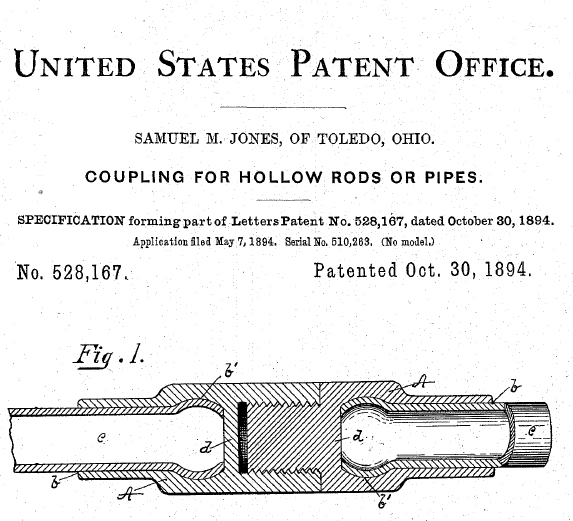

Oilfield service company founder and future mayor of Toledo patented a “Coupling for Pipes or Rods” in 1894.

Samuel “Golden Rule” Jones of Ohio made a fortune in oilfields and supplying equipment and services, patented an improved sucker rod for pumping oil, and created a better workplace for his factory employees. He ran on the progressive Republican ticket in 1897 and was elected mayor of Toledo. He would be reelected three times.

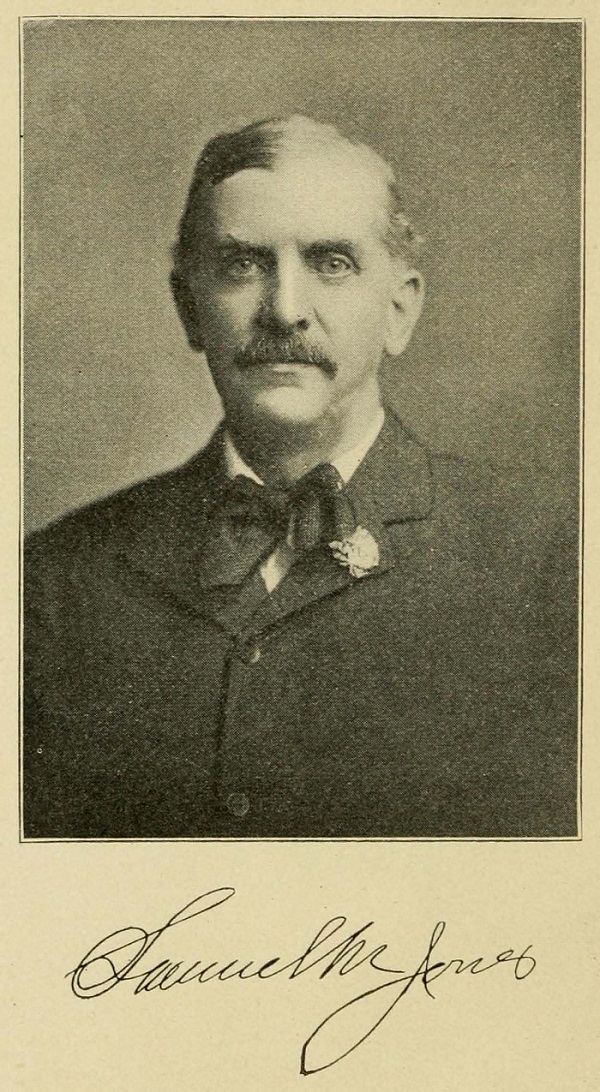

As the country weathered an 1890s financial crisis, Samuel M. Jones brought a new business philosophy to Toledo, Ohio. An immensely popular mayor, he was reelected in 1899, 1901, and 1903 — and served in office until dying on the job in 1904.

Samuel M. Jones photo circa 1904 by Ernest Crosby, courtesy Clarence Darrow Digital Collection, University of Minnesota Law Library.

