Powered by a diesel-electric engine in 1934, a streamliner cut steam locomotion travel time by half.

“Once I built a railroad, I made it run, made it race against time. Once I built a railroad; now it’s done. Brother, can you spare a dime?” — Bing Crosby, 1932.

By the early 1930s, America’s passenger railroad business was in deep trouble. In addition to the Great Depression, the once-dominant transportation industry faced growing competition from automobiles. New refineries produced vast amounts of gasoline, thanks to giant oilfield discoveries like Spindletop Hill in Texas.

Diesel-electric engines pioneered by General Motors and Winton Engine Company saved America’s railroad passenger industry with a four-fold power-to-weight gain. Photo courtesy Model Railroader magazine, January 1999.

Despite the hard economic times, gasoline fueled more than 30 million cars, trucks, and buses on U.S. roads (many without asphalt paving).

Locomotive Power

Primitive diesel engines of the day remained heavy and slow, but a powerful railroad diesel-electric engine was in the future. It had been 60 years since coal-burning steam locomotives and the transcontinental railroad had linked America’s east and west coasts on May 10, 1869.

Used since about 1925, diesel engines were heavy — producing only a single horsepower from 80 pounds of engine weight.

Meanwhile, railroad steam engine technology had advanced since the “golden spike” of 1869 in Promontory Point, Utah. But locomotives still “belched steam, smoke, and cinders,” noted one railroad historian, adding, “Passengers often felt like they had been on a tour of a coal mine.”

The two streamliner trains that changed America’s railroad industry in the late 1930s: Union Pacific M-10000 (left) and Burlington Zephyr. The Zephyr has been preserved as an exhibit at the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry. Photo courtesy Union Pacific Museum.

While most U.S. locomotives were still steam-powered, General Electric in 1913 designed and built the first commercially successful gasoline-powered engine locomotive. Two General Motors 175-horsepower V-8s powered two 600-volt, direct current generators. They propelled the 57-ton locomotive to a top speed of 51 miles per hour.

The locomotive Dan Patch, considered by many to be the first successful internal combustion engine locomotive in the United States.

The Electric Line of Minnesota Company purchased the new gasoline-powered electric hybrid for $34,500. Marketing executives picked the name Dan Patch. a world-champion harness horse at the time. By 1930, powerful diesel engines with electric generators transformed train travel with streamliners.

Distillate Engines

In rail yards, low-geared diesels had been used from about 1925, mainly as engines for “switcher” locomotives used for maneuvering, but they were slow, according to historian Richard Cleghorn Overton. Powerful distillate-burning engines proved heavy and difficult to maintain.

The powerful diesel-electric Zephyr arrived in 1934; its technology was a result of the Navy’s search for an improved submarine engine.

Overton, author of Burlington Route: A History of the Burlington Lines, noted the burning fuels ranged from a low-grade gasoline to painter’s naphtha and diesel.

The distillate railroad engines emitted an oily smoke and often produced only a single horsepower from 80 pounds of engine weight. The common four-stroke engines fouled easily and required multiple spark plugs per cylinder.

Help for America’s failing passenger railroads would come from U.S. Navy diesel-electric engine technology, wrapped in a stainless steel Art Deco locomotive.

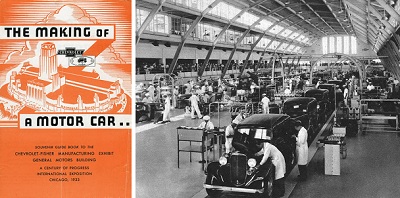

New diesel-electric engines generated power for the “Making of a Motor Car” exhibit at the 1933 Century of Progress fair in Chicago. The assembly line fascinated visitors who watched from overhead galleries.

