Horrific East Texas oilfield tragedy of 1937.

At 3:17 p.m. on March 18, 1937, with just minutes left in the school day and more than 500 students and teachers inside the building, a massive explosion leveled most of what had been the wealthiest rural school in the nation.

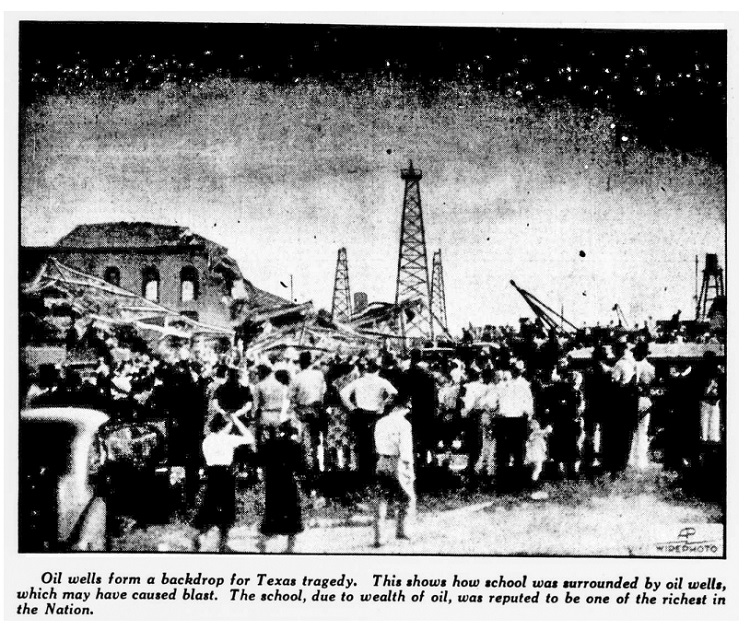

Hundreds died at New London High School in Rusk County after odorless natural gas leaked into the basement and ignited. The sound of the explosion was heard four miles away. Parents, many of them roughnecks from the East Texas oilfield, rushed to the school.

Despite immediate rescue efforts, 298 died, most from grades 5 to 11 (dozens more later died of injuries). After an investigation, the cause of the school explosion was found to be an electric wood-shop sander that sparked the residue gas vapors (also called casinghead gas) that had pooled beneath and in the walls of the school.

Roughnecks from the East Texas oilfield rushed to New London school after the March 18, 1937, explosion — and searched for survivors throughout the night. Photo courtesy New London Museum.

“The school was newly built in the 1930s for close to $1 million and, from its inception, bought natural gas from Union Gas to supply its energy needs,” noted History.com. “The school’s natural gas bill averaged about $300 a month.”

In early 1937, the school board canceled its contract with Union Gas to save money and tapped into a pipeline of casinghead gas from Parade Gasoline Company, according to historian James Cornell.

“This practice — while not explicitly authorized by local oil companies — was widespread in the area,” he reported in The Great International Disaster Book. “The natural gas extracted with the oil was considered a waste product and was flared off.”

Natural gas produced from the top of an oil well — the casinghead — contains either dissolved or associated gas or both. The residue gas collects in the annular space between the casing and tubing in the oil well before separating during or shortly after production and flared for safety.

In early 20th century, processing plants began turning oilfield associated gas into a low quality but inexpensive gasoline of between 40 octane and 60 octane. The product was called white gas, condensation gasoline, and natural gasoline.

The disaster made headlines from Alaska Territory to Washington, D.C., where President Franklin D. Roosevelt enlisted the Red Cross and government agencies to send assistance. Image courtesy The Evening Star, Washington D.C., March 19, 1937.

By 1920, Oklahoma had 315 casinghead gas plants in operation, including the first built west of the Mississippi River (see Casinghead Gasoline at Glenn Pool). But the hazards of vapors from casinghead gas had been exposed on September 27, 1915, when a railroad car carrying casinghead gasoline exploded in downtown Ardmore, killing 43 people and injuring others.

Cronkite reaches the Scene

A young journalist working for United Press in Dallas, Walter Cronkite, was among the first reporters to reach the scene of the disaster south of Kilgore, between Tyler and Longview. It was dark and raining in East Texas.

“He got his first inkling of how bad the incident was when he saw a large number of cars lined up outside the funeral home in Tyler,” noted a local historian. Floodlights cast long shadows at the site of the disaster.

