New companies rush to drill at Spindletop Hill in early 1900s.

When a geyser of oil erupted in 1901 on Spindletop Hill, near Beaumont, Texas, it launched the greatest oil boom in America — far exceeding the nation’s first commercial oil well in 1859.

Many new and inexperienced oil ventures were formed almost overnight, including Buffalo Oil Company. The Spindletop field produced 43 million barrels of oil in its first four years, helping to launch the modern petroleum industry.

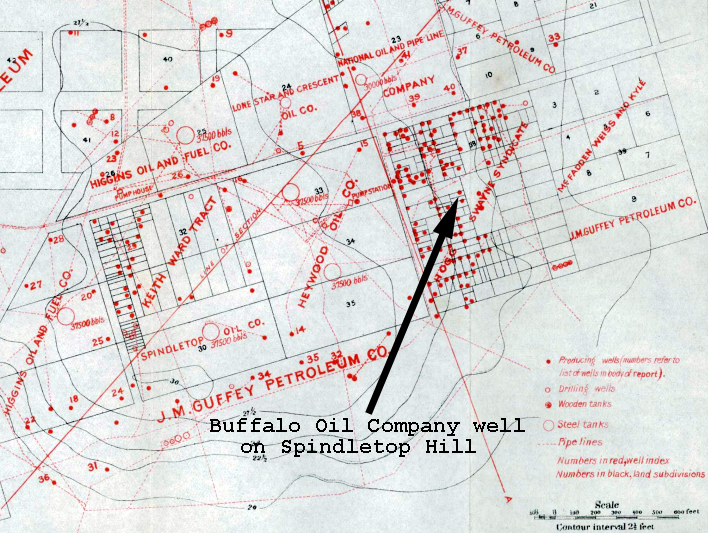

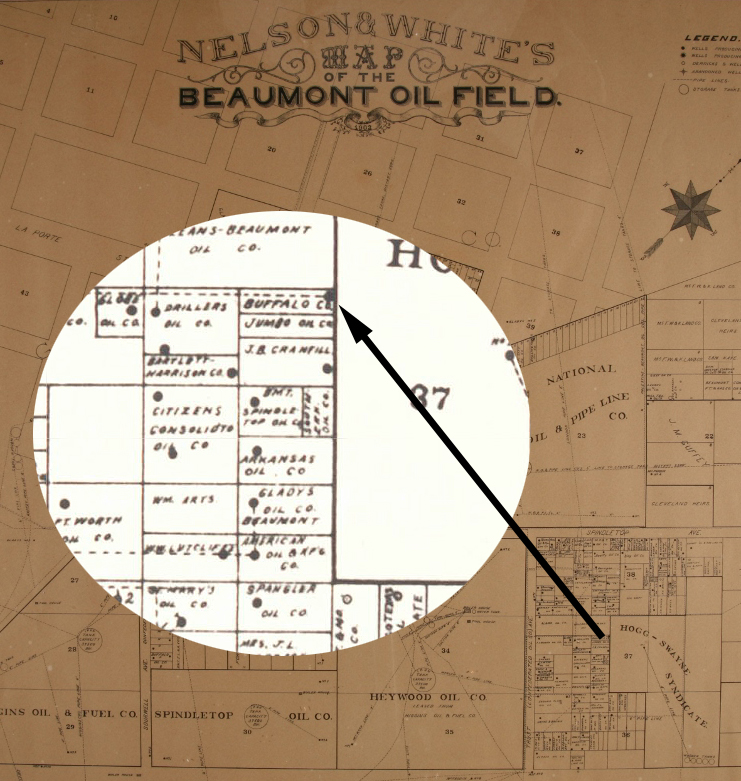

Among the 280 wells at Spindletop in 1902, Buffalo Oil completed a producing oil well at a depth of 960 feet on a lease of only 1/32 of an acre.

Buffalo Oil Company had quickly formed with $300,000 capitalization and stock listed with par value of 10 cents. Encouraged by the first well’s success, speculators invested in the company’s second. But by May 1902 the second Buffalo Oil well was “dry and abandoned” after reaching 1,400 feet deep.

As at least one expert noted at the time, the average life of flowing wells was short, “frequently but a few weeks and rarely more than a few months, with constantly diminishing output.”

Meanwhile, competing companies drove up the cost of drilling equipment and leases. Spindletop Hill was crowded with wooden derricks, oil storage tanks, and roughnecks.

Batson Oiflield

With signs of Spindletop production dropping, Buffalo Oil shifted operations to nearby Batson, where a 1903 well drilled by W.L. Douglas’ Paraffine Oil Company produced 600 barrels of oil a day from a depth of 790 feet. But the exploration company’s luck did not improve.

Map with detail showing Buffalo Oil Company lease among other drilling companies at Beaumont, Texas, home of a giant oilfield discovered in 1901.

As the Batson field reached its peak monthly production of 2.6 million barrels of oil, a fire swept through the crowded oilfield.

“The fire burned furiously for several hours and though there were no fire appliances on the field, it is doubtless if equipment could have been used owing to the intense heat generated by the flames,” noted the Petroleum Review and Mining News.

Buffalo Oil Company’s well, derrick and equipment were completely destroyed.

Often caused by lightening strikes, oil tank fires were sometimes fought using cannons (learn more in Oilfield Artillery fights Fires). After the Batson fire, the annual Buffalo Oil Company stockholder’s meeting took place in April 1904.

Fire engulfed the Batson oilfield in 1902, destroying the equipment and future of Buffalo Oil Company. Photo courtesy Traces of Texas.

“The company states that their recent investment at Batson so far has proved a serious loss to them, and the present outlook is very unfavorable,” reported the Petroleum Review and Mining News. But it got even worse.

Two weeks after the dire report to share owners, a second Batson fire destroyed another Buffalo Oil producing well and two 1,200-barrel storage tanks. Petroleum Review and Mining News concluded the fire “probably originated through an explosion in the pumping plant.”

The Batson oilfield would continue to produce for many years, but without Buffalo Oil Company. As late as 1993 the field yielded almost 200 barrels of oil a day, but Buffalo Oil was history without having paid a dividend.

The stories of many exploration companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery (2008). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2023 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Buffalo Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/buffalo-oil-company. Last Updated: October 31, 2023. Original Published Date: October 28, 2017.