Crayola — a 1903 petroleum product name combining the French words craie, chalk, and oléagineux, containing oil.

Many petroleum products hide in plain sight. For Pennsylvania’s Benny & Smith Company, common oilfield paraffin changed the company’s future by coloring children’s imaginations. Before inventing Crayola crayons, the partners patented a “dustless chalk,” a red oxide paint, and Staonal — “stay-on-all” — the blackest of black markers.

Three decades after America’s first oil well at Titusville, Pennsylvania, Crayola crayons began with an 1881 refining patent by Edwin Binney to make carbon black, an intensely black pigment. Binney and partner C. Harold Smith had launched their company in Easton to sell inks, black polishes, and chalk for schoolroom blackboards.

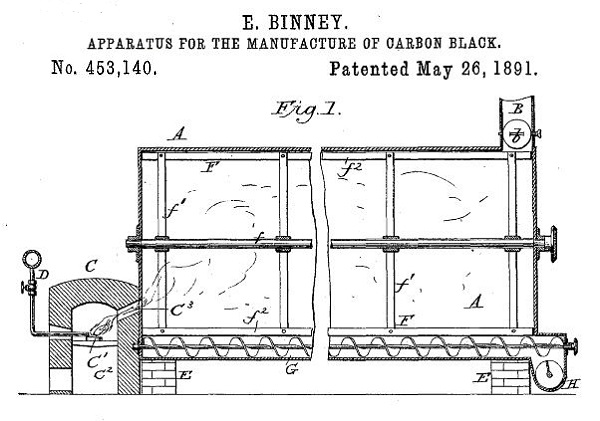

Binney & Smith Company received an 1891 patent for an “Apparatus for the Manufacture of Carbon Black,” which produced a fine, soot-like black pigment — far better than any other in use.

Pennsylvania’s booming oilfields would prove key to success, beginning with using natural gas in a patented “Apparatus for the Manufacture of Carbon Black.” Binney & Smith Company later would add oilfield paraffin — the bane of oil producers since it clogged wells — and mix in colors to create a petroleum product named Crayola.

Manufacturing Carbon Black

On May 28, 1891, Binney received a patent for the company’s method to efficiently produce a fine, soot-like substance more intensely black than any other pigment in use at the time.

“The objects of my invention are to manufacture lamp-black from oil in an improved and economical manner, whereby waste of the product and unnecessary expenditure of labor are avoided,” Binney noted in his patent application.

His patent (No. 453,140) proclaimed a process to “manufacture carbon-black from gas in such a manner as to obtain improved quality of black which shall have the soft flaky texture of lamp-black made in ordinary ways.”

A fifth-grader’s skillful use of crayons illustrates oil production. Image courtesy Pioneer Oil Museum of New York, Bolivar.

The young U.S. petroleum industry, rapidly expanding its refineries to fuel kerosene for lamps, supplied Binney & Smith with oil and natural gas feedstock for the company’s carbon black. Revolving metal drums cooled the heat and smoke directed from the burning gas.

“Stay on All”

The company’s refining process produced a fine, soot-like substance of incredible blackness — a better pigment than any other. Binney & Smith’s carbon black received an award at the 1900 Paris Exposition, a world’s fair of the century’s achievements.

Meanwhile, the Pennsylvania inventors mixed their carbon black product with oilfield paraffin and other waxes to introduce a paper-wrapped black crayon marker for crates and barrels. The company promoted the marker as being able to “stay on all” and accordingly named “Staonal.”

Resulting from an 1891 carbon black patent, Binney & Smith added oilfield paraffin to produce a black marker. Staonal is still sold.

Staonal became a highly successful company product, but the concentrated carbon black content precluded its use by children. The company earlier had found great success manufacturing “dustless chalk” for schoolrooms and red iron oxide for a red paint for barns.

Classroom Chalk

Although they longed for color, students in Alice Stead Binney’s classroom had to settle for dustless chalk. In fact, An-Du-Septic dustless chalk proved so popular among turn-of-the-century teachers that it won a Gold Medal at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis.

Teachers like Alice loved the tidy new product, but their choices were limited. Pencils of the day were primitive, with square “leads” made from a variety of clays, slates, and graphite. Color writing implements were the toxic and expensive imports of artists, best kept away from schoolchildren.

Experiments in 1902 produced An-Du-Septic, a white dustless chalk soon popular with teachers. Photo courtesy Benny and Smith Company.

Alice’s husband Edwin, and his cousin, C. Harold Smith, created An-Du-Septic chalk as a consequence of expanding their pigment business into the sideline production of slate pencils for schools.

In Easton, the Binney & Smith Company, formerly the Peekskill Chemical Works, made its reputation by producing a red iron oxide for paint and carbon black for paints, inks, and iron stoves. Binney & Smith also produced shoe polishes. School teachers and their students would bring change.