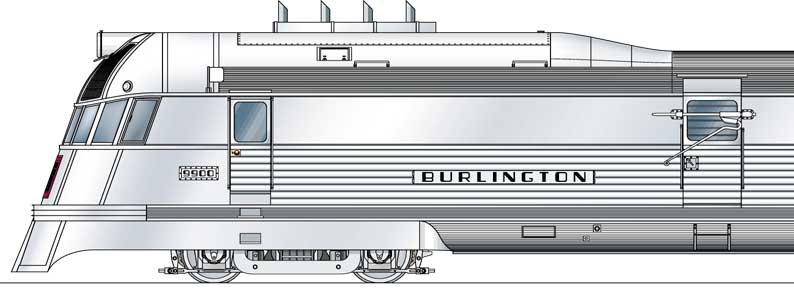

“Wings to the Iron Horse…Burlington pioneers again — the first diesel streamline train,” proclaimed passenger rail advertisements in the 1930s. The long-awaited technology for railroad diesel-electric engines had arrived.

Diesel-Electric Hybrid

With the Nazi threat and war on the horizon, the U.S. Navy needed a lighter-weight, more powerful diesel engine for its submarines. The Navy also recognized it had been too slow in converting its surface vessels from coal to fuel oil (see Petroleum and Sea Power). General Motors joined the nationwide competition to develop a new diesel engine for the Navy.

Seeking engineering and production expertise, in 1930 GM acquired the Winton Engine Company of Cleveland, Ohio. Winton, established in 1896 as Winton Bicycle Company, was an early automobile manufacturer. Winton Engine Company evolved into a developer of engines for marine applications, power companies, pipeline operators — and railroads.

With GM’s financial backing, Winton engineers designed a radical new two-stroke diesel that delivered one horsepower per 20 pounds of engine weight. It provided a four-fold power to weight gain.

The Model 201A prototype — a 503-cubic-inch, 600 horsepower, 8-cylinder diesel-electric engine — used no spark plugs, relying instead on newly patented high-pressure fuel injectors and a 16:1 compression ratio for ignition.

Powered by an eight-cylinder Winton 201A diesel engine, the revolutionary streamliner traveled the 1,015 miles from Denver to Chicago in just over 13 hours — a passenger train record.

At Chicago’s Century of Progress World’s Fair in 1933, GM evaluated two railroad diesel-electric engines, using them to generate power for its “Making of a Motor Car” exhibit. The working demonstration of a Chevrolet assembly line fascinated thousands of visitors who watched from overhead galleries.

The Burlington Line

One visitor happened to be Ralph Budd, president of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad (known as the Burlington Line). Budd recognized the locomotive potential of these extraordinary new diesel-electric power plants. He saw them as a perfect match for the lightweight “shot-welded” stainless steel rail cars pioneered by the Edward G. Budd (no relation) Manufacturing Company in Philadelphia.

Edward Budd pioneered supplying all-steel bodies to the automobile industry in 1912. His success in steel stamping technology made the production of them cheaper and faster. By 1925, his system was used to produce half of all U.S. auto bodies.

However, the Depression put the Budd Manufacturing Company almost $2,000,000 in the red — prompting its fortuitous diversification into the railroad car market to generate revenue. When approached by Burlington President Ralph Budd in 1933, this Budd was ready.

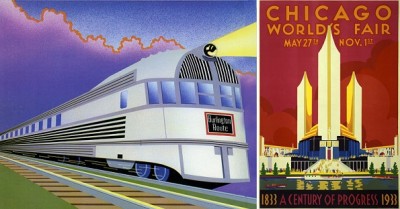

Chicago World’s Fair visitors line up to admire the stainless steel beauty of the Burlington Zephyr, which will soon be featured in a Hollywood movie. Eight major U.S. railroads soon convert to efficient diesel-electric locomotives. Photo from a Burlington Route Railroad 1934 postcard.

Within a year, the two technologies were successfully merged with the creation of the Winton 201A-powered Burlington Zephyr, America’s first diesel-electric train. It would change railroad transportation history.

Submarine Engines

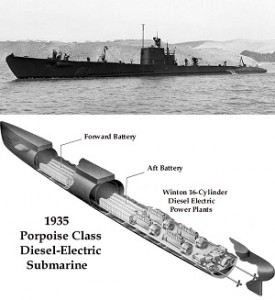

General Motors in 1932 won the Navy’s competition for a lightweight and powerful diesel-electric. The Navy decided a 16-cylinder Winton would power a new class of submarines.

