by Bruce Wells | Oct 15, 2025 | Petroleum Companies

Hard lessons learned in the Wyoming Powder River Basin.

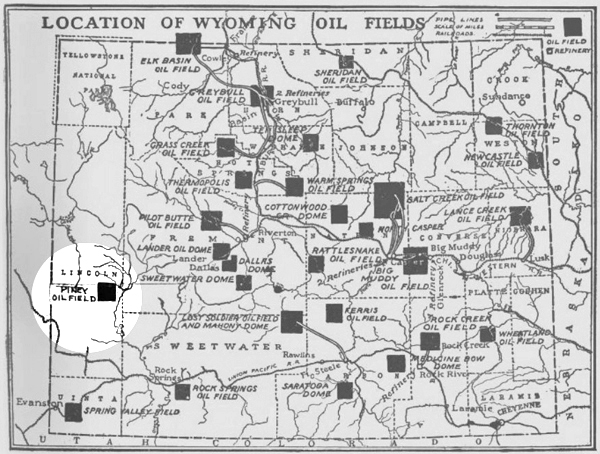

During World War I, the Winona Oil Corporation set up operations in Casper, Wyoming, with holdings of 1,200 acres of “selected land in the heart of Powder River.” The small, newly established exploration company reported having one drilling rig and another ready to be “rigged up” at another site.

A Winona Oil Company station sold gasoline and and Ivaline Motor Oil, circa 1919. After months of difficult drilling, the company’s first exploratory well reached a depth of 700 feet without finding oil.

As the Powder River Basin attracted exploration companies, a 1918 discovery at a depth of about 2,600 feet by the Ohio Oil Company (later Marathon) would grow into the largest in the Rocky Mountains. Ohio Oil could afford drilling more productive wells a thousand feet deeper.

Along with earlier discoveries at Salt Creek (1908) and Big Muddy (1916), the Lance Creek field “brought an immediate boom and derricks sprang up everywhere,” according to the Niobrara Historical Society. The Basin’s abundant shale deposits also played a role.

With capitalization of $200,000, Winona Oil was considered a “poor boy” drilling venture dependent upon investors to fund continued drilling despite the risks. The company offered stock at 5 cents a share. Advertisements in the Ogden Standard enticed investors with “Winona Is Here to make Money, Money, Money.”

In February 1918, C. Kirchner, secretary of the Winona Oil, conducted a promotional demonstration of the reduction of shale oil to gas for about 50 onlookers. “This gas was lighted and burned during the entire experiment to such an extent that a couple of engineers in the party made the remark that the gas itself would furnish 90 percent of the fuel necessary for the original reduction,” it was later proclaimed.

This Winona Oil interest in shale oil did not develop, although other contemporary ventures did pursue it (see Ute Oil Company).

Powder River Oilfield

Winona Oil by 1919 had only been able to drill 700 feet in its first drilling effort somewhere “on the north side of the railroad.”

“Hocus Pocus-or-Common Sense?” Ivaline Motor Oil sales did not help the Winona Oil Company to survive its drilling ventures in the highly competitive oilfields of the Powder River Basin.

In March 1919, a trade magazine noted that “the Powder River Syndicate has undertaken to finish the well commenced by the Winona Oil Corporation at Powder River, Natrona Co., according to reports current in Casper.”

Another article in the Oil & Gas News added, “In the Powder River field, the Winona Oil Corporation has announced the purchase of a drilling machine which will be used to complete the company’s first well, which has been underway for months. The Winona claims to have solved all its difficulties and expects to go with its work without further delay.”

By the end of May, Winona Oil Company reportedly survived its financial difficulties and had reentered the field. Plans were by then underway to drill a second well.

Good news came the following month when the first well was described as “gassing heavily, and Casper people interested in the enterprise are very optimistic over the prospects,” the trade publication proclaimed, adding. “Should the well prove a good one, a large tract north of Powder River station would be added to the territory considered proven.”

However, by August the good news had gone bad; the gasser well had to be abandoned, “as the hole was started with a casing too small to see it thoroughly.”

Powder River Syndicate

A second well was spudded by the Powder River Syndicate with Winona Oil a fifty-fifty partner. “The Winona Powder River Syndicate well No. 2, which was begun when the first hole pinched-out, is making 100 feet a day, according to reports from the field, and is down about 500 feet. This well is located north of Powder River, on Winona holdings,” noted the Oil & Gas News on September 4.