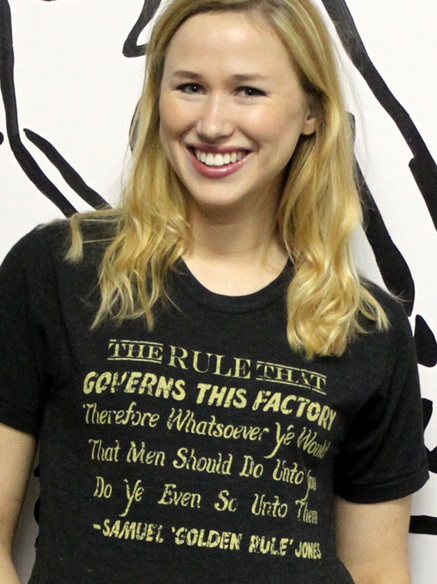

“Golden Rule” Jones, according to one Toledo historian, was the “best known, best liked and best hated mayor of all time who tried to govern a city by the one and only rule by which he governed his factory.” His principle was simple: “Therefore Whatsoever Ye Would That Men Should Do Unto You, Do Ye Even So Unto Them.”

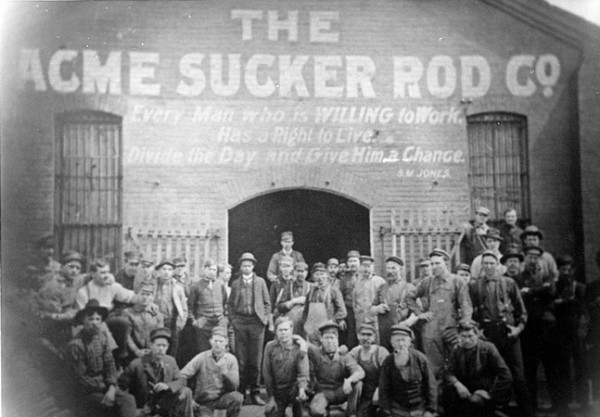

Long before his political career as a progressive reformer, Jones had worked in newly discovered Pennsylvania and Ohio oilfields. He had visited many boom towns, including the infamous Pithole (1865), before returning to Ohio to found the Acme Sucker Rod Company in 1892.

An advocate of eight-hour workdays to increase employment opportunities, Jones introduced higher wages, paid vacations, and five percent bonuses. He earned his nickname “Golden Rule” after posting the biblical admonition for his factory employees.

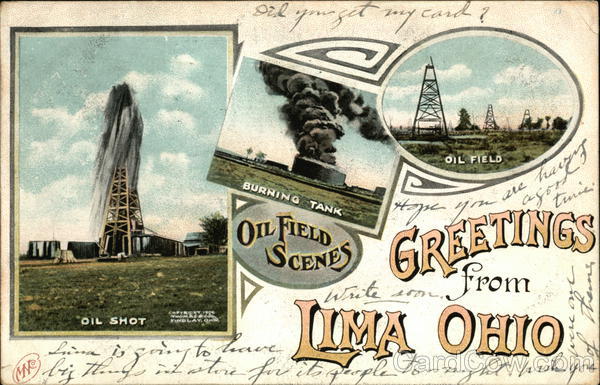

Lima Oilfield Discovery

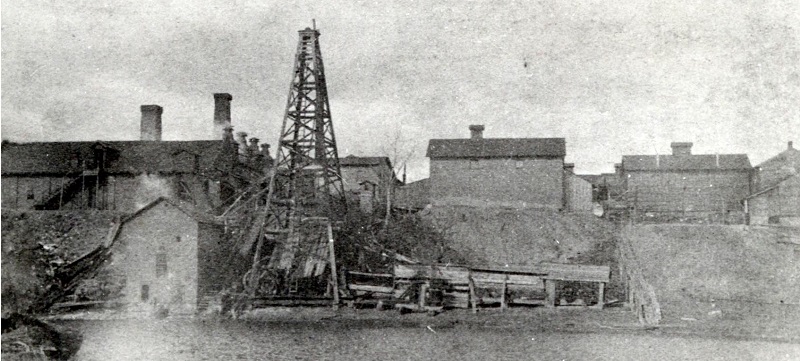

Southwest of Toledo, Ohio’s “Great Oil Boom” had begun on May 19, 1885, when a cable-tool driller looking for natural gas found an oilfield. Benjamin Faurot struck oil after drilling into the Trenton Rock Limestone formation to a depth of about 1,250 feet, according to the Allen County Historical Society