“We hurried on to New London,” Cronkite wrote in his book, A Reporter’s Life. “We reached it just at dusk. Huge floodlights from the oilfields illuminated a great pile of rubble at which men and women tore with their bare hands. Many were workers from the oilfields.”

The March 18, 1937, explosion hurled a concrete slab 200 feet onto a new Chevrolet. Students had been preparing for the next day’s Inter-scholastic meet in Henderson. Photos courtesy New London Museum.

Decades later, the retired CBS Evening News anchor added, “I did nothing in my studies nor in my life to prepare me for a story of the magnitude of that New London tragedy, nor has any story since that awful day equaled it.”

A Bad Decision

David M. Brown, who researched the tragedy for a 2012 book, described the “sad irony” of how the East Texas oil boom financed building the wealthiest rural school in the nation in 1934 — and the faulty heating system that permitted raw gas to accumulate beneath it.

According to Brown, the explosion was partly the result of school officials making a bad decision.

To save money on heating the school building, the trustees had authorized workers to tap into a pipeline carrying “waste” natural gas produced by a gasoline refinery. The resulting explosion laid waste to a town’s future, Brown concluded in his book Gone at 3:17, the Untold Story of the Worst School Disaster in American History.

The New London Museum includes extensive personal accounts of the tragedy taken from newspaper articles and personal interviews.

Following the disaster, a temporary morgue was set up near the school as well as nearby Overton and Henderson, noted Robert Hilliard, a volunteer for the New London Museum.

“Many burials were made in the local Pleasant Hill cemetery that to this day, still symbolize the great loss that families endured, added Hilliard, among those who have maintained the museum’s website. “Many of the grave sites display porcelain pictures of the victims,” he said. “Marbles that were once played with were pushed into the cement border outlining the graves.”

Making Natural Gas Safer

As a result of the disaster, Texas was the first state to pass laws requiring that natural gas be mixed with a “malodorant” to give early warning of a gas leak. Other states quickly followed. The now mandated rotten-egg smell associated with natural gas is Mercaptan, the odorant added to indicate the potentially dangerous leaking of gas.

The London School campus for grades 5 through 11, “was a new showplace in 1937, the product of new oil wealth that could not have been imagined 10 years earlier,” according to the New London Museum.

New London’s community museum, across the highway from the school site, began in 1992 thanks to years of work by its founder and first curator, Mollie Ward, who was 10 when she survived the devastating explosion. She said in a 2001 interview that among the museum’s exhibits was a blackboard found in the rubble.

“Sometime in the night a worker found a blackboard that had been on the wall that read ‘Oil and natural gas are East Texas’ greatest mineral blessing,'” said Ward, who spent years helping start a former students association that reunited survivors of the New London explosion.

One museum exhibit is a recovered blackboard that reads: “Oil and natural gas are East Texas’ greatest mineral blessing.” Photo by Bruce Wells.

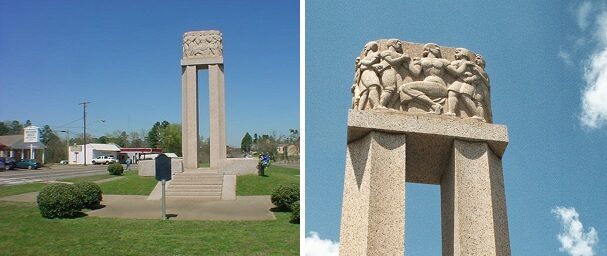

Near the museum is a 32-foot-high granite cenotaph dedicated in 1939. In December 1938, a contract for building a monument was awarded to the Premier Granite Quarries of Llano, Texas, with Donald Nelson of Dallas supervising architect for the project.

After a competition between seven Texas sculptors who submitted preliminary designs, Herring Coe of Beaumont created the model for the sculptural block at the cenotaph’s top.

Near the New London museum stands a 32-foot granite cenotaph dedicated in 1939. Life-size figures represent children coming to school, bringing gifts and handing in homework.

The 20-ton sculptured block of Texas granite — supported by two monolithic granite columns — depicts 12 life-size figures to represent children coming to school, bringing gifts and handing in homework to two teachers.

The March 18, 1937, East Texas tragedy and those who died are remembered at the New London Museum.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Gone at 3:17, the Untold Story of the Worst School Disaster in American History (2012); A Texas Tragedy: The New London School Explosion (2012); The Great International Disaster Book (1976); A Reporter’s Life (1997). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2024 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “New London School Explosion.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/new-london-texas-school-explosion. Last Updated: May 8, 2024. Original Published Date: March 11, 2011.