Nylon, a Petroleum Polymer

Revolutionary DuPont lab product first used commercially in 1938 for toothbrush bristles.

The world’s first synthetic fiber was the petroleum product “Nylon 6,” discovered in 1935 by a DuPont chemist who produced the polymer from chemicals found in oil.

DuPont Corporation foresaw the future of “strong as steel” artificial fibers. The chemical conglomerate had been founded in 1802 as a Wilmington, Delaware, manufacturer of gunpowder. The company would become a global giant after its scientists created durable and versatile products like nylon, rayon and lucite.

“Women show off their nylon pantyhose to a newspaper photographer, circa 1942,” noted historian Jennifer S. Li in “The Story of Nylon – From a Depressed Scientist to Essential Swimwear.” Photo by R. Dale Rooks (1917-1954).

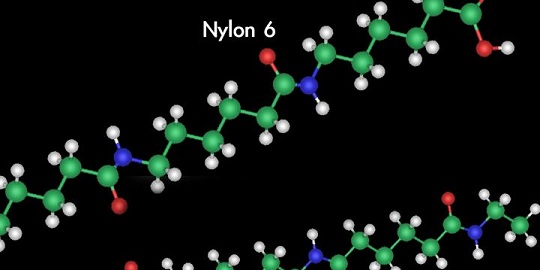

The world’s first synthetic fiber — nylon — was discovered on February 28, 1935, by a former Harvard professor working at a DuPont research laboratory. Called Nylon 6 by scientists, the revolutionary carbon-based product came from chemicals found in petroleum.

Chemists called the man-made fiber Nylon 6 because chains of adipic acid and hexamethylene diamine each contained six carbon atoms per molecule.

Professor Wallace Carothers had experimented with artificial materials for more than six years. He previously discovered neoprene rubber (commonly used in wet suits) and made major contributions to understanding polymers — large molecules composed in long chains of repeating chemical structures.

Polymer Chains

Carothers, 32, created fibers when he combined the chemicals amine, hexamethylene diamine, and adipic acid. His experiments formed polymer chains using a process in which individual molecules joined together with water as a byproduct. But the fibers were weak.

A PBS series, A Science Odyssey: People and Discoveries, in 1998 noted Carothers’ breakthrough came when he realized, “the water produced by the reaction was dropping back into the mixture and getting in the way of more polymers forming. He adjusted his equipment so that the water was distilled and removed from the system. It worked!”

DuPont named the petroleum product nylon — although chemists called it Nylon 6 because the adipic acid and hexamethylene diamine each contain six carbon atoms per molecule.

Each man-made molecule consists of 100 or more repeating units of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms, strung in a chain. A single filament of nylon may have a million or more molecules, each taking some of the strain when the filament is stretched.

There’s disagreement about how the product name originated at DuPont.

“As to the word nylon, it’s actually quite arbitrary. DuPont itself has stated that originally the name was intended to be No-Run (that’s run as in the sense of the compound chain of the substance unravelling), but at the time there was no real justification for the claim, so it needed to be changed,” noted Chris Nickson in a 2017 website post, Where Does the Name Nylon Originate?

Toothbrush Bristles

The first commercial use of this revolutionary petroleum product was for toothbrushes.

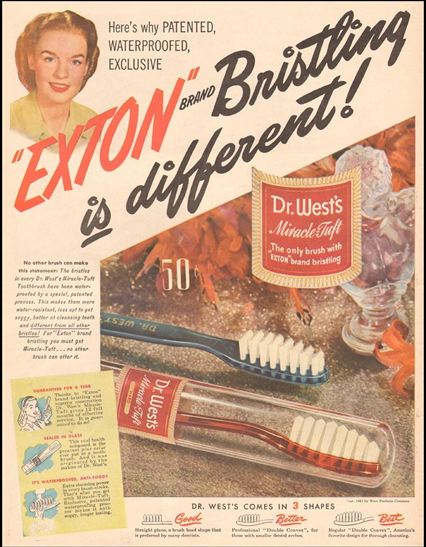

On February 24, 1938, the Weco Products Company of Chicago, Illinois, began selling its new “Dr. West’s Miracle-Tuft” — the earliest toothbrush to use synthetic DuPont nylon bristles.