Faurot organized the Trenton Rock Oil Company as other exploration companies began drilling in the Lima oilfield, which stretched from Mercer County north through Wood County in Ohio and westward to Indiana.

Following an 1885 discovery well, a circa 1909 postcard promoted petroleum prosperity in Lima, Ohio.

By 1886, the Lima field was the nation’s leading producer of oil. By the following year it was the most productive worldwide.

“Production from the Ohio portion of the Lima-Indiana field reached its peak in 1896, when more than 20 million barrels were brought out of the ground,” noted the Allen County Historical Society.

“Though short-lived, the oil rush brought an influx of people, pipelines, refineries, and businesses, giving a powerful impetus to the growth of northwest Ohio,” concluded the society (learn more Great Oil Boom of Lima, Ohio).

Benjamin Faurot’s 1885 oil well at the Ottawa River discovered the Lima oilfield after drilling into the Trenton Rock Limestone formation. Photo courtesy the Ohio Historical Society.

Meanwhile, as the nation struggled out of a serious economic depression, the “Panic of 1893,” 47-year-old Samuel Jones returned to Ohio from Pennsylvania oilfields. He established his Toledo sucker rod manufacturing business in an abandoned factory on Segur Avenue.

Jones would be remembered as the Toledo mayor who brought the town a renewed sense of community and reform.

Catching Pennsylvania Oil Fever

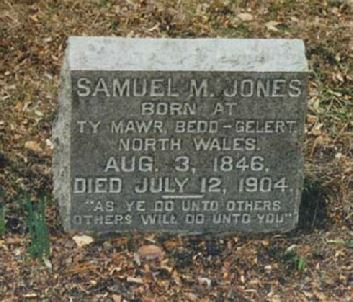

Born in Wales in 1846, Samuel Jones was in Ohio by age 19 and had four years experience as a “greaser and wiper” on the stern-wheeler L.R. Lyon.

Among those who rushed to the Ohio oil boom, Samuel “Golden Rule” Jones founded the Acme Sucker Rod Company in 1892. Photo courtesy Bowling Green State University Archives.

Jones was still a young man when he caught oil fever in 1865. He abandoned his ambition to become a steamboat engineer after his boss told him about Pennsylvania’s booming oilfields not far to the east.

“Sammy, you are a fool to spend your time on these steamboats. You should go to the oil regions,” his boss told him, adding, “You can make $4 a day there.”

Jones followed the advice and his experience with steam boilers eventually landed him a job with the St. Louis & Pithole Petroleum Company — in the notorious Pithole boom town. Discovered in January 1865, the Pithole Creek field created a massive oil boom town for the young petroleum industry, which began in nearby Titusville in August 1859.

Many Civil War veterans wanted jobs, others wanted to make a fortune quickly after having spent long months on army pay. Hundreds of newly organized companies were ready to lease or buy land wherever oil might be found. Pithole became legendary for its wickedness — and for its rapid economic rise and fall.

Jones’ Calvinist upbringing and 12-hour shifts in the oilfield left him little time for the boom town’s debauchery. Jones’ working experience with Pithole’s squalor and desperation left an indelible mark. His empathy for working men remained with him forever.

St. Louis & Pithole Petroleum failed within weeks of Jones being hired and he again found himself looking for work. He spent a year and a half working in northwestern Pennsylvania’s petroleum region as a potboiler, pumper, tool dresser, blacksmith, and pipe layer.

