From the beginning of the U.S. oil industry, drilling stopped when a tool got stuck.

The petroleum industry’s difficult job of retrieving broken (and expensive) equipment obstructing an oil well — “fishing” — began in 1859 when a drilling tool stuck at 134 feet deep and ruined a Pennsylvania well. The technical challenges at far greater depths have tormented exploration companies ever since.

Just four days after the August 27, 1859, first U.S. oil discovery by Edwin L. Drake at Titusville, Pennsylvania, a much less known oil and natural gas industry pioneer began America’s second well to be drilled for petroleum. John Livingston Grandin dug his well nearby using a simple spring pole — but soon wedged his iron chisel downhole.

John L. Grandin attempted to recover a lost drill bit at his 1859 well near Tidioute, Pennsylvania. Warren County roadside marker photo.

The 22-year-old Grandin improvised his own well fishing tools, but not only lost his drill bit (an industry first), he ended up with America’s first dry hole among other petroleum industry milestones.

Searching for oil was less an earth science and more an art in the exploration and production industry’s earliest days. Geologists in Pennsylvania’s “valley that changed the world” knew far more about finding coal seams than characteristics of oil-bearing formations.

Making Hole

Even as drilling technologies evolved from spring poles and cable tools to modern rotary rigs, downhole problems remained — especially as wells reached new depths (learn more in Making Hole — Drilling Technology).

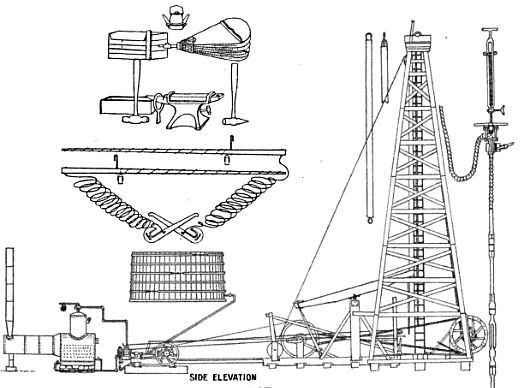

A 19th-century cable-tool rig, like its ancient predecessor the spring pole, utilized percussion drilling — the repeated lifting and dropping of a heavy chisel using hemp ropes. Drilling time and depth improved with the addition of steam power and tall, wooden derricks.

A standard, 82-foot cable-tool derrick used a steam boiler and one-cylinder engine connected to a “walking beam. Image from The Oil-Well Driller, 1905.

As depths increased, frequent stops were needed to bail out water and cuttings — and sharpen the bit’s iron edge. Small forges were often just feet from the well bore.

Despite drillers trying to avoid having expensive tools jammed deep in the well, accidents happened. The cable-tool rig’s manila rope or wire line would break. A pipe connection might bend. The downhole tool assemblies could no longer be lifted and dropped.

On the rig floor, fishing tools had to be lowered by a line into the well, armed at their end with spears, clamps and hooks. Sometimes a wood, wax and nails “impression block” was first lowered to get an idea of what lay downhole.

Hooks and Spears

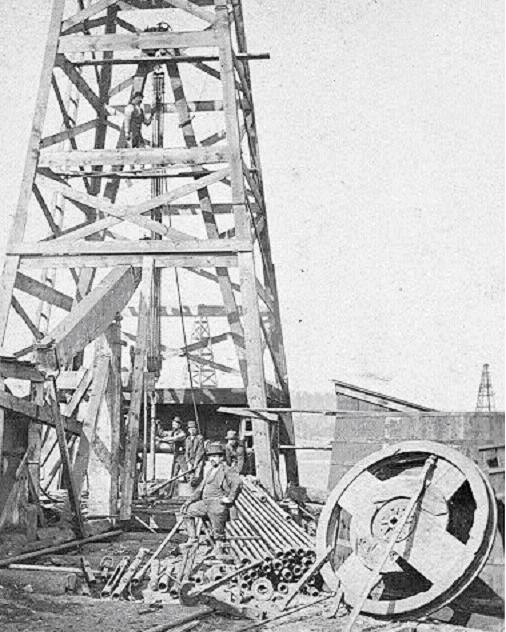

In percussion drilling, the heavy cable-tool assembly could get jammed in the borehole and could no longer be repeatedly lifted and dropped. In the foreground of the photograph below, the large wheel at right (with small, square hub) received the uppermost part of a fishing pole. A rope was wound around this wheel’s rim and led to the “bull wheel” shaft.

