was a group that formed in Kinzua, Pennsylvania, in 1870 “for the purpose of exchange current and correct information about drilling wells,” according to the International Oil Scouts Association (IOSA), which was founded in 1924.

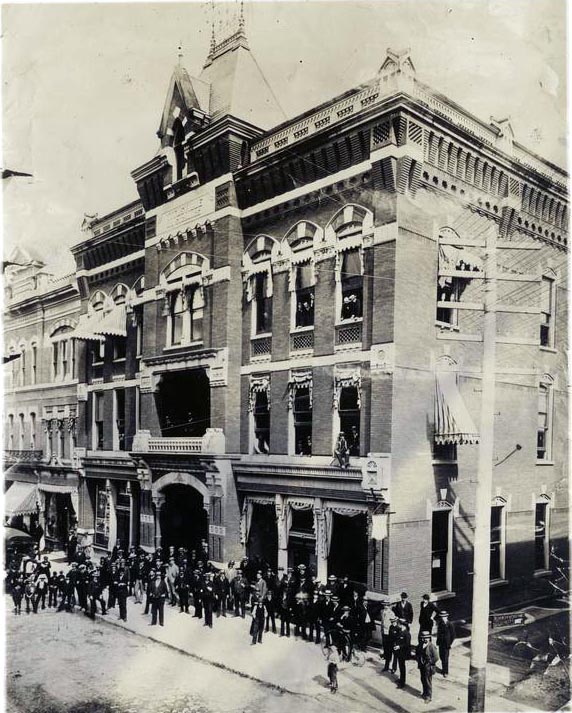

Prior to the Titusville Oil Exchange, above, established in 1871, producers gathered in convenient establishments, such as a Titusville hotel or along Centre Street in nearby Oil City — known as the “Curbside Exchange.”

Oilfield detecting as a profession arrived as oil pipelines came into wider use in Pennsylvania oilfields. A more efficient way of transporting oil, pipelines brought dramatic changes to the way oil was traded in the 1870s. As the petroleum industry grew complex – and risky – buyers and sellers became more wary.

With pipelines, instead of the oil buyer taking on-site delivery (in wooden barrels he provided), pipeline certificates were issued for oil delivery-in-kind at a negotiated price. These certificates could be bought and sold by anyone. Until Standard Oil Company stepped in and ended the practice.

Oil producers hired oil scouts to protect their investments from surreptitious market manipulation. Scouts searched for the facts about oil production.

As with all highly market-driven commodity industries, information and misinformation from speculators pushed prices erratically. Meanwhile, new oilfield discoveries added production as consumer demand for kerosene continued to grow.

Cherry Grove Mystery Well

Scouts debunked rumors, “demystified” reports about oil wells and secured accurate information on production (or lack thereof) – sometimes despite armed guards at drilling sites.

In 1881, Bradford, Pennsylvania, oilfields produced 83 percent of the United States total oil output. Prices plunged one year later when production from a single well was revealed at Cherry Grove Township. The Cherry Grove Mystery Well, drilled on lot 646 in Warren County southeast of Bradford, flowed 1,000 barrels of oil per day.

James Tennent, author of The Oil Scouts — Reminiscences of the Night Riders of the Hemlocks, explained that oil scouts, “saved the general trade thousands and millions by holding market manipulators in check.”

“Petroleum Age” Publisher

According to Tennett, Justus McMullen left a homestead farm in Orange County, New York, as a young man and eventually attended Cornell University to study civil engineering. His investigative skills took him to Pennsylvania oilfields.

McMullen began working in the petroleum industry as a reliable oil scout — and as the publisher of the “Petroleum Age” in the booming region around Bradford (also see Mrs. Alford’s Nitro Factory).

Justus McMullen’s dedication as an oil scout would lead to his early death on January 31, 1888, at the age of 37. The book History of the Counties of McKean, Elk, Cameron & Potter (1890) describes his final days in the Pittsburgh area:

When others telegraphed rumors and guesses, he stayed up all night secretly to run the gauge pole in mystery tanks. A week before his death he started out to collect the data for the monthly report of operation. There were conflicting reports regarding the Pittsburgh Manufacturers’ Gas Company’s well at Canonsburg, and to settle all doubts Mr. McMullen went to the well to get a gauge.

He was sick then. Other field men went out from Pittsburgh with him. They were told what the well was doing. This was good ‘hearsay,’ evidence, and as the thermometer stood several degrees below zero, the other field men went away satisfied with it. Not so with ‘Mac.’

For more than six hours, he waited there, chilled to the very marrow, until the well flowed again and he had gauged the flow. Then he went back to Pittsburgh sick. But he did not give up…though the pain he suffered was terrible. The data he brought home with him, and dictated to his loving wife from his deathbed, was as accurate and reliable as any ever gathered.

Even with such hard-earned information as McMullen’s, speculation in oil certificates continued to destabilize early oil markets, creating an intolerable burden on both oil producers and refiners. Standard Oil Company put an end to the era when it directed its subordinate, National Transit Company in Oil City, to cease issuing oil certificates.

Standard Oil set prices based on its view of supply and demand — stopping wildly fluctuating speculation, bringing the end of oil exchanges. The last of the oil exchanges to close was in Oil City in 1892. The building was later converted into a theater that featured the earliest U.S. motion pictures from Edison.

West Virginia Oil History

Oil scout McMullen was the great-uncle of David L. McKain (1934-2014), founding director of today’s Oil and Gas Museum in Parkersburg, West Virginia. He was named “Oilman of the Year” at the 2004 annual Sistersville Oil and Gas Festival.

Several floors of oilfield artifacts are exhibited in the Oil and Gas Museum in Parkersburg, West Virginia. 2005 photo by Bruce Wells.

A respected geologist and advocate of Parkersburg oil history, McKain was often seen trudging over hills and wading through mud to collect 19th-century oilfield artifacts. He wrote The Civil War and Northwestern Virginia — his second book about the history of West Virginia. His first book, Where It All Began, explored the history of the oil and natural gas industry in West Virginia and Southeastern Ohio.

McKain noted that his great-uncle, in addition to being a widely known and respected oil scout, was a pioneer in early industry trade publications. In 1883, as McMullen scouted wells in Warren and Forest counties, Pennsylvania, he became a part owner of the “Petroleum Age.”

According to the 2019 book Sketches in Crude Oil. Some Accidents and Incidents of the Petroleum Development in All Parts of the Globe, McMullen had previously written about the industry, including working for several newspapers in 1879. Sketches in Crude Oil author John J. McLaurin described McMullen’s oil patch reporting:

“His painstaking, conscientious reports were accepted as strictly reliable. He would trudge over the hills, wade through the miles of mud and ford swollen streams to ascertain the precise status of an important well, rather than approximate it from hearsay. This care and thoroughness gave the highest value to the statistical work of Justus C. McMullen.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Oil Scouts – Reminiscences of the Night Riders of the Hemlocks (1986); Handbook of Oil Industry Terms & Phrases (1988); Sketches in Crude Oil. Some Accidents and Incidents of the Petroleum Development in All Parts of the Globe (2019); Western Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage

(2008); Where it All Began: The story of the people and places where the oil & gas industry began: West Virginia and southeastern Ohio

(1994). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Oil Scouts – Oil Patch Detectives.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/oil-scouts. Last Updated: July 23, 2025. Original Published Date: December 1, 2006.