But Jones — like countless others at the time — lost his meager savings when he bought a one-sixteenth interest in a wildcat well that came up dry. Staying in Pennsylvania, Jones eventually settled in Pleasantville, about a dozen miles from Titusville. He spent five years working alongside other oil patch laborers in the Parker’s Landing oilfield.

Finally, a successful $700 investment in western Clarion County oil leases brought Jones a measure of success. By 1878, he was able to secure more good leases in the prolific Bradford field. Jones was 32 years old. Eight years later, he followed new discoveries at Lima, Ohio.

Good Fortune in Oilfields

Jones invested in a Lima oilfield well that produced an initial flow of 700 barrels of oil a day. In the first three months, his well flowed over 14,000 barrels — with Standard Oil buying all production at 40 cents per barrel.

Jones and other independents resisted Standard Oil’s growing monopoly by forming the Ohio Oil Company — today’s Marathon. He became very wealthy when he left the company when Standard took it over two years later. The Panic of 1893 began just before Jones claimed his first patent.

With his “Coupling for Pipes or Rods,” Jones applied his almost 40 years of experience in oil industry mechanics to solve the frequent and time-consuming problem of broken sucker rods, which push and pull a down-hole pump to bring up the oil. The design was a great innovation (also see All Pumped Up — Oilfield Technology).

Prior to patenting his sucker rod design in 1894, Samuel Jones worked in Pennsylvania’s oil regions as a potboiler, pumper, tool dresser, blacksmith, and pipe layer.

The invention would make Jones a millionaire, create jobs, and establish the Acme Sucker Rod Company factory in Toledo.

But as the U.S. financial panic worsened, Jones was appalled by the long lines of unemployed and the threats of dismissal that punctuated many factories “string of rules a yard long.” Alternately labelled as progressive, eccentric, socialist, independent, and anti-capitalist, Jones looked out for workers in an age of big business.

Progressive Employer

Above his factory’s entrance, Jones declared in large letters: “Every Man who is WILLING to work, Has a Right to Live. Divide the Day and Give Him a Chance.” The declaration and his shortening of the work day added to the popular “Golden Rule” reputation of Jones.

“Even more astounding, Mr. Jones developed a revenue-sharing program for his workers, provided health insurance, and subsidized hot meals in the Acme cafeteria,” explained George J. Tanber in a 1999 article for the Toledo Blade.

Unlike other companies, which had a long list of regulations and requirements for their employees, Jones posted only one rule on his company’s notice board, Tanber reported in the article, “City Flourished Under Golden Rule of Jones.”

Next to his sucker rod factory Jones built Golden Rule Park, “where his employees could exercise or relax — and where the employee ensemble, the Golden Rule Band, could entertain.”

Samuel M. Jones (1846-1904) was buried in Toledo’s Woodlawn Cemetery, established in 1876.

Jones’ initiatives soon drew him into the contentious world of late 19th century politics where his belief in reform made him popular. “In time it became clear that Mr. Jones was using Acme as a model for social change, and that he would soon apply his method to city politics,” Tanber explained in the newspaper article.

In 1897, Jones received the Republican party’s nomination for Toledo mayor. Two years later, Republican leadership refused to nominate him again, but Jones still ran and easily won reelection with 70 percent of the vote.

Samuel Milton Jones remained a reformer until his last day on the job in 1904, when he died at age 58. Five thousand people attended his funeral. Jones’ biographers have noted his early years in tough oil boom towns influenced both his business practices and his philosophy in politics.

Jones once observed that most manufacturers kept about $8 out of every $10 their employees earned for them. “I keep only about seven and so they call me ‘Golden Rule’ Jones,” he said.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Holy Toledo: Religion and Politics in the Life of “Golden Rule” Jones (1998); Ohio Oil and Gas, Images of America

(2008). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Golden Rule” Jones of Ohio. Authors: B.A. Wells and K. L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/golden-rule-jones-of-ohio. Last Updated: October 22, 2024. Original Published Date: May 24, 2014.