The publication reported bad news on January 29, 1920. “The Winona well at Powder River is also shut down, but it is claimed that drilling will resume in the spring,” the News noted. “This is the second well, the first having been lost on account of a bit wedged in the hole.”

Drilling did not resume in the spring or anytime thereafter. Despite the efforts of Winona Oil and the hopes of its investors, the independent exploration company did not survive. Cities Service Company bought Winona Oil and moved the Winona division to St. Paul, Minnesota.

More articles about small exploration and production companies attempting to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

______________________

Recommended Reading: Black Gold, Patterns in the Development of Wyoming’s Oil Industry (1997); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an annual AOGHS supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Winona Corporation.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/winona-oil-corporation. Last Updated: October 18, 2025. Original Published Date: March 23, 2016.

by Bruce Wells | Dec 3, 2013 | Petroleum Companies

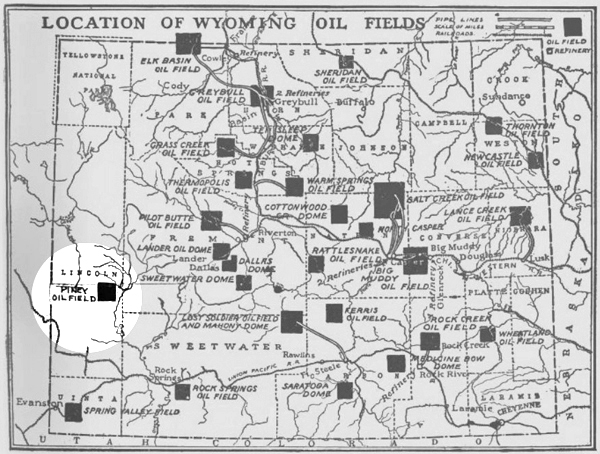

“The occurrence of oil in southwestern Wyoming has been known for nearly three-fourths of a century,” reported the U.S. Geological Survey in 1914.

Alfred Reginald Schultz, author of Geology and Geography of a Portion of Lincoln County, Wyoming, noted that early trappers and fur traders regularly visited oil springs.

“The first published account of oil in southwestern Wyoming resulted from an examination made by the Mormons in 1847 on their pioneer journey across the great plains,” he added.

Although the oil from springs in Uinta and Lincoln counties was dark and heavy, its low sulfur content convinced Schultz, “this petroleum is one of the most valuable that I have ever examined.”

Ranchers used the oil as machine oil and it “proved highly satisfactory,” he added. “It did not rise to the surface, but appeared to drain into the soil that filled the valley; at several points oil was encountered by sinking shallow wells a few feet into this soil.”

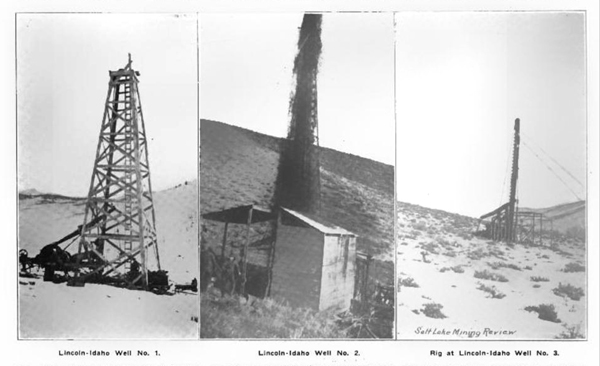

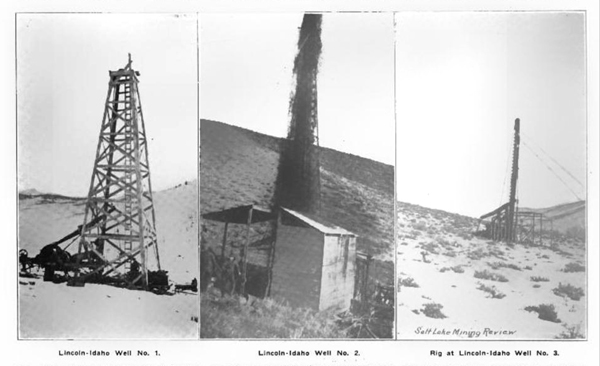

Needless to say, this 1914 USGS report inspired independent petroleum companies to drill in southwestern Wyoming. One of them, Lincoln-Idaho Oil Company, drilled an exploratory well that showed sufficient promise to prompt drilling of a second well nearby on the company’s Big Piney lease.