The term fishing came from early percussion drilling using cable tools. When the derrick’s manila rope or wire-line rope broke, a crewman lowered a hook and attempted to pull out the well’s heavy iron bit. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

Among the fishing tools at the man’s feet are 3.5-inch iron poles, each 20 feet in length and weighing 500 pounds. To fish for stuck tools, these were lowered in well, armed at their end with a “die” with a left-hand thread cut in it. This die fit over the end of the stuck tool, tapered inward slightly, and when turned to the left, cut a thread on the cable tool.

The bull wheel, driven by the well’s steam-powered drilling engine, exerted a tremendous strain on the assembled poles. Since that strain was always to the left, the die gradually cut a thread in the stuck cable tool. One of the cable tool sections would eventually “yield, unscrew, and be removed.”

The operation repeated until the lowest piece was reached. A “spud” was then employed. Drilling usually would continue into the night, illuminated by two-wicked “yellow dog” lanterns.

Knives and Whipstocks

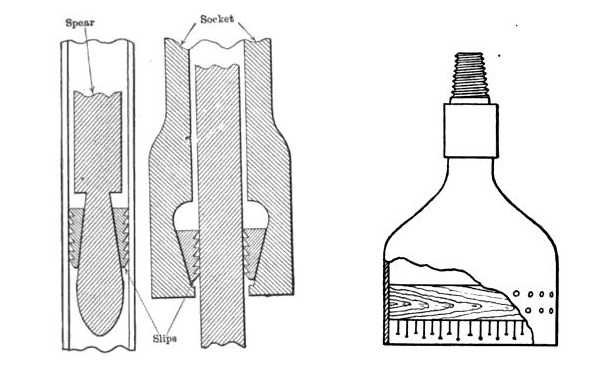

“Well fishing tools are constantly being improved and new ones introduced,” explained David T. Day in his A Handbook of the Petroleum Industry in 1922. Describing cable tool operations, he explained that the basic principle of well fishing tools often involved milled wedges — on a spear or in a cylinder — for recovering lost tubing or casing.

As drillers gained experience with deeper wells, patent applications included hundreds of designs for catching some tool or part that had been broken or lost in the borehole. Many of these “fishing tools” could be created on-site since most cable-tool rigs already had a forge for sharpening bits on the derrick floor.

Day noted that the simpler types of fishing tools comprised “horn sockets, corrugated friction sockets, rope grabs, rope spears, bit hooks, spuds, whipstocks, fluted wedges, rasps, bell sockets, rope knives, boot jacks, casing knives and die nipples.”

Basic fishing tools include the spear and socket, each with milled edges. Using nails and wax, an impression block helps determine what is stuck downhole. Image from A Handbook of the Petroleum Industry, 1922.

These and other devices, when used with an auger stem in various combinations called jars, can secure a powerful upward stroke or “jar” and thus dislodge and recover the tool being sought, Day explained in his 1922 book.

“The jars, essentially and universally used in fishing with cable tools, consist off two heavy forged-steel links, interlocking as the links of a cable chain, but fitting together more snugly,” he added.

“Many lost tools that cannot be recovered are drilled up or ‘side-tracked” (driven into or against the wall) and passed in drilling,” Day explained. Much depended upon “the skill and patience of the driller.”

Once all well fishing tools failed, a final resort was a whipstock, which allowed the bit to angle off and bypass the fish to leave the operator with a deviated hole. This was sometimes unpopular where wells were closely spaced.