First used for toothbrush bristles, nylon women’s stockings were promoted in a DuPont 1948 ad.

Americans will soon brush their teeth with nylon — instead of hog bristles, declared an article in the New York Times. “Until now, all good toothbrushes were made with animal bristles,” explained a 1938 Weco Products advertisement in Life magazine.

“Today, Dr. West’s new Miracle-Tuft is a single exception,” the ad proclaimed. “It is made with EXTON, a unique bristle-like filament developed by the great DuPont laboratories, and produced exclusively for Dr. West’s.”

Pricing its toothbrush at 50 cents, the Weco Products Company guaranteed, “no bristle shedding.” Johnson & Johnson of New Brunswick, New Jersey, will introduce a competing nylon-bristle toothbrush in 1939.

Nylon Stockings

Although DuPont patented nylon in 1935, it was not officially announced to the public until October 27, 1938, in New York City.

A DuPont vice president unveiled the synthetic fiber — not to a scientific society or industry association — but to 3,000 Women’s Club members gathered at the site of the upcoming 1939 New York World’s Fair.

“He spoke in a session entitled ‘We Enter the World of Tomorrow,’ which was keyed to the theme of the forthcoming fair, the World of Tomorrow,” explained DuPont historian David A. Hounshell in a 1988 book.

The petroleum product was an instant hit, especially as a replacement for silk in hosiery. DuPont built a full-scale nylon plant in Seaford, Delaware, and began commercial production in late 1939. The company purposefully did not register “nylon” as a trademark – choosing to allow the word to enter the American vocabulary as a synonym for “stockings.”

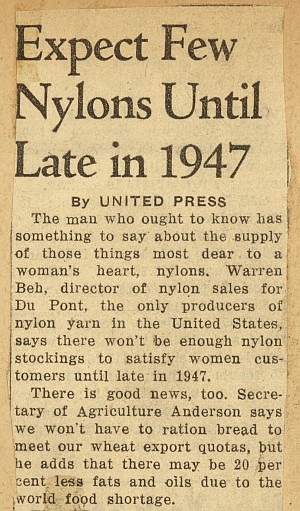

Women’s nylon stockings appeared for the first time at Gimbels Department Store on May 15, 1940. World War II would remove the polymer hosiery to make nylon parachutes and other vital supplies.

Nylon would become far and away the biggest money-maker in the history of DuPont. The powerful material from lab research led company executives to derive formulas for growth, according to Hounshell in The Nylon Drama.

“By putting more money into fundamental research, Du Pont would discover and develop ‘new nylons,’ that is, new proprietary products sold to industrial customers and having the growth potential of nylon,” Hounshell explained in his 1988 book.

Carothers did not live to see the widespread application of his work — in consumer goods such as toothbrushes, fishing lines, luggage and lingerie, or in special uses such as surgical thread, parachutes, or pipes — nor the powerful effect it had in launching a whole era of synthetics.

Devastated by the sudden death of his favorite sister in early 1937, Wallace Carothers committed suicide in April of that year. The DuPont Company would name its research facility after him.

The DuPont website notes that the invention of nylon changed the way people dressed worldwide and made the term ‘silk stocking’ obsolete (once an epithet directed at the wealthy elite). Nylon’s success encouraged DuPont and other companies to adopt long-term strategies for products developed from research.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Golden Thread: How Fabric Changed History (2019); Enough for One Lifetime: Wallace Carothers, Inventor of Nylon (2005); The Nylon Drama (1988). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Nylon, a Petroleum Polymer.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/products/petroleum-product-nylon-fiber. Last Updated: February 21, 2025. Original Published Date: February 23, 2014.