This well number two, called the “Lackey Well,” in August 1919 produced a gusher from less than 1,000 feet deep. The well was “a sensation in western Wyoming oil circles” according to the Salt Lake Mining Review.

“In February of 1919 Mr. Lackey brought in a third well about three-quarters of a mile north of his first attempt,” noted a 1920 article in the Salt Lake Mining Review, which included these images.

Unfortunately, Lincoln-Idaho Oil would not be among those to succeed in the Big Piney.

Under company President Thomas Clinton, Lincoln-Idaho spudded its third well and a fourth about six miles south of Kemmerer, Lincoln County, where Clinton maintained an office. Capitalized at $500,000, the company was authorized to sell 250,000 shares of stock. Commissions were limited to 25 percent, but zealous reporting of the company’s drilling success generated enough sales to sustain drilling operations.

In 2000, the massive top section of a circa 1955 production derrick was moved to a Big Piney park, “as a tribute to the contributions made by the oil and gas industry to the community,” which decorates it for Christmas. Photo by Dawn Ballou.

“If you want to make some easy money, this is your opportunity,” declared a newspaper advertisement as the company’s stock sold for 21 cents per share and its crude oil production settled at about 100 barrels a day. The remoteness of the Big Piney oilfield from any railroad transportation made small production operations like Lincoln-Idaho Oil Company very risky.

“The Lincoln-Idaho Oil Company, the largest operator in the Big Piney field, Lincoln County, will do no more drilling…but will hereafter be classed as a holding company,” the Oil & Gas News reported in 1921.

An unsuccessful effort to amend the company’s oil prospecting permit in 1922 was litigated until 1925, ending in a judgment for the Department of the Interior and against Lincoln-Idaho Oil. Thereafter, the company disappears, leaving only collectible stock certificates behind.

Learn more in First Wyoming Oil Wells.

Exploring Southwestern Wyoming

“Going back to 1847, heavy oil from a seep at Fossil and Spring Valley was reported to have been used for greasing wagons, and ranchers and cowboys,” explained Barbara McKinley of the Green River Valley Museum.

Oil from a seep at Birch Creek was seen on horses’ hooves in 1892.

According to McKinley, geologists had surveyed the east side of the Wyoming Range early in the 20th century and predicted a positive outlook for oil production. Natural gas there at that time had no value – at least there was no market.

Although several companies began drilling in Lincoln County and neighboring Sublette County in 1904, “activity really began taking off in earnest during the late teens,” she reported in a 2003 article for the Sublette Examiner.

“Charlie Budd and Charles Lackey were busily promoting the Dry Piney area and brought in Cretaceous Well No. 1, but bad luck seemed to dog their efforts,” said McKinley.

The Green River Valley Museum began in 1990 thanks to the Big Piney Centennial Committee. Barbara McKinley (June 9, 1933 – Dec. 28, 2011) served on the first board of directors of the museum.

W.D. “Bill” Newlon was drilling, and the Lincoln-Idaho No. 2 well reported a “good flow” of oil in 1919, she noted. “Everything was off to the races by the 1920s.”

But trouble loomed for Lincoln-Idaho Oil Company and others.

“Right at this time, turmoil also developed in the area when in 1920, the federal government changed the method governing oil and gas drilling and ownership rights from placer law to a lease system,” McKinley explained. “Prior to that time, placer mining law, such as that used for gold, covered the rights to find and produce oil.”

A person or company had to discover oil in commercial quantities before being able to secure title to the claim. Title was granted to the person striking oil first and anyone else drilling on the claim lost out.

“Some companies who were working to prove up on their claims lost out as other individuals or companies rushed to lease up the land from under them,” McKinley concluded. Visit the Green River Valley Museum in Big Piney.

___________________________________________________________________________________

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this AOGHS.ORG energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2018 Bruce A. Wells.