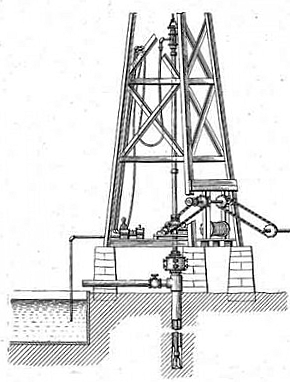

By the early 1900s, rotary drilling introduced the hollow drill stem that enabled broken rock debris to be washed out of the borehole. It led to far deeper wells.

As drilling with rotary rigs became more common in the early 1900s, fishing methods adapted. “In rotary drilling, the only tools ordinarily used in the well are the drill pipe and bits,” Day noted, adding that the rotary fishing tools, “were comparatively free from the complexities of cable-tool work.”

Most rotary fishing jobs were caused by “twist offs” (broken drill pipe), although the bit, drill coupling or tool joints may break or unscrew. As in cable-tool fishing, an impression block often was needed to determine the proper fishing tool.

But even back then — and especially now with wells miles deep and often turned horizontally — when a downhole problem occurred, the well could be lost for good.

Elk City, Deep Gas Capital

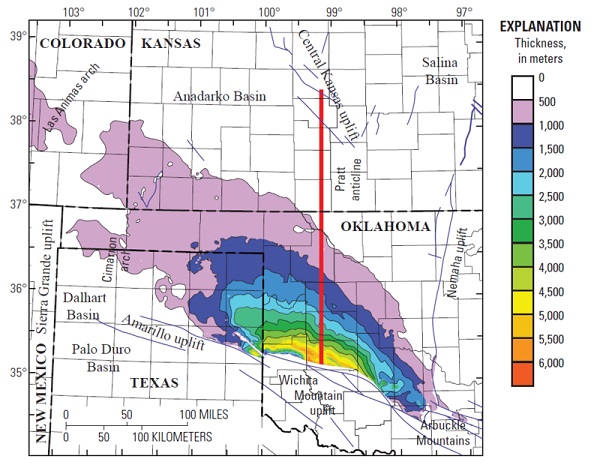

The Anadarko Basin extends across western Oklahoma into the Texas Panhandle and into southwestern Kansas and southeastern Colorado. It includes the Hugoton-Panhandle field, the Union City field and the Elk City field and is among the most prolific natural gas-producing areas in North America.

In 1980, the Oklahoma Historical Society and Oklahoma Petroleum Council dedicated a granite monument at Third and Pioneer streets in Elk City, Oklahoma. The Washita County marker notes:

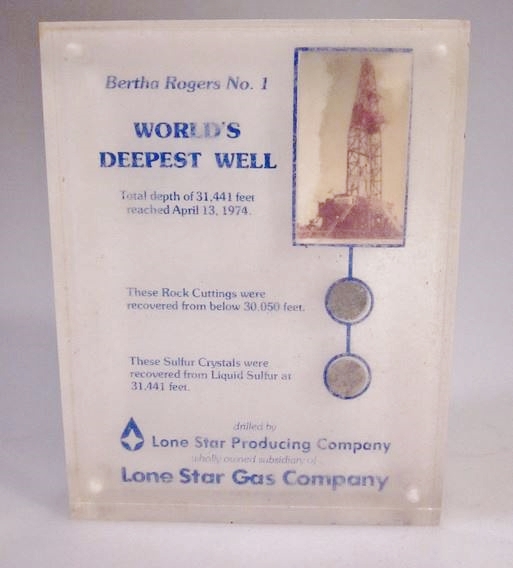

The Deep Anadarko Basin of Western Oklahoma is one of the most prolific gas provinces of North America. Wells drilled here have been among the world’s deepest. The Bertha Rogers No. 1 in Washita County, drilled in 1971 to 31,441 feet, was then the world’s deepest well. In 1979 the No. 1 Sanders well near Sayre became Oklahoma’s deepest gas producer at 24,996 feet.

When controls on gas prices were lifted, Anadarko justified the faith and perseverance of The GHK Company and other operators who pioneered in deep drilling. The shallow horizons of Greater Anadarko account for much of this nation’s proved gas reserves. Deeper sediments below 15,000 feet remain virtually unexplored. Renewed assessment of some 22,000 cubic miles of deep sediments may carry over into the 21st Century.