Winton diesel-electric engines powered a new generation of U.S. submarines. The first of its class, Porpoise (SS-172), joined the fleet in 1935 and served throughout World War II.

In 1935, the USS Porpoise became the first to join the fleet, and it served throughout World War II. All of the silent-service’s diesel-electrics power plants descended from the Burlington Zephyr. They would remain part of the fleet until replaced by nuclear propulsion.

The Speedy Zephyr

When the Zephyr rolled into Chicago’s Century of Progress exhibition on May 26, 1934, it ended a nonstop 13-hour, 4-minute, and 58-second “dawn to dusk” promotional run from Denver. Powered by a single eight-cylinder Winton 201A diesel, the streamliner cut average steam locomotive time by half.

The Zephyr had traveled 1,015 miles at an average speed of 76.61 miles per hour, It often sped along the route in excess of 112 mph — amazing lines of trackside spectators. Crowds of Zephyr-watchers could be found from Colorado to Illinois.

During its record-breaking run, the Zephyr burned just $16.72 worth of diesel fuel (about four cents per gallon). The same distance in a coal steamer would have cost $255. Construction innovations included the specialized shot-welding that joined sheets of stainless steel.

Further, the lightweight steel resisted corrosion so it didn’t have to be painted.

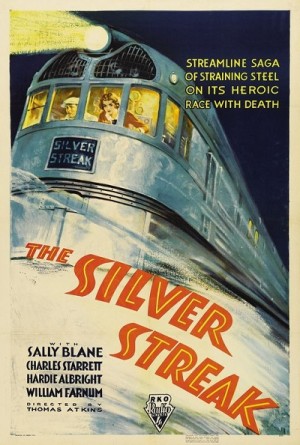

Considered a 1934 “B” movie — intended for the bottom half of double features — ”The Silver Streak” would remain a favorite of many railroad history fans.

Americans fell in love with the Zephyr. Four months after its high-speed appearance at Chicago’s Century of Progress, the streamliner made its 1934 Hollywood film debut, starring as “The Silver Streak” for an RKO picture.

Burlington loaned its Zephyr for the movie’s filming. Repainted, the company logo on the front became the Silver Streak. “The streamlined train, platinum blonde descendant of the rugged old Iron Horse, has been glorified by Hollywood in the modern melodrama,” proclaimed the New York Times.

Surprisingly, the black-and-white “B” movie came and went without drawing many theatergoers. But it has since won its place in movie history as a rail-fan favorite, according to a 2001 article in the Zephyr Online. “It did have a lot of action, and the location shots of the Zephyr are an interesting record of this pioneer.”

The RKO film should not be confused with 20th Century Fox’s 1976 comedy “Silver Streak” filmed in Canada using Canadian Pacific Railway equipment from the Canadian, a transcontinental passenger train.

End of Steam

Meanwhile, by the end of 1934, eight major U.S. railroads had ordered diesel-electric locomotives. The engine technology’s cost advantages in manpower, maintenance, and support were quickly apparent.

Despite the greater initial cost of diesel-electric, a century of steam locomotive dominance soon came to an end. By the mid-1950s, steam locomotives were no longer being manufactured in the United States.

A Zephyr competitor, the Union Pacific M-10000 built by the Pullman Car & Manufacturing Company, also showcased railroad diesel-electric engine technology at the Century of Progress World’s Fair in Chicago.

In fact, the aluminum M-10000 streamliner was revealed six weeks earlier than the Zephyr. Recognized as America’s first streamliner, the M-10000 was cut up for scrap in 1942. The Zephyr (later renamed the Pioneer Zephyr) ended up on display at the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Burlington Route: A History of the Burlington Lines (1965); Burlington’s Zephyrs, Great Passenger Trains (2004); The Great Railroad Revolution: The History of Trains in America

(2013). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Adding Wings to the Iron Horse.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/transportation/adding-wings-to-the-iron-horse. Last Updated: May 21, 2025. Original Published Date: April 29, 2014.