Slate pencils and the very successful An-Du-Septic dustless chalk put Binney & Smith salesmen into America’s classrooms. The company’s sales force listened to teachers and learned there would be a ready market for inexpensive, non-toxic, brightly colored crayons.

“Crayola” from Oilfield Paraffin

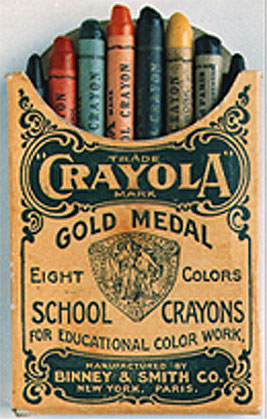

In 1903, Binney & Smith launched a colorful product that would forever change childhoods. Alice Binney provided the name by combining the French word for chalk, craie, with the Old French word oléagineux — meaning something that contains oil.

The manufacturing process began with mixing small batches of carefully measured and hand-mixed pigments, paraffin, talc and other waxes. Employees individually rolled paper labels and pasted them onto each crayon by hand.

Identically packed into small boxes, thousands easily could be shipped in wooden crates. Sixteen Crayola crayons sold for 10 cents; eight for 5 cents: red, yellow, orange, green, blue, violet, black, and brown. Crayola became an instant hit.

Binney and Smith produced the first box of eight Crayola crayons in 1903 — red, orange, yellow, green, blue, violet, brown, and black.

The company’s proprietary formulas have remained a closely guarded secret as demand for its crayons has grown worldwide. Production capacity reportedly is more than four million crayons every day, thanks to oilfield paraffin from distant petroleum refineries delivered to Crayola’s Easton factory in railroad tank cars.

In January 2007, Binney & Smith became Crayola LLC in recognition of the company’s number one brand. The company is now known as Crayola. Crayola has grown to become a $500 million a year business — a successful union of the petroleum industry to the colorful world of children’s imaginations.

“This organizational and name change showcases the company’s Crayola brand, sold by Binney & Smith since 1903,” explained the company, which also opened a museum in Easton. Crayola is sold in more than 80 countries, “and represents innovation, fun, kids and quality.”

As paraffin continued to find its way into products (see The Crude History of Mabel’s Eyelashes), manufacturers in 1912 for the first time added Binney & Smith’s carbon black to tires. Until the addition of carbon black to improve durability, auto tires were white.

Carbon Black Hits the Road

In 1839, bankrupt Philadelphia hardware merchant and erstwhile inventor Charles Goodyear accidentally dropped rubber and sulfur on a hot stovetop. The rubber charred like leather yet remained elastic, a discovery that led to “vulcanization.”

During the new process, natural rubber could be transformed into an industrial product with innumerable uses. Goodyear’s famous lawyer, Daniel Webster, praised his client’s invention. “It introduces quite a new material into the manufacture of the arts, that material being nothing less than elastic metal,” Webster proclaimed.

Automobile tires were the ideal application for this new product. Between 1895 and 1905, more than 77,000 new automobiles were registered in the United States (See Cantankerous Combustion — First U.S. Auto Show).

The tires of this 1904 Oldsmobile Model N Touring Runabout were not chosen for their color. Until B.F. Goodrich introduced “carbon black” into the vulcanizing process in 1910, auto tires were white.

Natural rubber pigments and zinc oxide used in the manufacturing process gave tires their while color. At the time, most cities had a downtown maximum speed limit of 10 mph.

In 1910, the B.F. Goodrich Company found that adding carbon black to the vulcanizing process dramatically improved strength and durability. The material came from controlled combustion of both oil and natural gas. Its use in tires created an immense market — initially consuming one pound of carbon black for every two pounds of rubber.

Correspondingly, as America’s automobile industry grew, so did demand for tires and carbon black. By 1931, Texas annually produced more than 200 million pounds of carbon black from just 31 plants — about 75 percent of America’s total production.

Today, most of America’s carbon black is still produced in Texas and Louisiana. Demand remains closely associated with auto tires. Cabot Corporation — founded in Pennsylvania in 1882 — is the largest U.S. producer of the intensely black petroleum product. By 2024, the company operated 43 manufacturing facilities in more than 20 countries.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Crayola Creators: Edward Binney and C. Harold Smith, Toy Trailblazers (2016); Carbon Black, Its Manufacture, Properties, and Uses (2018); The B.F. Goodrich Story Of Creative Enterprise 1870-1952

(2010). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an annual AOGHS supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “’Carbon Black & Oilfield Crayons.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/products/oilfield-paraffin. Last Updated: May 22, 2025. Original Published Date: September 1, 2007.