A 2014 geologic map of 50,000 square mile Anadarko Basin showing thickness of strata courtesy U.S. Geological Survey.

For the 20th century’s final quarter, the Basin remains the frontier of deep drilling technology centered on Elk City, “Deep Gas Capital of the World”. As gas prices equate more closely to value, the nation’s needs may be met increasingly from this massive sedimentary basin, a focal point in drilling innovation and geological interpretation.

In re-energizing America, Anadarko will not yield its gas easily or briefly. Promised rewards lying beyond the threshold of drilling techniques demand massive investment. In challenging the inventive enterprise of America’s energy industry, this Basin will remain the heartland of technology in penetrating the earth’s crust.

A 1974 souvenir of the Bertha Roger No. 1 well, which sought natural gas almost six miles deep in Oklahoma’s Anadarko Basin.

Until the 1960s, few companies could risk millions of dollars and push rotary rig drilling technology to reach beyond the 13,000-foot level in what geologists called “the deep gas play.”

The great expense and technological expertise necessary to complete ultra-deep natural gas wells at these depths made the Anadarko Basin “the domain of the major petroleum corporations,” explained Bobby Weaver, oil historian and frequent article contributor to the Oklahoma Historical Society.

GHK Company and partner Lone Star Producing Company believed ultra-deep wells in Oklahoma’s Anadarko Basin could produce massive amounts of natural gas. They began drilling wells more than three miles deep in the late 1960s.

South of Burns Flat in Washita County, their Bertha Rogers No.1 would reach almost six miles deep in 1974 — after a deep fishing trip.

Deep Fishing in Oklahoma

In March 1974 in far western Oklahoma, after 16 months of drilling and almost six miles deep, the Bertha Rogers No. 1 rotary rig drill stem sheared, leaving 4,111 feet of pipe and the drill bit stuck downhole. Spudded in November 1972 and averaging about 60 feet per day, the Bertha Rogers had been heading for the history books as the world’s deepest well at the time.

Independent producer John West in 2006 preserved artifacts in the closed Anadarko Basin Museum of Natural History in Elk City, Oklahoma. Photo by Bruce Wells.

It was March 1974 and the enormous investment of Lone Star Producing Company of Dallas, and partner GHK Company of Oklahoma City, was about to be lost. Desperate GHK executives turned to a “fishing” company in Texas.

Millions of dollars hung in the balance when Houston-based Wilson Downhole Service Company, was called and tool-fishing expert Mack Ponder sent to the rescue.

Against all odds and employing the latest 1970s technology, Ponder was able to retrieve the pipe sections and drill bit from 30,019 feet down, bringing operations back online and enabling drilling to continue even deeper into Oklahoma’s Anadarko Basin, at a site about 12 miles west of Cordell.

Although the remarkable deep fishing achievement was celebrated, the Bertha Rogers No. 1 had to be completed at just 14,000 feet after striking molten sulfur at 31,441 feet. The equipment could not take the abuse at total depth. The well set a world record and remains one of the deepest ever drilled.

Completed at a depth of almost 25,000 feet, the Beckham County well would become Oklahoma’s deepest natural gas producer (also see Anadarko Basin in Depth`).

Oil Well Fishing Tool Technician

The U.S. Labor Department describes an “Oil Well Fishing Tool Technician” (Occupational Title 930.261-010) as an occupation that “analyzes conditions of unserviceable oil or gas wells and directs use of special well-fishing tools and techniques to recover lost equipment and other obstacles from boreholes of wells,”

The government description adds that the technician plans fishing methods, selects tools, and “directs drilling crew in applying weights to drill pipes, in using special tools, in applying pressure to circulating fluid (mud), and in drilling around lodged obstacles or specified earth formations, using whipstocks and other special tools.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: History Of Oil Well Drilling (2007); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (1991); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Fishing in Petroleum Wells.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-art/high-flying-trademark. Last Updated: December 28, 2024. Original Published Date: June 1, 2006.